Does Posture Matter?

A detailed guide to posture and postural correction strategies (especially why none of it matters very much)

Many health-conscious people are haunted by the idea that they “should” correct their posture. They fight a long-term, tedious war against self-imposed or careless crookedness, assuming it’s essential self-defense against common problems like neck pain, headaches, and especially low back pain. Is it all a wild goose chase? Are aches and pains caused by “poor posture” in the first place? Even if they are, is it actually possible to improve posture?

The ways that we sit and stand and walk are among the strongest of all habits. Changing posture may be as hard as quitting smoking or potato chips. So it had better be worth the effort!

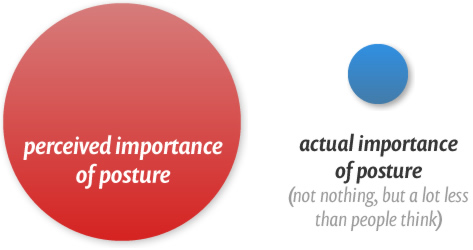

After working as a massage therapist for many years,1 I became confident that poor posture is a “real” thing,2 a legit source of partially preventable physical stress and therefore probably a factor in chronic pain, mostly later in life. But this posture stuff is deceptive. There may be "something to it," but there is definitely not a lot to it. There aren’t many easy wins for people here. And there is plenty of potential to waste time and money — or even get hurt.3

Delving deeper into the topic as a journalist — much deeper than I ever did as a massage therapist, studying the scientific literature and learning more from countless readers and experts — I have developed many doubts about posture’s importance and the value of trying to change it. I have come to believe that many healthcare professionals pathologize posture, exaggerating its importance to justify costly therapy — all with good intentions, of course. Our love affair with posture is the most obvious and embarrassing example of “structuralism”: an excessive and simplistic focus on the role of biomechanics and symmetry in how pain and injury work.4

This doorstopper of an article (a small book really) thoroughly explores strategies for postural improvement that may be helpful, but I also explain why the idea of “poor posture” is mostly much ado about nothing — a problem in theory, but only a minor one in practice. If your main issue is stubborn aches and pains, there are probably much better ways to spend your time than trying to improve your posture.

“I don’t always have good posture in front of my PC. But when I do, it’s because I just read about good posture.” ~ The Most Interesting Man In the World (meme image not shown because copyright)

What is posture?

Posture is not a position, but a constantly shifting pattern of reflexes, habits, and adaptive responses to anything that challenges your ability to stay upright and functional, such as:

- Gravity, of course!

- Awkward working conditions, which may be unavoidable (nurses must lift patients!), and/or self-inflicted and correctable (lousy ergonomics).

- Abnormal anatomy.

- Athletic challenges.

If you start to tip over, or lose the stability you need for a task, postural reflexes kick in and engage muscles to pull you into a more or less upright and/or functional position again. The biological systems and tricks that keep us upright are nifty, and surprisingly poorly understood.5

Posture is the embodiment of your comfort zone. At worst, it can be like a cage.

Posture is also body more than the sum of those parts, more than “just” a collection of righting and stabilizing reflexes — it is the way you live, the shape of your flexible “container,” a physical manifestation of your comfort zone. We habitually hold ourselves and move in ways that serve social and emotional needs, or avoid clashing with them. It is a major part of body language. Posture can be submissive or dominant, happy or sad, brave or fearful, apathetic or uptight.

The challenges and rewards of trying to change posture are not just musculoskeletal: it can be a profound personal process. Patterns and behaviours that lead to trouble are usually strong.6 This article does not get too “deep” and mostly sticks to the musculoskeletal issues and the relationship between posture and pain, but the psychology of posture also matters.

What poor posture is not: Upper-Crossed Syndrome (and its ilk)

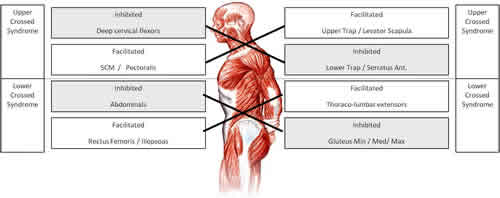

One of the best-known specific examples of allegedly poor posture is “Upper-Crossed Syndrome” (UCS). It sounds impressively technical. Named by a Czech doctor and researcher, Vladimir Janda, it is the apex of clinical storytelling about posture in therapy culture, and the prototypical “muscle imbalance” theory. No idea about bad posture has ever been both this popular and “advanced.” It is the backbone of conventional wisdom about posture. And what is it?

Basically just slouching.

Head and shoulders forward, mostly, but UCS comes with some complicated assumptions about its causes and consequences, like your muscles dysfunctional ship’s rigging: some are weak and loose (“inhibited”), while others are too strong and tight (“facilitated”). Viewed from the side, you can draw diagonal lines between these groups that cross. (There’s a Lower-Crossed Syndrome as well, but it’s much less famous.)

Dr. Janda was a pioneer. He did good work with the information he had at the time. But he was probably mostly wrong about UCS,7 and the rest of the article substantiates this in many ways. But here’s one quick, fresh, solid example…

A good quality 2021 study of hundreds of young folks showed that they actually got less neck pain over five years if they had a classic UCS posture.8 Less! It was good for them. Conversely, an erect posture was linked to more neck pain. The difference wasn’t huge, but it was a difference in exactly the wrong direction for validating Dr. Janda’s idea. (There’s a modest assortment of other studies of UCS, but all of them focussed on whether or not it is possible to change it, and not on whether or not it actually needs to be changed: that is always just embraced as a key premise.)

Muscle imbalance ideas in the same class as UCS have not done well over the last couple decades. Jason Silvernail, Doctor of Physical Therapy, comments: “There is almost no data to support these ideas and to my knowledge there never has been.” For instance, another famous one: “hamstring-to-quadriceps (H:Q) strength ratio.” The idea is that the quads and hamstrings need to be equally strong, responsive, flexible, and so on. This has been the focus of uncountable millions of training hours… but after decades, the science hasn’t really advanced. A 2022 review was conclusively inconclusive: we still basically have no idea if it’s true, and it’s unlikely.9 But that hasn’t stopped generations of physical therapists and coaches from prescribing exercises to “fix” your H:Q ratio.

And if you think that science is weak, you should see the science of glutes that allegedly don’t "fire" when they should. 🙄

Things like inhibition and facilitation sound technical and specific, but they aren’t: they are pseudo-jargon, words for things that are actually poorly understood and defined. Research has relentlessly shown that professionals have trouble agreeing on muscle balance. The “tightness” of muscles doesn’t seem to have much to do with their strength, or with pain, or really anything that anyone can actually work with. If certain muscles were actually weak in everyone exhibiting a certain posture, and those people tended to have certain problems, then it would make sense to try to strengthen those muscles specifically. But they aren’t, and they don’t, so it doesn’t. Treating people as if they have UCS — with targeted stretching, strengthening, and massage, say — doesn’t work any better than generally getting more exercise.

Nor is any of this surprising given where the science has gone. It has become clear that the “behaviour” and condition of individual muscles is mostly trivial compared to the potent role of the central nervous system as the dictator of almost everything about both function and sensation. In short, it’s not messy muscle function that makes people slump and hurt — it’s a brain thing, and UCS is an effect instead of a cause.

Or UCS is just a clinical fantasy: it’s most likely that there just isn’t a UCS pattern at all, no “cross” of weak/tight muscles. A bogus narrative. There is just a common posture, plus the panoply of human aches and pains that come and go like aurora borealis, most of which still cannot be specifically explained and probably never will be. The fundamental problems of troubleshooting chronic pain is that there are so many possible causes and chronic pain isn’t a reliable, informative signal.

UCS is just a good story Dr. Janda told in the absence of good data. It seemed like a good idea at the time, but it has become quite obsolete. So why is this vision of poor posture still so popular? Jason Silvernail again:

“It’s accessible to a wide variety of practitioners. Since it involves muscular assessment, everyone from physicians to personal trainers to physical therapists, chiropractors, athletic trainers, massage therapists and strength coaches could use this approach with their patients or clients. Both clinicians (physicians, physical therapists, chiropractors, athletic trainers) and fitness and service professionals (personal trainers, strength coaches, massage therapists). Those with rigorous academic education at doctoral or postgraduate level (physicians, physical therapists), those with college education (athletic trainers, strength coaches, some trainers) and those with trade school or certification training (personal trainers, massage therapists). Huge numbers of different people in different fields could use this. A marketing dream. It provides a simple solution to a complex problem that leverages deeply embedded cultural ideas that are far more powerful than scientific data.

“That’s why these crossed syndrome type things make no sense whatsoever but are not going away any time soon. People will be talking about this brilliant insight for another 50-odd years. I wonder if Janda would [facepalm] if he heard how people were unable to move beyond this idea, and had more fidelity to this particular product/idea than to the process he advocated.”

This is what skeptics mean when they say that there is no such thing as bad posture — and I completely agree with the spirit of that position. But there is also more to “poor posture” than UCS. Or perhaps I should say there’s less to it …

What is “poor” posture?

My definition of poor posture is simple (but took me many tries to settle on):

Poor posture is any habitual, self-imposed positioning that causes physical stress, especially coping poorly with postural challenges.

A postural challenge is anything that makes it harder to maintain a comfortable posture, such as “work.” A major source of postural challenges in all our lives is awkward tool use, also known as crappy ergonomics.

Sitting for hours with your knees tucked sharply under your chair is a good basic example of a poor posture. No one has to sit like that. The chair isn’t forcing it. It’s an entirely optional arrangement of limbs. And yet it is an actual hazard to kneecaps10 — a completely avoidable hazard, which most people fail to avoid because they just don’t know how knees work.

If anyone ever tells you there’s no such thing as poor posture — a popular skeptical perspective — that example is a fine rebuttal. And there are certainly others.11 How much poor posture actually matters on average — not very much, probably — but for sure there is such a thing.

Postural laziness

What about postural laziness? Specifically what most people actually mean when they think of poor posture, thanks to the Puritans,12 is slouching: a lazy, sloppy posture. The negative connotation is standard: it’s not a “relaxed” and “carefree” posture! The avoidance of postural challenges leads over time to poor postural fitness. In other words, if you avoid postural challenges enough, eventually you’ll have trouble coping with them when you have to … and so we’re back to the first definition.

Comic by MimiAndEunice.com, which is a lovely place.

Other than “laziness,” why would anyone respond ineffectively to life’s postural challenges? Weakness, mood, pain, hang-ups, fatigue, fear, stress … and more (as if that wasn’t enough).

Sometimes an effective response to a postural challenge is almost impossible, and that really gets you off the poor posture hook. Many seemingly poor postures are actually just compromises, adaptations to unavoidable stresses. Posture zealots forget this. If the cause of a posture is baked into your anatomy, trying to change it is going to hurt more than help, or it will just be futile. If your posture is caused by adaptation to a shortened leg bone dating back to a motorcycle accident twenty years ago, you aren’t going to have much success changing your posture. The context of posture is important! As often as not, what seems like a poor posture is just a functional adaptation, and sneering at it is ridiculous.

For instance, an old man may walk stooped over because he has spinal stenosis and it really hurts to stand up straight. There’s nothing lazy about his stooping. The stooping is creating postural stress, but it’s the lesser of two evils, and it’s the same postural compromise that everyone with painful stenosis chooses. But for a young man, presumably without stenotic back pain, the same posture would be really strange: an unnecessary stress, certainly “poor” and worth fixing, if possible.

Of course, for the most part young men do not stoop like old men …

Daniel watched Isaac gain a couple of inches in height as he remembered the erect posture that Puritans used to set a better example.

a fictionalized Isaac Newton and his Cambridge roommate, Daniel, in Quicksilver, by Neal Stephenson

Does posture matter?

Physical therapists certainly think that posture matters. In a 2019 survey, several hundred of them were asked to rate the importance of optimal sitting and standing posture, and 65% considered it “very” important (and another 28% ranked it just below that).13 They did not entirely agree on what those postures are, which is a bit embarrassing, but they gave similar justifications for them regardless, which is even more embarrassing.

These professional opinions do not appear to be evidence-based.

People probably naturally avoid the most ineffective responses to most significant postural challenges. Homo sapiens is allergic to physical stress. We prefer to be comfy. And although postural laziness might seem obviously evil,14 people also naturally tend to keep up their postural fitness for the things they care about (if you like playing sports, you play them).

The “problem” of poor posture is mostly minor and self-limiting. The worst problems are avoided naturally, instinctively. The postural fitness that matters the most is taken care of almost automatically … and what remains is relatively trivial.

Doing it the hard way!

How long do you think you could work like this without regretting it?

That said, we can also be surprisingly self-defeating! In fact, this seems to be a weird feature of “higher” intelligence:15 we are prone to doing things the hard way and failing to avoid unnecessary stresses. So we probably do make some postural mistakes and develop bad habits, because we are careless, or because our big brains place too much emphasis other priorities, or because don’t even know that we’re doing something stressful (like the knees-tucked-under-the-chair example). Fortunately, the scientific evidence strongly suggests that doing things “the hard way,” posturally speaking, is probably not all that harmful even when we do make that mistake. Some interesting examples …

- A leg length difference is portrayed by many therapists, especially chiropractors and massage therapists, as a serious postural problem that inevitably causes pain. And yet it’s been proven that people with significant leg length differences suffer from no more back pain than anyone else.16 (Not that minor differences can even be reliably diagnosed in the first place.17)

- Athletes with large differences in the mass of their low back and hip muscles — exactly the kind of “imbalance” that is targeted for repair by therapists everywhere — don’t actually get hurt any more often than players with more evenly distributed muscle mass.18

- Or consider this study of coordination exercises for the neck: it showed that the exercises had exactly the intended effect on coordination and posture … but no effect on neck pain at all.19 What’s the point of posture exercise if it doesn’t actually help with pain problems? Maybe none! That’s the point.

All of this flies in the face of “posturology”

Posturology is the cheesy, popular term for the mostly made-up “discipline” of studying the relationship between posture and pain, and even between posture and diseases.20 Posturologists (I can barely type that word with a straight face) tend to assume their own conclusion: they assume that poor posture causes pain, and then look for confirmation of that. And so there are many, many scientific papers that seem to present evidence of a connection between posture and pain, but most of them suck — here’s a nice appalling example21 — and “posturology” is mostly a pseudoscientific research backwater. If posturology research was better quality, we might actually learn something from it. But most of it must be chucked or, at best, taken with a huge grain of salt.

Posture is only one of many hypothetical factors that contribute to pain problems, but in many cases it probably isn’t contributing at all. This is obvious from a simple observation: there are a lot of people with nice posture who are in terrible pain, and also many people with lousy posture but no pain.

The most stereotypical poor posture of them all — a hunched upper back, with the shoulders rolled forward — is widely assumed to be a cause of shoulder and back pain … but the assumption is almost certainly wrong. This has been studied to death (for a posture problem). According to the collective results of ten different experiments it is almost certainly not a cause of shoulder pain.22 A large 1994 study of kyphosis in older women found no connection either: not even the 10% with the worst kyphosis had “substantial chronic back pain, disability, or poor health.”23 There’s just nothing there. Hunchers are not wrecking their shoulders and backs.

More exotically, I had a truly scoliotic patient, an elderly woman with a blatant S-curve in her spine that she has had since she was a child. Despite this obvious major source of postural stress, she suffered nothing worse than annoying back stiffness in her whole life. Another much younger woman, but with extreme scoliosis, was also amazingly pain-free.24 Meanwhile, in my ten-year career as a massage therapist, I had a steady stream of people through my office with severe back pain … and perfectly ordinary posture. What’s the difference between these patients? Probably not their posture.

Research has shown that abnormal curvature of the cervical spine is actually not closely associated with neck pain.

Another good example: a client with a pronounced torticollis (“wry neck”), and who was even little deformed by it.25 But, once again, this middle-aged patient suffers from no more than irritating chronic discomfort, while many people with much more normal head posture are just about driven nuts by neck pain (including yours truly, which is why I wrote a book about neck pain).

There are many better-documented stories like this, like the case of a serious traumatic cervical dislocation reported in New England Journal of Medicine in 2010, notable for being mostly asymptomatic: just torticollis and stiffness, but no pain, weakness, or altered sensation. That such a serious injury could ever have that little impact on a person is quite interesting, and it puts the hazard of “poor posture” in some perspective.26 Research has shown that abnormal curvature of the cervical spine is not closely associated with neck pain27 and is probably not clinically significant.28

“Text neck” and growing “horns”

A large 2016 study of 1100 Australian teenagers showed that there was no correlation — none at all — between their neck posture and neck pain, contrary to all the fear-mongering we’ve heard about “text neck” in the last couple years.29 A similar 2018 study of Brazilian youths came to the same conclusion.30 For balance, I’ll acknowledge there are studies that say otherwise31 … but mostly just crappy studies in my opinion,32 and regardless they do not remotely prove that abnormal curvature actually causes pain.33

In 2019, there was another text-neck-adjacent kerfuffle: a truly bad study, in a pay-to-publish journal, by a chiropractor who sells posture correction gadgets, went viral with the claim that cell phone usage is causing people to grow horns on the backs of their heads.34 Those darn millenials are staring down at their new-fangled “phones” so much that the postural strain on the backs of their heads is causing them to grow “horns” (bones spurs). Kids these days! This is pure junk science, but it’s junk science that got beamed into a kajillion eyeballs. I don’t think such blatant pseudoscience deserves much attention, but if you want to know a little more, that footnote is quite detailed. (I worked hard on it. C’mon … click it! You know you wanna.)

These are the “horns” of study from Shahar and Sayers, allegedly linked to cell phone usage. The implication that the text-neck posture is harmful is completely unsubstantiated and highly implausible. If staring at phones is a problem, it cannot possibly be a new problem: human beings are not remotely new to hunching over their work for hours at a time, and if cell phone usage can cause “horns,” then the sweat shop workers of the 1800s would have grown antlers.

The low back

The story is the same for the low back — the other posture hot zone. It’s all hype and fear-mongering and no persuasive data. For instance, you could hardly ask for a more clichéd notion about posture than the idea that slouching is bad for your back. Teens slouch a lot, and they do get back pain (though much less than adults do), so if posture is an important factor in back pain, it shouldn’t be too hard to find a connection. But a biggish 2011 study did not: “a greater degree of slump in sitting was only weakly associated with adolescent back pain.”35 No smoking gun there.

Good luck even measuring or judging lumbar curvature. A nifty little 2020 experiment showed clearly that it changes practically every time you stand up. Spinal shape is very dynamic, and typical postural assessment methods are highly unreliable.36

Physical therapists tend to make too much fuss over extremely subtle postural “problems,” which match up even more poorly with pain than the obvious postural problems.37 The popularity of such theories generally suggests to me that posture is often a therapeutic red herring. Both its importance and its “fixability” are routinely overestimated by professionals in a self-serving way.

And yet that doesn’t mean there isn’t still something of interest going on. Health problems don’t have to be severe to be of interest.

I enjoy “pathologizing” posture. It gives me a sense of purpose.

Les Glennie, Registered Massage Therapist (yes, tongue-in-cheek)

What could possibly go wrong? What are the (physical) risks of poor posture? Part 1

Back pain is probably mostly not a risk of poor posture. And if not back pain, then probably not much else either.

This is the bottom line of a clear summary of good quality research by Peter O’Sullivan, Leon Straker, and Nic Saraceni (and expertise doesn’t get much more expert):38

“People adopt a range of different spine postures, and no single posture protects a person from back pain. People with both slumped and upright postures can experience back pain.”

And yet we do also have to make sense of experiences like this…

Weeks of back pain from slouching on a bar stool

I once sat at a bar with my wife and spent about twenty minutes leaning to my right while we ate and talked, an awkward position that got uncomfortable fast. I fidgeted for a few minutes before I realized what was going on, but it was too late: my low right back had already “cramped up.” It was painful for days, and then a slowly fading annoyance for weeks after that.

People with less vulnerability to body pain — especially younger people — do not relate well to that kind of story. They may be inclined to underestimate the severity of the pain, dismiss the timing as a coincidence, or to call it a problem with vulnerability rather than a postural problem. (And they may be right! More on this soon.) But it’s quite real for a great many people, especially older ones.

The existence of this kind of situation was shown in a large, interesting study of triggers for back pain — what were people doing when they were struck by an episode of acute back pain, basically.39 The results emphasized both that posture isn’t a major risk factor for back pain and that it isn’t nothing either. By far the two biggest risk factors both had something to do with temporary awkward postures:

- Being “distracted” was by far the biggest risk:

patients were twenty-five times more likely to be distracted “during an activity or task” right before an episode of back pain than at other times in the preceding couple days. Although the study didn’t specifically establish what is meant by “distraction,” I suspect those stories are much like the one I told above: the problem was not so much that I was in an awkward posture (which happens all the time), but that I was distracted and didn’t notice the awkwardness of my positioning until it was too late. - Although a distant second to distraction, “awkward posture” topped the list of more specific examples of “manual tasks” that were also risky, and it was notably a greater risk factor than heavy/awkward lifting (which in turn was actually one of the lowest risks, and got significantly lower with age — not what most people would predict).

Everyone will be happy to hear that sexual intercourse was not a common back pain trigger. Although I imagine it depends on how you do it.

So hopefully that makes it obvious that I’m not throwing the posture baby out with the bathwater. It’s clearly involved in body pain, even if it’s also clear that it’s not alone, and not dominant. I’ve seen countless cases where relatively obvious and avoidable postural and ergonomic stresses did seem to cause pain — and in many cases that pain was relieved easily enough just by avoiding an obviously poor posture.

On the other hand, most such cases actually involved only an imposed postural stress, as opposed to a lazy “poor posture.” This is a constant point of confusion and important to sort out. I think it’s the key to understanding why the “poor posture” should mostly be abandoned as a concept.

Postural stress versus poor posture

There is a big difference between “poor posture” and “postural stress,” but the distinction seems to be absent from most discussions of posture and ergonomics.

A postural stress is a challenge to your posture that is imposed on you, as opposed to something you’re doing to yourself out of laziness and moral turpitude. It’s situational, as opposed to being the result of a bad habit. Some examples of postural stresses:

- trying to sleep where it’s impossible to do so without putting your neck in an awkward position, like a plane or car seat

- a cashier whose till is positioned a little too far away, causing chronic reaching

- uncorrected vision problems, forcing routine squinting and awkward head repositioning

- a drywall installer who virtually lives in constant neck extension

- a nurse who must constantly stoop over patients, and perform extremely awkward patient lifts

- a writer who must type incessantly — not a bad habit, just something that some of us have to do!

But sometimes you are the source of postural stress. When the challenge is self-imposed by your own positioning and readily preventable, that is poor posture — it’s just relatively rare, something we mostly avoid doing to extremes.

There is overlap between poor posture and postural stress, of course. Carrying a heavy backpack slung over one shoulder is a good example: it’s technically a self-imposed inefficient use of the tool, not an inherent flaw in the tool, and yet it’s also often convenient and sometimes temporarily necessary.

Many postural stresses can be avoided if you recognize the problem, but

I recall a case of a man with truly awful chronic upper back pain and a nasty computer workstation. I remember my amazement as he described it to me. He was barely aware of it being a problem — I had to tease him about it, it was so absurd — but once the problem was pointed out, he made several easy improvements … and that was the end of his problem. I find it hard to think of that case as a “posture” case.

Another good example: the fiddle player who developed terrible pain in his shoulder. Incredibly, he did not tell me that he was a serious fiddle player, but just described himself as a shoulder pain patient and didn’t mention the fiddle at all. It was only after carefully quizzing him that I discovered he was practicing the fiddle for hours every day with his shoulder intensely hunched up, as fiddlers do. If he stopped playing, the pain would fade away over a few days. If he resumed, it would flare back up. He had been doing this for years, but didn’t think to mention any of that to me. And what a terrible dilemma: a clear postural stress required by a beloved activity! Maybe he didn’t mention the fiddle connection because he didn’t want that to be the problem. I’m sure he didn’t want quitting to be the solution. That guy loved playing the fiddle.

Ergonomics is the science of arranging or designing things for efficient use, specifically to avoid postural stress. Unfortunately, ergonomics is usually interpreted unimaginatively, with the result that most people think that ergonomics is just about choosing office chairs and changing the tilt on your keyboard. Lots of things can indeed be said about office chairs and the tilt of your keyboard — but it’s only the tip of the ergonomics iceberg.

What are the (physical) risks of poor posture? Part 2

We live in a gravity field that never quits: day in, day out, it pulls us unwaveringly towards the center of the earth. If we are chronically a little bit crooked, some muscle somewhere is going to have to work more than its fair share to keep us upright. Try this yourself: see how long you can stand leaning a few degrees to one side. Exaggerated imbalance gets uncomfortable fast. And subtle imbalance presumably gets uncomfortable slowly, for at least some people. And the discomfort often outlasts the stress. Why?

No one really knows, but here’s a theory:

Muscle functions painlessly and well under most conditions — it’s a high-performance tissue. It can get surprisingly sensitive, though, usually in fairly well-defined patches, which are popularly called muscle “knots” or trigger points. I have written a lot about this mysterious phenomenon (including my doubts that it’s even muscular40 — but at any rate it certainly is good at seeming muscular). It’s not clear exactly what biological conditions cause this sensitivity, and it’s notoriously unpredictable. But there is one good method of inducing trigger point pain: awkward postures.

Trigger points seem to be closely associated with a wide variety of other common pain problems. This surprisingly ordinary condition may even be the source many of the (non-arthritic) aches and pains suffered by the human race, especially low back pain.

If poor posture contributes to the formation of knots in tired muscles — which is far from proven, but it’s a reasonable hypothesis — then this might be the chief risk of poor posture, and it might be a good idea to try to improve it.

Several of the most important concepts in the article have already been covered above, and you can continue with more below, including a dozen sections of practical advice and tips — what matters most to the average reader.

But the next four sections are nerdier deep diving, about 1700 words worth — the size of a beefy blog post — and I’ve set them aside for the paying members of the Salamander Fan Club. There is good stuff in here:

- Vulnerability versus “the posture did it”

- What are the (physical) risks of poor posture? Part 3: Arthritis

- What are the non-physical risks of poor posture?

- Is the goal of good posture to “stand up straight”? To be “aligned”?

Most PainScience.com content is free and always will be.? Membership unlocks extra content like this for USD $5/month, and includes much more:

Almost everything on PainScience.com is free, including most blog posts, hundreds of articles, and large parts of articles that have member-areas. Member areas typically contain content that is interesting but less essential — dorky digressions, and extra detail that any keen reader would enjoy, but which the average visitor can take or leave.

PainScience.com is 100% reader-supported by memberships, book sales, and donations. That’s what keep the lights on and allow me to publish everything else (without ads).

- → access to many members-only sections of articles +

And more coming. This is a new program as of late 2021. I have created twelve large members-only areas so far — about 40,000 words, a small book’s worth. Articles with large chunks of exclusive content are:

- Does Epsom Salt Work?

- Quite a Stretch

- Heat for Pain and Rehab

- Your Back Is Not Out of Alignment

- Trigger Point Doubts

- Does Fascia Matter?

- Anxiety & Chronic Pain

- Does Massage Therapy Work?

- Does Posture Matter?

- A Deep Dive into Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness

- Does Ultrasound or Shockwave Therapy Work?

- A Painful Biological Glitch that Causes Pointless Inflammation

- Guide to Repetitive Strain Injuries

- Chronic, Subtle, Systemic Inflammation

- Vitamins, Minerals & Supplements for Pain & Healing

- Reviews of Pain Professions

- Articles with smaller members sections (more still being added):

- → audio versions of many articles +

There are audio versions of seven classic, big PainSci articles, which are available to both members and e-boxed set customers, or on request for visually impaired visitors, email me. See the Audio page. ❐

I also started recording audio versions of some blog posts for members in early 2022. These are shorter, and will soon greatly outnumber the audio versions of the featured articles.

- → premium subscription to the PainSci Updates newsletter +Sign-up to get the salamander in your inbox, 0–5 posts per week, mostly short, sometimes huge. You can sign-up for free and get most of them; members get more and their own RSS feed. The blog has existed for well over a decade now, and there are over a thousand posts in the library. ❐

Pause, cancel, or switch plans at any time. Payment data handled safely by Stripe.com. More about security & privacy. PainScience.com is a small publisher in Vancouver, Canada, since 2001. 🇨🇦

The salamander’s domain is for people who are serious about this subject matter. If you are serious — mostly professionals, of course, but many keen patients also sign-up — please support this kind of user-friendly, science-centric journalism. For more information, see the membership page. ❐

Vulnerability versus “the posture did it”

If it’s so easy to induce muscle sensitivity by fighting gravity and adopting awkward postures, why aren’t we all in agony all the time? Lots of people live in gravity! (Everyone but these lucky people.) And many people frequently have awkward postures, but never have pain problems.

So why me? Why so many others?

And is poor posture really the problem for me and so many others, or are some people just excessively vulnerable?

It’s probably both, but I’m skeptical about posture as the direct cause of anything. The range of asymmetry that people can tolerate is probably quite wide, highly variable, and generally narrower with age,41 but the average healthy person can probably easily tolerate “poor posture” with no problem. And if poor posture can’t really hurt a healthy person, it’s not much of a demon, is it?

On the other hand, more vulnerable people, people who get pain from trivial postural stress — people like me — do not have a posture problem so much as we have a pain problem. A vulnerability. The greater the vulnerability, the more it’s about the vulnerability and not the posture — awkward postures are just another thing that triggers pain (even if we are quite careful). It doesn’t really seem like posture is what needs troubleshooting there.

I’m a bit doubtful that anyone is wandering around in pain as they age because they were sloppy with their posture in the past. It’s possible, but I prefer this story: vulnerability increases with age, and we start to notice that postural challenges we once coped with easily are starting to get tricky. And almost everyone gets there eventually. The “worst” postures become problematic sooner, of course, but I doubt they are the cause — just the messenger, and the message is, “You don’t handle physical stresses like you used to.”

“Inflammaging” is the inexorable increase in systemic inflammation as we age, strongly associated with poor fitness, but there are probably many other causes as well. It is the most ubiquitous of many causes of vulnerability to chronic pain all of which seem more likely to cause trouble than posture.

What are the (physical) risks of poor posture? Part 3: Arthritis

All tissues wear out when the stress on them exceeds their capacity to heal and adapt. Degenerative arthritis is a universal human condition — everybody develops it eventually, to some degree. It seems like a super reasonable guess that tissues wear out unevenly when they are loaded unevenly — just like shoes wear out unevenly in proportion to how uneven your gait is.42 Some people develop arthritis much more quickly than others, and poor posture certainly is a likely suspect.

Plenty of research does confirm a logical connection between posture and arthritis. For instance, a 2012 study of knee arthritis — an ideal place to look43 — showed that people who already have arthritic knees are bigger leaners, and their gait is “consistently different” than people with healthy knees, and they probably weren’t walking differently because of pain. That is, the crookedness probably caused the arthritic pain, as opposed to arthritis just making them walk crookedly.44

On the other hand, we have all the evidence presented earlier — and much more — that janky biomechanics just generally don’t match up very well with chronic pain. Arthritis itself is often surprisingly painless. Again with the knee, one of the most popular theories in musculoskeletal medicine is that uneven control of the kneecap — due to abnormal anatomy and/or posture — will cause the cartilage on the underside of the kneecap to degenerate painfully, which in turn causes a common kind of knee pain, patellofemoral syndrome. And yet, in fact, degeneration of that patellar cartilage can be painless.45

I could go back and forth with the research all day, but the messiness of the evidence is the answer. Poor posture probably can hasten joint decay, but it’s definitely not a major factor.

What are the non-physical risks of poor posture?

Maybe poor posture can get us into an emotional rut. This is a more subtle postural problem: the “comfort zone” problem. (I promised not to spend too much time on this, but it does deserve a section.)

It’s relatively obvious that posture is shaped by mood and all kinds of other social and emotional factors. But this double-edged sword might cut the other way, too: posture may, to a modest extent, actually create and reinforce emotional states.

Yes, I am talking about “power posing” — a notoriously over-hyped idea.46 However, follow-up research has been solid enough that I feel comfortable concluding that a confident posture can influence our emotions at least a little.47 It may not be a huge effect, but it’s probably there.

If posture can influence emotions, then it’s no surprise that it could also change pain sensitivity, and there is some evidence of that too.48 So, here’s a free, easy pain relief tip at least partially based on some science: Stand tall! Assume a bold posture, a “power” posture. Or, as a mentor of mine liked to describe that posture: “Tits up!” It might actually reduce pain — a little. A temporary reduction in sensitivity is hardly a cure for chronic pain, if it works at all, but trying certainly isn’t going to do any harm.

Emotions, posture, and pain sensitivity probably do all influence each other to some degree. Most self-limiting behaviours have both postural effects and causes. The classic example is depression: a depressed person will adopt a distinctively depressed posture, which can be quite obvious to everyone around them.49 Less obviously, a depressed posture may also generate depression. Happy people who “try it on” will actually start to feel sad! And, conversely, sad people who adopt happy postures and expressions will feel a little better.

Cool, eh? Physicality and emotionality are probably not cleanly distinct! Imagine.

The blending with physicality is interesting, but the emotional dimensions of posture are interesting all by themselves. Above I defined a poor posture as an “unnecessary and problematic pattern.” That pattern may be emotionally problematic. It can both express emotional hangups and actually cause and reinforce them. Posture can be a self-limiting behaviour, something that actually keeps you in a poor state of mind.

We hold ourselves in a certain ways because they reflect our comfort with the positions — and our discomfort with other positions, such as “holding our head high.” Just as we eat comfort food to our detriment, we may also slouch comfortably to our detriment, constantly projecting to the world (and creating the reality) that we aren’t ready, or we’re depressed, or sullen, or bored with life, or whatever it may be. When we leave poor posture unchallenged, we also fail to leave our emotional comfort zone, which is generally necessary for personal growth. See Pain Relief from Personal Growth: Treating tough pain problems with the pursuit of emotional intelligence, life balance, and peacefulness.

Although it’s all a bit flaky and murky, I actually believe that posture’s relevance to emotional state and pain sensitivity may be the best reason to experiment with changing posture — which is more of a statement about how minor the physical risks.

To pretend to be calm is to be calm, in a way.

Gillian Flynn, Gone Girl

Is the goal of good posture to “stand up straight”? To be “aligned”?

Popular thinking about posture is dominated by the ideas of straightness and alignment. It’s quite simplistic, but it permeates even guru-level rhetoric about posture. (And just the fact that there are “posture gurus” is rather interesting, isn’t it? Why? They are gods of the gaps.50) Many posture gurus will talk about something like “an efficient response to gravity” with confidence, which is really just a fancy way of saying “straight and aligned.” I do not believe that anyone actually knows what an “efficient” posture is, and it is not necessarily defined only by straightness or precise verticality.

We are the only species on planet Earth that routinely stands upright, and there are many reasons to believe that our erectness is a biological compromise of questionable value and comfort. Scientists are not sure why we ever stood up in the first place, and there is no evidence today that standing up especially straight is necessarily the way to go … or has any survival benefit … or, if it does, that it will necessarily be comfortable …

Consider your spine. It is essentially the same spine owned by every mammal in the world. And nearly all of those mammals carry their spine horizontally. So where did we ever get the idea that we “should” stack our vertebrae one on top of the other as vertically as possible? There is clearly nothing about spines that requires idealized uprightness.

There is no obvious sign that our anatomy has significantly or effectively adapted to the upright position. For instance, the connective tissues of our abdomen are still similar to those of the quadrupeds: they are generally suited to holding our guts suspended below our horizontal lumbar spines… not for holding them like a sack tied to a vertical pole.

So I reject the “stand-up-straight” definition of good posture. Good posture is not necessarily about straightness! And yet it is essentially the only widely used definition, even by people with supposedly very sophisticated opinions about posture. You may think I’m blowing the guru-thing out of proportion, but it is literally true that there have been successful entrepreneurial empires based mainly on trademarking and selling the importance of straightness and a method of getting there and staying straight, and then there are probably ten times more successful businesses that may not be devoted to posture straightening in particular, but use it as one of their founding assumptions or marketing bullet points.

I am not saying we shouldn’t stand up fairly straight. I am just pointing out — yet again, in yet another way — the uncertainties associated with any idea about posture, even this most basic and universal one. There is good reason to doubt anyone who claims that good posture is a matter of being well-aligned.

↑ MEMBERS-ONLY AREA ↑

What is good posture?

A definition of good posture is necessarily much less precise than defining a poor posture, because it depends on what you want, and it’s essentially impossible to measure success. So here are a couple almost philosophical suggestions. I’ll let Morgan Freeman start it off …

Your best posture is your next posture.

Morgan Freeman

A good posture is probably “dynamic,” emphasizing change and movement. Keeping active, frequently changing our posture, and experimenting with new ways of moving through the world are probably good responses to the uncertainties of posture. It’s the same in spirit as the nutritional advice to eat a varied diet.51

Most people lead overly sedentary lives — 6–8 hours per day of inactivity, an hour more per day in 2018 than 200852 — and are also overly consistent in their limited physical activity; that is, even people active at work are often active in only one way, and they need variety in their movement. More movement — not any particular position, but more positions — is definitely a safe bet and a good start on a good posture.

A variety of postural behaviours will also help to strike a balance between the path of least resistance and obsessive and excessive effort, neither lazy nor overzealous. Do not stray too far from your comfort zone, but do not linger there either.

The odds are lousy that I actually said something attributed to me.

Morgan Freeman

Can you change posture?

Much of what we perceive as “poor posture” is the result of biological adaption over decades and is unlikely to change without a truly heroic effort — and perhaps not even then. In principle, humans can adapt to almost anything — in fact, it’s the law.53 However, the same principle dictates that change is slow and difficult.

Wear high heels for many years, and your calves will actually shorten,54 and it’s not clear how easily that can be undone. On the other hand, grow up climbing trees like the Twa people of Africa and you will earn amazingly limber calves that allow your ankles to bend halfway (45˚) to the shin55 — two to four times greater than the average urban person! (A good video of this flexibility has unfortunately disappeared from YouTube.)

“Squatting like a baby” is a faddish fitness goal — and hopelessly unrealistic for most people. But if you grow up squatting like the Hadza bushmen, it’s no problem!

As Todd Hargrove puts it, not only do these people squat like a baby, “they squat better than a baby.”

They maintained all the mobility they had as babies, but added strength, stability and skill. They never stretch, never do yoga or pilates, never engage in any corrective exercise, yet they all move effortlessly in and out of positions that most Westerners cannot even get into.

Which sounds great. But don’t think for a minute that the Twa and the Hadza don’t have their own costs and consequences for the stresses they’ve adapted so beautifully to. Everything in biology involves trade-offs.

Many adaptations are almost certainly irreversible—or so difficult that they might as well be. A child can adapt in ways that are possible only in the plasticity of a rapidly growing body, and for the adult to try to undo it is like trying to straighten wood that was once artfully bent with steam. Other changes may occur only over vast spans of time, or because of variables we have little or no control over. The result is that some adult “postures” are simply impossible to change — we really do get locked in.

And yet we can change. Stretch actually can increase flexibility, with a lot of work (more on this below), for whatever it is worth. For the office worker who feels locked into a typist’s hunch — I know I do, as I type this — isn’t it worth at least trying to break out? Is the near futility of it all the more reason to at least make the effort? Perhaps it is.

Should you try to change your posture?

There’s no basis for “shoulding” on anyone when it comes to posture. Even for people who have problems that might plausibly be attributable to poor posture or poor coping with postural stress, it’s a long shot. And if the only reason you want to change your posture is on principle? I really don’t recommend it — it’s just not worth the trouble. You are not a good candidate for this process. There are probably a hundred more useful things you could do with your time. Life is short!

But people really do that. I went through a whole phase in my twenties under the spell of a posture guru. I did all kinds of silly exercises to "optimize" my posture for months. I’m never getting that time back.

The cure can be worse than the disease. A genuinely strong postural habit is not unlike an addiction. Trying to live with better posture may cause more problems, or be more uncomfortable, than whatever it was that drove you to try to improve your posture in the first place. All to change something that probably isn’t much of a problem in the first place.

In a short article for The Guardian, Oliver Burkeman describes what it was like to switch to a special chair that “resembles a saddle, so instead of slouching, you perch. Or that’s the idea; in reality, it’s just rather uncomfortable. After 40 minutes, it’s extremely uncomfortable.”56 Change and challenge can be uncomfortable, and the payoff is uncertain. If Mr. Burkeman were to keep that up constantly for a decade, he might “toughen up” and be a better man for it, or he might find it a wearisome strain with no clear point! Hard to call.

However, if you are driven to the idea of postural transformation because of aches and pains, you may be quite motivated by the hope of a partial solution, and the side-effects of challenging new habits may be more worthwhile. You should probably try it, and keep it up for a while to give it an adequate chance, or even just for the sake of experiment.

Try to stay interested in the challenge for at least a month. Watch and wait patiently for new developments. It took me a good six months to learn how to stop sleeping face down … but now I can’t imagine going back. People who quit trying to change their posture after a week, or even after a month, have not learned much — except that they aren’t very good at it.

Be persistent and give it a fair chance. And then, if the first honest attempt doesn’t work? Give up.

What if you give postural change a fair chance, and there are no obvious benefits? What if you can’t really tell if you’ve achieved anything? What if you still seem to be crooked? Or what if you look straighter in the mirror, but it makes no difference to how you feel?

Definitely … give up.

I am all for trying anything once, and I think postural exercise is worth a shot if you think it might be connected to a pain problem. However, if a reasonable effort fails, I do not recommend a repeat performance. Once again, there are many better things you can do with your time — not just better things in general, but better things you can do to try to solve a pain problem.

There are simply too many problems, too many questions about posture’s relevance to pain. It’s worth trying to work with posture — but it’s not worth trying a lot.

Irregularity is to be expected in any biological form. Body parts are not interchangeable legos or Ikea furniture pieces made by factory molds. Wonkiness and asymmetry are part of the plan.

Playing With Movement, by Todd Hargrove, p. 169

Part 2

How do you improve posture?

I’ve spent the article so far mostly arguing that very few people need to try to change their postures, and probably no one needs to “worry” about it.

But a great many people will be convinced that they are the exception. At least 70% are wrong… but they are going to believe it anyway, and they are going to try to change their posture.

So let’s try to make that as effective as possible. Mostly by eliminating some common bad ideas.

For the rest of the article I will review some approaches to improving posture, mostly defined as “increasing postural fitness.” Whatever your approach, I recommend choosing clear, functional goals and/or solving specific problems. Rather than shooting for “good” posture, think mostly in terms of postural fitness and ask yourself: what do you want to be posturally fit for?

The example of “flexibility” is instructive: many people have a stretching habit with the specific goal of being more flexible, but they can’t explain why they need to be more flexible. Or, if they do, the need is trumped up, even ridiculous.57 Athletes especially tend to exaggerate their need for flexibility.58 Most people don’t need to be more than a tiny bit more flexible than they already are, if that.

Similarly, most people do not need to be posturally fit for activities that they will never actually do. It’s like buying an SUV for handling those rough roads you rarely even see. You don’t need to be able to balance on a tightrope unless you plan to work for a circus. Choose goals that make sense for you.

In general, goals for postural fitness are almost indistinguishable from general fitness. In other words, improved posture is something that emerges naturally out of being in good shape and pursuing functional goals.

The seemingly technical challenge of changing postural habits is nothing of the sort: it’s mostly in the realm of art and faith, not science and “hacks.” Measures of success are primarily subjective. I have witnessed and personally tried many tactics for changing postural habits. There are no rules, no system to which you should devote your life, no right way to do it.

But there are definitely wrong ways…

Improving posture by force of will

Trying to force yourself to earnestly sit or stand up straight is so ineffective and pointless that I wouldn’t even bring it up, except that … it’s actually the default approach. This is what most people do.

When people decide that they “really need to work on their posture,” they usually don’t have any clear idea what they intend to do. Most of the posture-worried go through episodes of trying this — usually in no particular way, just occasional spasms of effort until their discipline inevitably fades. It’s a more common impulse in the young, I think, because older people have generally long since lost faith that in the value of the exercise (even while the hope often persists).

Posture is the product of spinal reflexes and additional tweaking by your brain, all of which occurs — as it must — without the involvement of conscious attention. While you can always exert conscious control over your posture, you will always revert to the unconscious and reflex-controlled pattern the second your mind wanders. Consciousness is really just a thin scum on top of everything else the brain does.

If you are disciplined enough, perhaps you can sustain a posture long enough that the habitual, unconscious behaviour begins to change. But such discipline may have a price that not many people want to pay. To the extent that this ever succeeds, it tends to produce rigid and artificial postures — a caricature of posture, an imitation of good posture.59

Address major systemic barriers to success

Some problems will make it particularly difficult to improve your posture. It’s a good idea to try to solve them first … if you can. Obviously in many cases it won’t be easy, or even possible.

Most of these barriers to success with posture improvement are actually (much) more important for other reasons, so you really can’t lose. Any benefit they have for a posture improvement quest is just a little bit of gravy.

- Fatigue, especially from insomnia. A lot of insomnia is behavioural and treatable, even if it seems extremely severe and stubborn. Treating insomnia is the highest priority for this challenge, and almost any other health challenge.

- Pain, especially if it is actually caused by poor posture. A lot of unexplained and chronic body pain is untreatable. But some is. Common muscle pain is unpredictable, but often responsive to nearly any kind of fresh sensory input, like massage or stretching — so it’s certainly worth trying to address common aches and pains in this way before trying to improve posture.

- Mood disorders are a major barrier to postural change. I am not a mental health professional, and this is not the place to recommend any solutions for those problems. However, I have recovered (and stayed recovered) from severe depression — so I can at least say with confidence that it’s possible and relevant.

- A job with significant postural stress. By no means should everyone with a physically demanding job quit so that they can work on their posture. However, if you believe posture is an important issue for you and you have a job that makes it difficult, then you should certainly consider a change.

That's just a few examples of "lifestyle medicine." For several more, see: Vulnerability to Chronic Pain. But you get the idea: make working on posture easier. Imagine how hard it would be for someone with all of these problems: a tired, hurtin’, depressed person with a job leaning over a conveyor belt for several hours per day is probably going to have a really hard time changing postures.

Visualize, dramatize, and role-play

Rather than telling yourself to stand-up straighter, pretend to be someone who is better at it than you are, like a drill sergeant. “Fake it until you make it.”

This will sound pretty strange to a lot of people, you don’t have to be obvious about it. You’re not putting on a show, and no one has to know that you’re dramatizing anything. For instance, if you find it hard to lift your chest, lift your heart instead: walk down the street pretending to be three times more confident than you are (act “as if”) and watch what happens to your chest. If your back is uncomfortably curved (perhaps an seemingly excessive lordosis), then “walk like a dinosaur” — pretend you have an enormous, heavy, swaying tail as you walk.60 And so on.

Or "move happy moves" — move like a happy person would move, even if you don’t feel happy. Act happy! Todd Hargove of Better Movement:

It is usually quite obvious to people that changing their thoughts might be a good way to change their mood. For example, people might try to combat sadness or depression by “thinking happy thoughts.” Another possible approach would be to “move happy moves.”

Trigger self-awareness with reminders

Interrupt or remind yourself to pay attention to your posture goal using timers and buzzers … or whatever works. Maybe there's an app for that (guaranteed). Maybe it’s signs or oddly placed objects around your home or office.

For instance, if your specific postural goal is to break the habit of tucking your legs too tightly behind your chair legs (a common one), then it may be useful to frequently remind yourself about the problem, as opposed to trying to sustain discipline.

Practice makes perfect: spend deliberate time in different and novel postures

Some people will relate best to an exercise ritual — strive for your goal repeatedly or continuously until it gets easier. Repetition is required for most kinds of learning. If you want to carry your head further back, then go for a half-hour walk every day and practice keeping your head in the “right” place, or even further back than that. Don’t worry about practicing the rest of the time, any more than you would learn guitar by carrying it around with you at all times and strumming every time you can think of it. Just set up a conscious, well-defined practice time.

It may also be useful to make it more experimental and playful: rather that striving for an ideal, just explore different postures. Variety is the spice of life. Spending time in a posture that is unfamiliar to you may refine your sense of what is possible and desirable.

You could go another step and even experiment with seemingly bad postures: try them to see how they feel. This may highlight the difference from what you believe the be the ideal — or reveal that they aren’t as different as you thought.

Add some instability to your life! Improve posture with balance and coordination challenges

When submarine sailors are released from duty after a long time at sea, they are not allowed to drive for several days: their long-distance vision has atrophied, because they haven’t looked at anything further away than a few meters for weeks.

Similarly, after decades of living on flat and stable surfaces, most people probably do not have particularly good balance or robust postural strength. We are flatlanders. The reflexes that keep us upright can degenerate, and core strength declines. The consequences are probably subtle. For instance, our corroded reflexes might, over time, make workouts more difficult and unpleasant, chipping away at our enthusiasm. Although there’s no convincing evidence that this causes any kind of trouble — namely back pain — it might still be well worth doing in the name of general fitness and just in case it matters. We don’t have time to optimize our fitness in every possible way, but this way seems like a reasonable one, especially because it offers some general fitness value regardless of how important it is otherwise.

So, why not add some manageable postural challenges to your activities? Even otherwise sedentary activities! For instance, you can actually do this while you sit. There are lots of ways to give your postural reflexes and strength a little workout, but it’s particularly easy to just sit on an exercise ball or a wobble cushion instead of a chair while working at the computer.

Or get wobble board or balance board and stand on that … while you watch television.

If you’re lucky enough to live near a beach, walk on the sand. Sand walking and running are surprisingly difficult.

And so on. Many exercise activities are more obviously challenging to posture than others. Where else but in a yoga class are you going to be asked to stand on one leg? Pilates, taijiquan, dance, martial arts, even a general fitness class — all can specifically demand coordination and stability not ordinarily present in your life.

The perceived value of core strength has become big business. It has spawned new business and industries. CrossFit and Pilates and even yoga owe much of their popularity to the idea that we should exercise our core muscles more. A wobble cushion is no CrossFit class. But it is, in principle, a mild provocation therapy — a bit of a challenge, forcing us to adapt. It’s not a strong stimulus, but it’s not nothing, and it’s practically “free.” We can use them while we work in our chairs, without putting anything new on our schedule.

My personal Balance Fit™ by Sissell, perched on a stool I have had for decades now. Do I use my BF as often as I should? Of course not! Human nature being what it is. Do I still think I should use it? Sure — despite more than twenty years of skepticism about the clinical significance of posture, I still think this is a useful “exercise” tool.

More about stability cushions

A stability cushion is a sturdy air-filled rubber disc, about the size of a flattened beach ball, strong enough to sit or stand on. They are unstable, but they are called “stability” cushions because they are mostly intended to help you achieve stability, as in “core stability.” They challenge your stability … for whatever that is worth, but it’s probably worth something. These things are now a fixture in gyms, a basic functional training tool, like balance boards, but this article is focused on using them as an accessory for your office chair.

Some of the name brand stability cushions are Disc ‘O’ Sit, Sissel SitFit, Vive wobble cushion, and the STOTT Pilates stability cushion. There are plenty more generic or weakly branded ones as well.

Is a wobble cushion therapeutic?

I started prescribing stability cushions early in my career. I hoped to introduce some movement and stimulation into the stagnant postures of my many chair-bound clients. The idea was to keep their back muscles frisky and postural reflexes stimulated, and I hoped this would treat and prevent back pain. But my enthusiasm for wobble cushions has … wobbled. Sitting a lot is actually not a major risk factor for low back pain, as I eventually learned. And while a lack of exercise may be quite unhealthy in terms of general health, a wobble cushion is not going to put much of a dent in that problem. See The Trouble with Chairs for more information about the risks of sitting and sedentariness.

Using wobble cushions still makes sense to me, but only in a precautionary variety-is-the-spice-of-life way. They’re nice. It’s cheap and easy and a bit whimsical. So … why the heck not? I still think it’s a good idea, just not a terribly important one. It’s just a bit of light exercise.

Choosing to use a wobble cushion requires some commitment to the idea of exercising while you sit.

How to sit on a wobble cushion

Intermittently. Not constantly.

At first, most people want to sit on their new wobble cushion all day long, but the proper usage of this tool is intermittent: use it for about half an hour at a time, put it aside for a while, and then put it back on the chair. Take it on and off throughout the day.

Wobble cushions create variety in your sitting not only by providing an unstable surface to sit on, but by adding and removing them from your regular chair. It’s like having another chair! Or an additional feature on your skookum ergonomic chair.

It’s actually supposed to be uncomfortable, to a point. The purpose of the product is to make your sitting an active chore for your back muscles. A wobble cushion cannot compete with the comfort of slouching!

It is possible to slouch passively, even sitting on a wobble cushion. Bear in mind that you’re defeating the purpose if you allow yourself to simply fall off the back edge of your wobble cushion and rest on the back of your chair.

Concave or convex? Depends on how much instability you want. A convex wobble cushion is much more like sitting on a ball, which provides much more of the instability that is the point of the product. Others are concave, and therefore more stable … undermining the key feature of the product. On the other hand, you can probably sit for longer on a less wobbly wobble cushion. If you find a convex cushion too uncomfortable, a concave one might be an ideal compromise.

How to stand on a wobble cushion

Stand on it and see what happens! This is a good, simple test of balance. If you find it difficult to maintain your balance for more than 20 seconds, then just a little standing on a wobble cushion is a fine exercise for you.

If you need more of a challenge, stand on one foot. Wave your arms around.

There are many ways to use a wobble cushion as an exercise accessory. Imagine any exercise, and simply insert a wobble cushion under hands, feet, or bum: the unstable surface will make it more challenging, and recruit more musculature.

However, especially in a office context, I recommend just standing on it occasionally — a good thing to do with a 2-minute micro-break.

Improving your posture with medical tape or kinesiotape

Taping is a gentle way to force the issue — or not so gently, depending on how you do it. At its most extreme, a lot of medical tape with low elasticity can make it impossible to assume certain postures. For instance, to limit how far you can push your head forward, retract your head and (probably with help) apply a length of tape along your spine from your hairline to between your shoulder blades. The moment you try to move your head forward, you will get an unpleasant yank on your skin. No discipline required!

There are many modern “kinesio” tapes that are highly elastic and quite comfortable. These can be applied in the same way to make some postures harder and more obvious to you — increasing awareness — but not actually impossible or unpleasant.

Taping can replace a lot of discipline. For whatever it’s worth, it’s probably a fairly good way to experiment with trying to change your postural habits.

Other kinds of imposed limits and aversion therapyTaping is the most obvious example of making the “wrong” postures less possible or comfortable, but there are many other possibilities depending on your goals. The ultimate cliché of aversion therapy is electric shocks to discourage the wrong behaviour. I don’t recommended that, but there are all kinds of creative ways to correct yourself with less drama, to make the wrong posture uncomfortable enough to make them unappealing. If your chair is uncomfortable, for instance, you’re less likely to spend too much time in it!

The goal is to “adjust your defaults” (Kabat-Zinn’s phrase), to create a new normal. Earlier I mentioned Oliver Burkeman’s experiment with a chair he “perched” on and how it was “extremely uncomfortable,” but he then describes an interesting change:

Now I don’t sit for too long, because it’s simply no fun to do so. After a few weeks, I realised that something intriguing had happened: I’d switched my default state. Standing or strolling was now my automatic, baseline behaviour; sitting was something I actively “did”.

Is being forced to avoid an uncomfortable chair a victory? A lasting one? Or will Mr. Burkeman revert sooner or later to comfier furniture? My money is on reversion; I’m doubtful that his “defaults” had truly been “adjusted” — which is just another way of talking about breaking old habits and forming new ones, no more or less profound or reliable than resolutions made around January 1.

Nevertheless, it is an interesting way of trying to change your posture, or any bad habit, and probably as good as any other.

Stretching to improve posture

It’s a popular notion that poor posture is caused by “tight” muscles pulling on our skeletons unevenly, like pathological ship’s rigging. I recall an elaborate demonstration of this principle in massage therapy college. An instructor tied several strings to me to simulate muscles and pulled on them in various patterns to show how tightness could warp my posture. The demonstration wasn’t memorable for the reason he would have liked.61

Undoubtedly the best known specific form of this idea is that tight hamstrings cause bad posture, and therefore that stretching them will improve posture. This was specifically tested in a 2012 experiment.62 I’m afraid it didn’t work. Although hamstring extensibility was indeed improved by a fairly ordinary stretching program, it had no effect on posture. The results are probably all the more believable because I strongly suspect the researchers were hoping to prove that stretching hamstrings is good for posture, and researchers are remarkably good at finding what they hope to find. But it seems the data were just not there to exaggerate or distort.

If stretching hamstrings has no effect on posture, I doubt any other kind of stretching does either. So this is a dead end, and yet another of many examples of how stretching “works” only in the sense that it will make you a little more flexible, temporarily, but the value of that flexibility is dubious indeed. For many other examples, see Quite a Stretch.

Just move more: improve posture with general activity and movement snacks

If force of will is the worst way to improve posture, being generally physically active in a variety of ways may be the best: not only somewhat effective, but a good idea for many other reasons too, of course.

A sedentary lifestyle contributes significantly to the degeneration of postural reflexes. NASA discovered this while studying the physiological effects of inactivity. “Use it or lose it” is the unsurprising biological lesson here: organisms adapt quickly to stimuli and stresses, and atrophy quickly without them. Therefore, probably the simplest cure for eroded postural reflexes is to simply do more with your body — but nothing in particular.

While it might make sense to choose activities that are specifically challenging to your posture — and you can certainly do that if you choose (see the next section) — the spirit of this suggestion is that you can probably get decent bang for buck without focusing on posture-challenging activities. Just by doing anything you like: salsa dancing, swimming, golf, whatever. A physical challenge like paddling (dragon boating), for instance, forces you to learn how to use your upper body (very) differently. The risk is that you will simply take postural dysfunction into the new activity, but the great potential benefit is that the enthusiasm you feel for the new activity will magically inspire new habits. Many people have permanently broken old habits by taking up an exciting new activity that required being different to enjoy or succeed at.

Inspiration — not discipline!

But why not discipline too? Movement snacking

Microbreaking or is the strategy of taking small breaks from work and moving around to prevent the many deleterious effects of stillness. In particular, it’s an easy way to keep muscles from developing painful trigger points. It is a survival skill for every chair-bound office worker, student, computer user, or anyone at all whose work (or play) generally requires long hours of being sedentary. But here’s the nugget of the tip: just “taking a break” isn’t enough. Walking to the water cooler and back — while not a bad idea — does not constitute actual stimulation for back muscles that are screaming with stiffness. It is necessary to actually do something therapeutic with microbreaks, such as mobilizations, AKA joint mobility drills, or a bit of gratuitous stair-climbing.

For a brief overview of microbreaking alone, see Microbreaking. For a complete survival guide for sedentary work, see The Trouble with Chairs.

Ergonomics: the art of eliminating postural stresses

Posture is the elephant in the corner of the ergonomics room. The biggest misconception about ergonomics is that it’s about facilitating good posture. It’s much more about eliminating sources of postural stress — or it should be, anyway.

In practice, ergonomics seems to mostly be “commercialized posturology” these days — that is, it’s the product and marketing division of the “science” of posture. And it’s all the more potent because it contains the legit seed-of-truth at the centre of all debate about posture. It’s even a pretty good-sized seed, like an avocado pit. But with sooo much bollocks around it.

It’s amazing what quacks can sell without a seed of truth, just an emotionally appealing idea (“one weird trick”), or something that sounds plausible to the ignorant (“quantum”!), or a fascinating sensation (spinal popping). But when you add an actual nugget of legitimacy? A real baby in the bathwater? An industry is born! An industry powered by claims that reach far beyond that legitimate premise. Despite the seed of truth, the marketing of ergonomics products is mostly powered by a never-ending supply of hyperbolic hype about the clinical importance of posture.

Let’s consider ergonomics more idealistically. What should it be? What is it when you strip away the absurdly excessive pursuit of alignment?

Ergonomics is the not-quite-a-science of arranging or designing things for efficient use. Poor ergonomics not only creates direct postural stress challenges — such as reaching too high for a computer mouse — but may also force people to learn bad new habits in order to cope. Computers have made slouchers out of a lot of people.

Extremely poor ergonomic design is usually obvious, but there are many more subtle cases as well. Improving the ergonomic design of your office or home could be simple, but not every solution may be practical or affordable. For example, I frequently recommend investing in a headset for your phone so that you don’t cradle it with a tilted neck. Headset technology has become both effective and affordable, yet many people haven’t considered this solution. When you’re upgrading your ergonomics, try to think outside the box, and don’t just pick the low-hanging fruit: the best changes may require some hassle and/or expense.

I have often seen patients complain bitterly about their office chair. Being prone to aches and pains, I can’t imagine why anyone would put up with a really bad chair for more than about three days. Either the boss agrees to get you a new chair, or you go buy your own. But people balk at asking and balk at the expense. Talk about penny wise and pound stupid! It’s your back — if it’s being relentlessly irritated by a chair at work, change the chair, period, whatever it takes.