Complete Guide to Frozen Shoulder

An extremely detailed science-based guide to one of the strangest of all common musculoskeletal problems, for both patients and pros

Sometimes shoulders just seize up, painfully and mysteriously: frozen shoulder. It comes with other diseases, usually diabetes, or it follows traumas or periods of immobilisation — hold the shoulder in one position for long enough, and it actually may get stuck there. The shoulder is the only joint that often “freezes” like this.1 Frozen shoulder is a biological puzzle, and a common one. It’s hard to define precisely, diagnose accurately, or treat effectively. In fact, frozen shoulder treatment is one of the best examples of how musculoskeletal medicine is surprisingly primitive still.2

Sadly, the old idea that this is a self-limiting condition is flatly contradicted by modern evidence.3 There is hope — it can thaw spontaneously4— but many people will be frozen to some degree for a long time, measured in years.5

Adhesive capsulitis is the more formal term for frozen shoulder: it describes the characteristic stickyness that develops in the shoulder joint capsule. Sticky shoulder is probably a better name.

About two thirds of patients are women. No one knows why.

Frozen shoulder symptoms — the basics

Range of motion fails, slowly and painfully, usually just on one side.6 Most patients first notice that they are having trouble reaching bra clasps, hip pockets, and back itches. The painful early stage mostly involves aching or burning deep in the shoulder joint, sometimes extending into the upper arm, often worst at night. Sudden movements can cause surges of much sharper and more extreme pain. Many frozen shoulder patients consider it the worst pain they’ve ever endured. Much more detail about symptoms to come.

How common is frozen shoulder?

The classic number is 2% of the population, but that’s not based on much, and it was challenged by frozen shoulder expert Dr. Tim Bunker in 2010:

The condition is also less common than the usually quoted figure of 2% of the population. This figure was arrived at 40 years ago when shoulder disease was ill understood and frozen shoulder was used as a waste‐bin diagnosis for any stiff and painful shoulder.

Bunker argues that the upper limit is probably 0.75% of the population for cases involving clear contracture.7 But that is still almost one in a hundred people. It’s not common-cold common, but it’s not rare either. It’s red-hair common.

Frozen shoulder is also linked to some extremely common health problems, like diabetes at 10% of the population, and diabetes is much more common than it used to be, a proper epidemic.8 The rising tide of diabetes may be bringing frozen shoulder with it.

Nature of the beast: frozen shoulder is a biological glitch

Getting into more detail now, frozen shoulder involves fibrosis and/or contracture of the tendons, joint capsule, and other soft tissues surrounding the glenohumeral joint — the main ball joint of the shoulder — specifically the rotator cuff interval.9 In severe cases, the RC interval is “obliterated,” and the coracohumeral ligament is “transformed into a tough contracted band,”10 like arthritis of soft tissues.

This is all rather disease-like, much more so than most common musculoskeletal problems: clearly some kind of biological glitch, and not a “mechanical” breakdown. Most notably, it is not a repetitive strain injury. In fact, if anything, it’s the opposite of an overuse injury: when it appears to have a “cause,” it’s more like an under-use injury, often triggered by a period of shoulder immobilization, like being stuck in a sling after a fracture or stroke. But it may also occur after a trauma to the area, even when there is no pronounced immobilization.

It is probably related to broader health problems. It mostly hits people over the age of forty, much more so if you have diabetes and/or cardiovascular disease.11 Frozen shoulder is extremely common in diabetics: more than 12% of them will get frozen shoulder, and about 30% of people with a frozen shoulder also have diabetes.12

Those problems are commonly associated with obesity, and what they have in common is “metabolic syndrome” — trouble with managing fats and sugars in the blood, and chronic low-grade inflammation everywhere.

You can be inflamed systemically for many other reasons, too. Metabolic syndrome is just the most obvious and common culprit. Regardless of how you get inflamed, it’s linked to frozen shoulder.13

Chronic low grade inflammation is increasingly seen as a part of other orthopaedic conditions such as osteoarthritis — once considered a ‘cold’ wear and tear problem (as opposed to the far more overt and ‘hot’ inflammation of rheumatoid arthritis).

Summer is coming — Frozen Shoulder, Cocks (Noijam.com)

No one knows why the shoulder joint capsule in particular would be the tip of this dysfunctional iceberg. Why such a dramatic point of failure? Why that tissue in particular? No one knows. But the relationship between frozen shoulder and metabolic syndrome is clear, as well as other glitchy biology like hyperthyroidism.14 It is one of many conditions that fall short of frank, diagnosable autoimmune disease like rheumatoid arthritis or lupus, but is still obviously autoimmune in character and characterised by inflammatory over-reaction.

General biological vulnerability

Carpal tunnel syndrome, just like frozen shoulder, is a surprisingly weird condition that is definitely more complicated than just using your wrist too much. People with median nerve compression have a significantly increased risk of … wait for it… heart disease.15 Since carpal tunnel syndrome itself pretty clearly doesn’t cause heart disease, it’s more likely that there’s something about the biology of these patients that leads to both carpal tunnel syndrome and heart disease.

This kind of thing is true of all chronic pain problems to some degree: general biological vulnerability is often just as important as whatever is specifically wrong with the tissue. Things like smoking, sleep deprivation, and being out of shape are modifiable risk factors for any kind of chronic pain, but typically neglected. See Vulnerability to Chronic Pain.

So that may be true for all chronic pain, but it seems to be more true of frozen shoulder.

We know that smoking, for instance, is weirdly a major risk factor for shoulder problems,16 which likely includes frozen shoulder. Smoking contributes to the poor health that seems to make frozen shoulder more likely. Among its many notoriously harmful effects, smoking is also a factor in many kinds of chronic pain17 — but shoulders particularly tend to break down in smokers.

The good news is that general biological vulnerability is treatable. Most of the non-specific risk factors are modifiable (although it may be very tricky). I’ll return to the topic of general vulnerability when discussing treatment.

More specific genetic vulnerability

Dupuytren’s contracture is basically “frozen hand.”

There’s another weird link between frozen shoulder and another weird disease, both stronger and stranger than the diabetes link: roughly half of people with frozen shoulder also have a Dupuytren’s contracture — “frozen hand” — which is quite common and is probably caused by the same underlying problem with connective tissue seizing up.18 Although it causes such different symptoms that they seem more like pathological cousins than siblings, they are clearly related. Dr. Bunker: “This terrible triad of contracted shoulder, Dupuytren’s contracture and diabetes pervades this whole area of scientific enquiry.”19

Or it could be an infection? Surgery and vaccination as causes of shoulder joint infection

You can hardly crack a medical journal open these days without stumbling on another example of how wee beasties are guilty of causing unexpected trouble, a factor in yet another condition we didn’t realize was infectious. The canonical example is the role of H. pylori in stomach ulcers.20 There are many other fascinating examples.21

Including some cases of… frozen shoulder?

Propionibacterium acnes, a bacterium we want in our pores, but not in our shoulders.

Apparently sticking a probe into a shoulder, despite antiseptic precautions, sometimes results in an alien invasion of the joint. By pimple bugs! “P. acnes was the most prevalent organism,” researchers reported in 2017.22 Yes, that’s the acne bacteria, Propionibacterium acnes (which may be wrongly blamed for acne23).

P. acnes is a “powerful nonspecific immune stimulant” which probably does trigger some cases of frozen shoulder, failures of prostheses, some arthritis, and perhaps even sciatica.24 Its role in post-operative infection is probably simply because it’s an endemic skin critter, nearly impossible to completely eliminate from the site of any puncture. Push just a few of them deep into a joint, and they find a new home and cause new kinds of trouble.

Amazing.

Rather than an infection that is dangerous and acute, the kind of thing we already know is a risk after surgery, it’s almost polite at first: barely detectable, in fact, just a little inflammation. But then? The inflammation caused by fighting the infection blossoms into frozen shoulder, and then it starts to suck to be you.

This is probably more common than we want to know about. In a 2015 survey, about 29% of people with persistent symptoms after surgery had an infection, and most of those had P. Acnes specifically growing in their joints. Only 3% of control group patients had P. Acnes growth (which is a lot less, but still strikes me as surprisingly high).25

Only surgery? Probably not

This seems to only apply to people who’ve had surgery, based on the data we have so far. But I don’t think we can actually rule out the possibility of infection with other mechanisms. Like many conditions involving inexplicable inflammation of tissue, it’s possible that it only looks like the immune system is attacking our own tissues for no reason. How many “autoimmune” diseases are responses to infections we don’t understand yet? Pure speculation on my part — but plausible, I hope, and certainly intriguing.

If surgery can do it, then there’s probably another way for P. acnes to catch a ride into the joint capsule…

Shoulder injury related to injections

The number one candidate for a non-surgical mechanism of infection is injection. While injections cause a lot fewer complications than surgery, anything that breaks the skin is still “invasive” and involves some infection risk. The most common injections are vaccinations, which is why this phenomenon is often referred to as “shoulder injury related to vaccine administration” (SIRVA) — a terrible term that seems to go out of its way to emphasize the wrong thing.26

Most injections are in the shoulder, because most injections are intramuscular, and the shoulder is a convenient spot with a bunch of muscle. But

During physical examination and on ultrasound scan, SIRVA will not appear to be any different from routine shoulder injuries. The only difference is that the shoulder symptoms will have started within days of a vaccination.

But is that the “only difference”? It’s not really normal for a minor physical trauma to drag on for weeks and months. It seems like something more might be going on here.

Unfortunately, it’s plausible that injections can trigger genuine adhesive capsulitis by the mechanism described above: the needle drags P. acnes into the joint capsule, just like surgery can, and then excessive and prolonged inflammation ensues, more than minor physical trauma would ever cause, creating a genuine case of frozen shoulder.

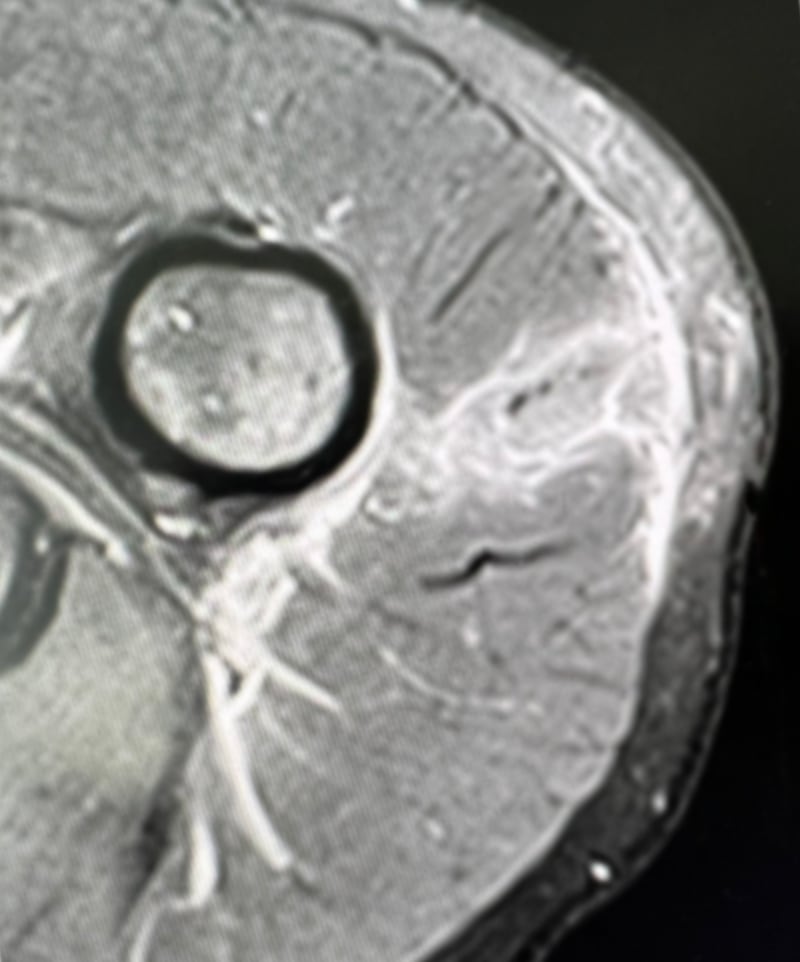

An MRI of injection trauma, known as a “vaccine” injury even though it can be caused by any injection. This image shows the injected contents, highlighted by inflammation, spreading from the skin all the way into the joint capsule. Used with permission.

Citation needed, but where there’s smoke…

Injection injuries are certainly a real thing, and frozen shoulder is a real thing, but do they overlap? Is there any evidence that injection injury specifically can cause frozen shoulder, via the mechanism of P. acnes infection? Not direct evidence, no. This is the closest we’ve got: a 2015 paper reported three cases of injection injury followed by a confirmed diagnosis of frozen shoulder:29

But this is also about as where-there’s-smoke-there’s-fire as you can get. Infection as a complication of both surgery and injection are plausible, and there’s good evidence of the first. And it’s also plausible that such infection could lead to frozen shoulder, and there’s also both direct and indirect evidence for that (discussed above). From these premises, it’s just a short, reasonable hop to the hypothesis that injection injuries can cause frozen shoulder: far from proven, definitely possible.

Injection safety

The next time I get an injection — probably a vaccination, which I obviously will do, because the benefits dramatically outweigh the risks — I’m going to drown my shoulder in rubbing alcohol immediately beforehand. I want exactly zero surviving P. Acnes on my skin when that needle goes in!

“I say we take off & nuke the entire site from orbit. It’s the only way to be sure.”

Or just don’t get shots in the shoulder? Surgeon Dr. Michael Skyhar: “This is all avoidable by simply asking that the vaccine be placed in a different location, such as the upper/outer buttocks.” Unfortunately, that may not be an upgrade! Gluteal injections risk an even worse injury to the sciatic nerve, “a persistent and global problem.”30 If done correctly, the risk can be reduced to almost zero… but that can be said of deltoid injections too. Is it worth avoiding the risk of frozen shoulder by pivoting to a similar or even worse risk of doing serious damage to a hip?️

Systemic infection

There’s no direct evidence that frozen shoulder is triggered by systemic infections — illnesses like the flu, or COVID-19! — but it is quite plausible. A 2021 paper reported on twelve cases closely following COVID infections.31 Anything that provokes widespread inflammation might push a vulnerable shoulder over the edge. And a phenomenon like this could easily get missed by the literature. If you think your frozen shoulder started with a systemic infection, please tell me your story.

Shoulder neglect? An evolutionary perspective on frozen shoulder

An interesting theory is that frozen shoulder occurs because “the human shoulder evolved for high speed projectile throwing,”32 and it suffers from neglect in modern living. Sedentary tissues can cause trouble, and be more vulnerable to biological failure. In particular, Pietrzak suggests, injury near the shoulder might trigger an inflammatory reaction that’s just waiting to happen.

I think it’s unlikely that the shoulder actually “evolved” for that purpose in the first place,33 and, even if it did, why would the shoulder be the only anatomy in the body with this problem?

But there’s some strong support for Pietrzak’s idea. In 2013, Littlewood et al. made a detailed argument that the symptoms of rotator cuff tendinopathy — and the shoulder joint capsule is essentially just a bunch of rotator cuff tendons — can occur without any actual or impending tissue damage.34 First they make the case that explanations for pain based on “peripherally driven nociceptive mechanisms secondary to structural abnormality, or failed healing, appear inadequate” — at least in the context of rotator cuff tendinopathy (and probably much else). They’re on firm ground with that premise. So what is the problem? They propose that the brain may react to relative overuse of de-conditioned tendon — tendon that’s just been lazing around too much — with fearful avoidance of movement, a vicious cycle of painful inhibition of function. This is completely consistent with Pietrzak’s idea. And “functional freezing” is the next major topic …

This video shows “fake” shoulder range of motion: lifting the entire shoulder, rather than actually using the ball-and-socket joint. Good scapulothoracic motion with no glenohumeral action at all. More about this below when we talk about diagnosis.

Stiff but not “frozen”: the case for functional freezing

“Adhesive” capsulitis refers to a literal stuckness, and there’s no question that many frozen shoulders are literally stuck in a limited range. But could some frozen shoulders be less literally stuck? Could that stuckness sometimes be more of a functional limitation than a physical one? Is it even possible that many cases are at least partially like this? What if, say, 60% of cases were 30% explained not by sticky joint capsule, but by an extreme reluctance to move — by neurological inhibition?

In a minor way, everyone’s joints “freeze” like this eventually. Joint stiffness, especially after being still for a while, is probably a non-specific reaction to practically anything that can go wrong with a joint. For many people, their first experience with this is after joint injuries in their youth — but it’s so obviously related to and in sync with recovery from the injury that it’s unremarkable. And then, years later, it’s usually the first symptom of arthritis. This stiffness is almost certainly protective and not a physical limitation, but neurological inhibition.35 Its purpose is to limit risk exposure for a joint the nervous system is “worried” about. In other words, it’s how the body says, “Careful now… no sudden moves…”

Any normal process in the body is usually represented by more extreme examples in some people, or in particular anatomy, and there are definitely some more dramatic examples of joint inhibition: some people’s quadriceps muscles shut down after knee trauma, a well-described phenomenon known as arthrogenic muscle inhibition.36 The muscle just stops doing its job so completely that it starts to atrophy: “My quad is deflating daily, like a slow tire leak.”37

If it can happen to the knees, maybe it can happen to other joints — it’s not clear why it would be so well-known about knees and not at all about shoulders, but it could still be true.38

Not all frozen shoulders are contractured

When you open frozen shoulders up, not all of them have clear visible signs of disease. Dr. Tim Bunker believes that only about 50% of patients diagnosed with the condition actually have obvious signs of pathology in the shoulder.39

That suggests that quite a few cases are functionally frozen.

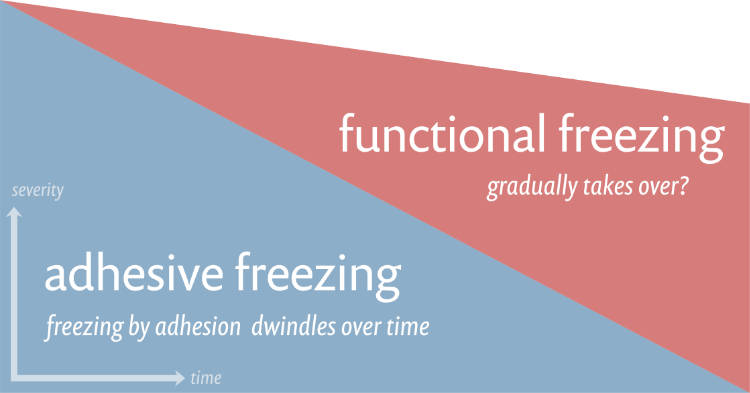

And could functional limitation be more prevalant in cases that are dragging on and on? Do some people slowly climb out of the frying pan of a sticky joint capsule and into the fire of a shoulder that’s just too uncomfortable to move? What if the door of shoulder movement stealthily transitioned from welded shut to just being rusted shut?

There’s hope in them thar hills, because a functional stiffness might be easier to loosen up (with massage, say, or carefully planned exercise). And yet the opportunity might be tragically missed! How would a patient even know that the situation had changed? There’s no easy way to tell that something badly stuck is less badly stuck than it used to be.

I’ve used a lot of questions to introduce this topic because — surprise surprise — no one actually knows. It’s a popular idea.40 There’s an accumulation of clues that the usual suspects aren’t cutting it, evidence that we’re missing something (which is what Littlewood et al. is all about). And we have clinical stories that seem to suggest it.41 And some recent evidence.

Well that’s interesting: “stuck” shoulders not so stuck when unconscious

In 2015, someone finally did a nice science experiment on this, simple and directly relevant.42 Five capsular release surgery patients were checked before and after being put under general anaesthesia. All five of them had “significantly more passive shoulder abduction” when they were knocked out … which would be impossible if their capsules were actually contractured or adhered or full of cement or any physical limitation. The improvement in ROM ranged from a minimum of 44˚ all the way up to a 110˚ boost (all the way back to normal). The researchers reasonably concluded:

Passive range of motion loss in frozen shoulder is not fully explained by a true capsular contracture alone. Passive shoulder abduction ROM assessed in awake patients with frozen shoulder does not accurately reflect the true available ROM of the affected shoulder. It appears that active stiffness or muscle guarding is a major contributing factor to reduced ROM in patients with frozen shoulder.

If I was the surgeon, I might have found it ethically hard to justify operating on these shoulders after seeing that.

Case closed? No, not yet. It’s really a shame it was such a small study. We really need someone to do the same thing with five times as many patients. But it is quite suggestive. One of those things that make you go, “Hmmmm!”

The worst cases probably really are dominated by adhesion. Worrying about a functional limitation, especially in the earlier stages of freezing, may be like trying to sweep up the ashes while the fire is still raging. But the possibility really shouldn’t be ignored, especially later on. It just might be the most important thing anyone can learn about this bizarre condition, mainly because it suggests several treatment options that are much more useful if there’s functional freezing, like strengthening, massage, or even Tiger Balm.

Over time, it’s possible that a functional limitation gradually becomes responsible for a larger share of the immobility and pain of the condition. It probably wouldn’t sustain the full ferocity of the condition, so I’ve depicted a slope downwards representing a general decline in severity — but of course the mixture over time could vary a lot from patient to patient.

How does “functional freezing” cause frozen shoulder?

There are three main ways that a functional limitation of shoulder ROM would probably work, and we shouldn’t underestimate their potential power:

- The brain can “shut down” a joint with neurological inhibition.

- The brain might do that to the joint because it has become sensitized.

- The muscles may have gotten rotten with “knots” (trigger points)

The brain is the boss of all function, and when it decides that a joint shouldn’t move, then it’s not going to move — and because your conscious mind isn’t included in the decision, the limitation can feel externally imposed. Your shoulder might as well be in a vice. Inhibition doesn’t feel “functional”: it just feels like you can’t move. Will power doesn’t come into this. Your brain is protecting you from yourself (or so it hopes). This is standard neurological procedure with any significant trauma.

How the brain handles a shoulder fracture

In the spring of 2020, my mother-in-law fell while she was on a walk in Palm Springs and fractured her arm: two deep cracks in the neck of the humerus, right up at the joint, and another crack in the rim of the socket (glenoid fossa). Her shoulder instantly shut down — normal range of motion one minute, 100% loss of ROM the next.

That was a neurological lockdown.

When the lockdown ended, her range of motion was almost fully restored in just a few days, which is typical. When the limitation was neurologically imposed, it can also easily be lifted. Once the brain decided it was safe, there was nothing to stop movement. In the case of frozen shoulder, there might well be some physical limitation in addition to the neurological one, but that wouldn’t happen in the case of a simple fracture.

And then she had a setback! At the six-week mark, she woke up in pain… and the movement ban had slammed down again, her brain being extra cautious. Again. X-rays confirmed she had not re-broken her arm (phew!) but there was significant swelling. Most likely she simply irritated the fracture site. The important point is that the effect on movement was disproportionate, extreme, and completely under the control of the nervous system.

If it can happen so clearly in that relatively simple case, you can bet your boots it can happen to varying degrees in messier clinical situations.

Why would a brain lock a joint that isn’t obviously injured?

It might do it if the pain has become like an oversensitive alarm that’s always going off when there’s nothing really all that wrong. “Sensitization” is well-described, and it’s what puts the “chronic” in chronic pain (there’s a chapter on this below). It is the main mechanism by which pain gets stubborn and unrealistic, a neurological over-reaction. Pain is all about detecting threats and changing behaviour to avoid them. If your brain is convinced that your shoulder is in more danger than it really is, it will both hurt more and get shut down.

Trigger points are a tough topic, because no one really knows exactly what they are, but there’s no question that people often develop sensitive spots in soft tissue, and there’s usually more of them in troubled areas. Although their nature is unexplained and controversial,43 the usual way of explaining them seems like a great fit for frozen shoulder: “tiny cramps” in the muscle would make it uncomfortable, weak, and less stretchy, like a knotted bungie cord. If the rotator cuff and other shoulder muscles were full of trigger points, perhaps the net effect would feel an awful lot like literal “freezing.”

I’ll discuss dis-inhibition and de-sensitization strategies below, as well as the (hopelessly imperfect) options for trying to treat trigger points.

Muscle guarding may freeze shoulders. If so, we aren’t sure why the muscles do it. Is it a psychological thing?

Shrunk, not stuck: a 150-year history of misleading names for frozen shoulder

The earliest medical description of frozen shoulder dates to 1872, when Simon-Emmanuel Duplay called it periarthritis of the shoulder,44 and for a while various shoulder problems were (incorrectly) attributed to the idea of “periarthritis,” and for a while Duplays Disease was used to describe several shoulder problems.

The term “frozen shoulder” was coined by a Boston surgeon, Ernest Amory Codman, in 1934, in his book about the shoulder.45 Codman was the first to more thoroughly and precisely describe the condition, and he coined its popular name which is still in wide use today — although perhaps it shouldn’t be, as we’ll see. (Codman was also the first American doctor to systematically track patients through recovery, which is pretty cool: he was ahead of his time.)

The term “adhesive capsulitis” arrived in 1945 when Dr. Julius Neviaser described the texture of the joint capsule as “adhesive,” comparing it to a sticking plaster — an archaic term for a small medical dressing, AKA a bandage.46

These days, adhesive capsulitis is usually seen as the most modern and precise descriptive jargon for the condition, but perhaps it’s no better than “periarthritis.”

“Adhesive” is probably the wrong word: shrunk, not stuck

There is no detail of this condition that isn’t controversial and mysterious, and what shows it better than a challenge to its very name? Nagy et al. (among others) argue that “adhesive” is inaccurate:47 it’s not an adhered joint capsule, but rather a contractured one.

Contracture is the shortening or hardening of tissue. In more familiar words, they’re saying the joint has been “shrink wrapped” by a joint capsule that has tightened, rather than surrounded by loose layers of joint capsule that have gotten stuck together.

To drive home the idea of contraction, there is literally less room in a frozen shoulder: the joint capsule, normally quite loose and roomy and filled with 15–25 ml of joint sauce (“synovial fluid”), can shrink so much that there’s almost no lube left, just 5 ml!4849 Definitely a “fun fact” about frozen shoulder. As reckoned by joint fluid, that’s a loss of roughly 75% of the space in the capsule.

So what’s in a name? Maybe a lot in this case: this difference could be extremely important to treatment. Sticky layers can be pulled apart; contracture is an issue that’s probably a lot harder to force…

END OF FREE INTRODUCTION

Purchase full access to this tutorial for USD$1995. Continue reading this page immediately after purchase. See a complete table of contents below. Most content on PainScience.com is free.?

Almost everything on this website is free: about 80% of the site by wordcount, or 95% of the bigger pages. This page is only one of a few big ones that have a price tag. There are also hundreds of free articles. Book sales — over 74,500 since 2007?This is a tough number for anyone to audit, because my customer database is completely private and highly secure. But if a regulatory agency ever said “show us your math,” I certainly could! This count is automatically updated once every day or two, and rounded down to the nearest 100. Due to some oddities in technology over the years, it’s probably a bit of an underestimate. — keep the lights on and allow me to publish everything else (without ads).

Q. Ack, what’s with that surprise price tag?!

A. I know it can make a poor impression, but I have to make a living and this is the best way I’ve found to keep the lights on here.

Paying in your own (non-USD) currency is always cheaper! My prices are set slightly lower than current exchange rates, but most cards charge extra for conversion.

Example: as a Canadian, if I pay $19.95 USD, my credit card converts it at a high rate and charges me $26.58 CAD. But if I select Canadian dollars here, I pay only $24.95 CAD.

Why so different? If you pay in United States dollars (USD), your credit card will convert the USD price to your card’s native currency, but the card companies often charge too much for conversion — it’s a way for them to make a little extra money, of course. So I offer my customers prices converted at slightly better than the current rate.

refund at any time, in a week or a year

call 778-968-0930 for purchase help

| company | PainScience.com |

|---|---|

| owner | Paul Ingraham |

| contact | 778-968-0930 |

| refunds | 100%, no time limit +Customers are welcome to ask for a refund months after purchase — I understand that it can take time to decide if information like this was worth the price for you. |

| more info | policies page ❐ |

| payments |

- What do you get, exactly? An online tutorial, book-length (52 chapters). Free updates forever, read on any device, and lend it out. E-book only! MORE

- Secure payment takes about 2 minutes. No password or login: when payment is confirmed, you are instantly granted full, permanent access to this page.MORE

- Collect them all. Get an “e-boxed” set of all 10 PainScience.com tutorials, ideal for pros … or patients with a lot of problems.MORE

Q. What am I buying? Is there an actual paper book?

A. Payment unlocks access to 44 more chapters of what is basically a huge webpage. There is no paper book — I only sell book-length online tutorials. This format is great for instant delivery, and many other benefits “traditional” e-books can’t offer, especially hassle-free lending and updates. You get free lifetime access to the always-current “live” web version (and offline reading is easy too).

Read on any device. Lend it out. New editions free forever.

Q. I just don’t like reading on the computer! Is there any way around that?

A. The design and technology of the book is ideal for reading on tablets and smart phones. You can also print the book on a home printer.

Q. Can I lend the tutorial out?

A. Yes! Feel free to lend your tutorial: I do not impose silly lending limits like with most other ebooks. No complicated policies or rules, just the honour system! You buy it, you can share it. You can also give it as a gift.

Q. Is it safe to use my credit card on your website?

A. Literally safer than a bank machine. Payments are powered by Stripe, which has an A+ Better Business Bureau rating. Card info never touches my servers. It’s easy to verify my identity and the legitimacy of my business: just Google me [new tab/window].

Q. I can really get a refund at any time?

A. Yes. All PainScience.com ebooks have a lifetime money-back guarantee.

Q. Why do you ask for contact information?

A. To prevent fraud and help with order lookups. You aren’t “subscribing” to anything: I never send email to customers except to confirm purchases.

Q. Can I buy this anywhere else? Amazon?

A. Not yet. Maybe someday.

See the “fine print page” for more about security, privacy, and refunds. No legalese, just plain English.

Save a bundle on a bundle

The e-boxed set is a bundle of all 10 book-length tutorials for sale on PainScience.com: 10 books about 10 different common injuries and pain problems. All ten topics are (all links open free intros in a new tab/window): muscle strain, muscle pain, back and neck pain, two kinds of runner’s knee (IT band syndrome and patellofemoral pain), shin splints, plantar fasciitis, and frozen shoulder. (Headache coming soon, fall of 2019.)

Most patients only need one book, because most patients have only one problem. But the set is ideal for professionals, and some keen patients do want all of them, for the education, and for lending to friends and family. And, of course, you do get a substantial discount for the bulk purchase. But no rush—complete the set later, minus the price of any books already bought. More information and purchase options.

You can also keep reading more without buying. Here are some other free samples from the book:

- “Windows of Opportunity” in Rehab — The importance of WOO in recovery from injury and chronic pain (using frozen shoulder as an major example)

- Vibration Therapies, from Massage Guns to Jacuzzis — What are the medical benefits of vibrating massage and other kinds of tissue jiggling?

- The Role of “Spasm” in Frozen Shoulder — How to identify cases of functional frozen shoulder, dominated by muscular inhibition

And several other related free articles on PainScience.com:

- Guide to Repetitive Strain Injuries — Frozen shoulder is not a repetitive strain injury, but a lot of people suspect that it is.

- Vulnerability to Chronic Pain — The stubborness of many problems is due to preexisting biology vulnerabilities, and frozen shoulder more than most.

- Dupuytren’s Contracture — A biological cousin to frozen shoulder.

- Does Fascia Matter? — Frozen shoulder is one of the few obvious examples of a clinically relevant problem with “fascia” (sort of).

- PF-ROM Exercises — Gentle dynamic joint mobility drills are the single most important component of treating frozen shoulder.

- Progressive Training — The principle of progressive rehab is vital for frozen shoulder patients.

- Muscle Pain as an Injury Complication — Many frozen shoulder patients probably suffer from significant long-term complications of this type.

- Three especially good muscles to massage that might help some cases of frozen shoulder: • pectoralis major • infraspinatus, teres minor • scalenes (anterior, middle, posterior).

The trouble with Dr. Google and why this book matters

In the many years since I’ve been writing about painful problems like frozen shoulder, there has been an explosion of shabby information about every condition. Shockingly, this has not resulted in patients or health care professionals being better informed. Most of the information that you can find out there repeats the same oversimplified conventional wisdom … much of which is just wrong. A particularly good example is the way “adhesive” capsulitis is probably the wrong name for the condition, a mistake based on early, incorrect assumptions about the pathophysiology that almost no one seems to know about yet.

Scientists have actually proven that “Dr. Google” is incompetent — just in case you needed any convincing.+

In 2012, the The Journal of Foot & Ankle Surgery ranked 136 websites about common foot and ankle diagnoses. Expert reviewers gave each a quality score on a scale of 100. The average score? Just below fifty. Fifty! See Smith et al.

Or see Starman et al. for a review of other kinds of health care information (with nearly identical grades).

P.S. These references are aging now… but nothing’s really changed!

I’ve been obsessively updating this tutorial for about 9 years now. By 2018, it was the largest and best of its kind as far as I could tell. I had already mined the best ideas I could find from the most detailed sources, and surpassed them — more information, more fun, and more rigorous. And then I kept going, while everything else seems to have stood still. Blog posts that haven’t been updated. Myths repeated ad nauseam for decades now. Big medical publishers that haven’t added anything to their shallow frozen shoulder summaries in years, and you wouldn’t enjoy reading it if they did.

So what can I do for you?

There is no cure for frozen shoulder syndrome. Of course not! Wouldn’t it be great if there were a proven treatment with minimal cost, inconvenience, or side effects? But we’re nowhere close to this for frozen shoulder. This book wouldn’t need to exist if there were.

What I can do is explain and review all the imperfect options so that you can prioritize them. I can help you confirm your diagnosis and debunk bad ideas. Some people will finally enjoy a breakthrough after reading this tutorial, and get partial or complete relief of their symptoms, sometimes temporary, sometimes lasting. And maybe that is kind of miraculous!

Just reading it might help. Online tutorials like this one might actually be able to directly help people with chronic pain — the evidence supports that, at least a little+Dear BF, Gandy M, Karin E, et al. The Pain Course: A Randomised Controlled Trial Examining an Internet-Delivered Pain Management Program when Provided with Different Levels of Clinician Support. Pain. 2015 May. PubMed 26039902 ❐

Researchers tested a series of web-based pain management tutorials on people who had been suffering for more than six months. No matter how much (or little) help they had from doctors and therapists, they all experienced significant reductions in disability, anxiety, and average pain levels, for at least three months. Basic knowledge is fine for basic cases, but more and better information is important for the tough ones. And even if you only recently developed frozen shoulder for the first time, how long do you want to spend following poor quality advice or muddling about with partial understanding? Get started on the right foot.

All of that is hopefully worth more than several sessions of physical therapy, at a fraction of the cost.

Paying in your own (non-USD) currency is always cheaper! My prices are set slightly lower than current exchange rates, but most cards charge extra for conversion.

Example: as a Canadian, if I pay $19.95 USD, my credit card converts it at a high rate and charges me $26.58 CAD. But if I select Canadian dollars here, I pay only $24.95 CAD.

Why so different? If you pay in United States dollars (USD), your credit card will convert the USD price to your card’s native currency, but the card companies often charge too much for conversion — it’s a way for them to make a little extra money, of course. So I offer my customers prices converted at slightly better than the current rate.

refund at any time, in a week or a year

call 778-968-0930 for purchase help

Part 1.8

Appendices

Related Reading

A Painful Biological Glitch that Causes Pointless Inflammation — The inflammation of frozen shoulder is exasperatingly mysterious. This article explains how inflammation can be “glitchy” — an interesting perspective that might help make sense of frozen shoulder.

Muscle Pain as an Injury Complication — The story of a difficult shoulder rehab. Although not a case of adhesive capsulitis, there’s lots of relevant detail about how any shoulder pain can get stubborn.

Guide to Repetitive Strain Injuries — Frozen shoulder isn’t an overuse injury, but it is often mistaken for one, and most of the RSIs are just as odd and surprising as frozen shoulder is, in their own ways. This article explores five surprising and important facts about conditions like carpal tunnel syndrome, tendinitis, or iliotibial band.

Dupuytren’s Contracture — Frozen shoulder is probably in the same pathological family as this common hand condition that slowly causes the hand to flex into a claw. The palm “shrinks” much like the shoulder joint capsule.

What’s new in the frozen shoulder book?

Regular updates are a key feature of PainScience.com tutorials. As new science and information becomes available, I upgrade them, and the most recent version is always automatically available to customers. Unlike regular books, and even e-books (which can be obsolete by the time they are published, and can go years between editions) this document is updated at least once every three months and often much more. I also log updates, making it easy for readers to see what’s changed. This tutorial has gotten 102 major and minor updates since I started logging carefully in late 2009 (plus countless minor tweaks and touch-ups).

Nov 11, 2024 — Science updated: Added an encouraging anecdote about steroids working really well for frozen shoulder, and a section about the huge GRASP trial of steroids vs. exercise (not for frozen shoulder, but still relevant). [Updated section: Steroids, injected and swallowed.]

2024 — Added: A new entry for the hall of treatment shame: “Tok sen massage (hammer-and-wedge, from an extremely popular Internet video).” [Updated section: Hall of treatment shame: the most bogus frozen shoulder treatments.]

2022 — Minor addition: Added a small sub-section to recommend the “pendulum” exercise. Simple but nice. [Updated section: Use it or lose it: movement therapy.]

2022 — Science update: Added a minor but neat point about how much joint fluid volume is lost in frozen shoulder. [Updated section: Shrunk, not stuck: a 150-year history of misleading names for frozen shoulder.]

2021 — New chapter: A substantive new chapter about the possible role of the mind and muscle guarding in frozen shoulder. [Updated section: Can the mind freeze shoulders? Or unfreeze them?]

2021 — Proofreading: It was time for an annual book tune-up: a few dozen minor errors have been corrected.

2021 — Science update: Small but fascinating science update about Ascani et al., exploring a possible link between frozen shoulder and COVID. [Updated section: Or it could be an infection? Surgery and vaccination as causes of shoulder joint infection.]

2021 — Minor polishing: A little editorial polish, and a bit of elaboration about the role of psychotropic effects. [Updated section: The cannabinoids: marijuana and hemp, THC and CBD — “it’s complicated!”.]

2020 — Science update: Minor citation to Ainsworth on ultrasound for shoulder pain (negative, of course). [Updated section: Maybe sound waves will help? Ultrasound.]

2020 — Major expansion: Upgraded from a brief dismissal of the topic to a full discussion, from 100 words to 1000. [Updated section: Posture: is frozen shoulder the tip of a misalignment iceberg?]

2020 — Minor upgrade: Added some additional discussion of the implications of Tanya’s story. [Updated section: Case study: an interesting example of a biological X-factor.]

2020 — Major upgrade: Much more thorough exploration of the plausibility and evidence for exploiting the “WOO” that is probably created by steroid injections. [Updated section: Steroids, injected and swallowed.]

2020 — Upgrade: Added quite a bit of additional detail. [Updated section: Whole lotta shakin’ going on: vibration therapy.]

2020 — Minor addition: Expanded on the summary of symptoms just a little, emphasizing the quality and potential severity of the pain. [Updated section: Introduction.]

2020 — Upgraded: Added more information based on a very helpful video that shows “fake” shoulder ROM achieved entirely with good shoulder girdle motion, while the shoulder joint proper remains completely stuck. [Updated section: Diagnosis of Frozen Shoulder: Confirming the diagnosis: classic frozen shoulder symptoms.]

2020 — Editing and more content: Added subsection about passive ROM testing, and did some miscellaneous polishing. [Updated section: Confirm the contribution of functional freezing and sensitization (maybe).]

2020 — Expanded: Added a bunch more specific information about how to recognize sensitization. [Updated section: Confirm the contribution of functional freezing and sensitization (maybe).]

2020 — New chapter: A new chapter about the role of sensitization in frozen shoulder. [Updated section: Sensitization: the foundation of functional freezing.]

2020 — Added detail: Added a good story about my mother-in-law’s broken arm, which nicely illustrates a neurologically mediated ROM lockdown. [Updated section: How does “functional freezing” cause frozen shoulder?]

2020 — New chapter: No notes. Just a new chapter. [Updated section: Opioids too dangerous & ineffective for most cases, but maybe a good idea for a few.]

Archived updates — All updates, including 84 older updates, are listed on another page. ❐

2016 — Publication.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to every reader, client, and book customer for your curiosity, your faith, and your feedback and suggestions, and your stories most of all — without you, all of this would be impossible and pointless.

Writers go on and on about how grateful they are for the support they had while writing one measly book, but this website is actually a much bigger project than a book. PainScience.com was originally created in my so-called “spare time” with a lot of assistance from family and friends (see the origin story). Thanks to my wife for countless indulgences large and small; to my parents for (possibly blind) faith in me, and much copyediting; and to friends and technical mentors Mike, Dirk, Aaron, and Erin for endless useful chats, repeatedly saving my ass, plus actually building many of the nifty features of this website.

Special thanks to some professionals and experts who have been particularly inspiring and/or directly supportive: Dr. Rob Tarzwell, Dr. Steven Novella, Dr. David Gorski, Sam Homola, DC, Dr. Mark Crislip, Scott Gavura, Dr. Harriet Hall, Dr. Stephen Barrett, Dr. Greg Lehman, Dr. Jason Silvernail, Todd Hargrove, Nick Ng, Alice Sanvito, Dr. Chris Moyer, Lars Avemarie, PT, Dr. Brian James, Bodhi Haraldsson, Diane Jacobs, Adam Meakins, Sol Orwell, Laura Allen, James Fell, Dr. Ravensara Travillian, Dr. Neil O’Connell, Dr. Tony Ingram, Dr. Jim Eubanks, Kira Stoops, Dr. Bronnie Thompson, Dr. James Coyne, Alex Hutchinson, Dr. David Colquhoun, Bas Asselbergs … and almost certainly a dozen more I am embarrassed to have neglected.

I work “alone,” but not really, thanks to all these people.

I have some relationship with everyone named above, but there are also many experts who have influenced me that I am not privileged to know personally. Some of the most notable are: Drs. Lorimer Moseley, David Butler, Gordon Waddell, Robert Sapolsky, Brad Schoenfeld, Edzard Ernst, Jan Dommerholt, Simon Singh, Ben Goldacre, Atul Gawande, and Nikolai Boguduk.

Notes

Other joints do freeze like the shoulder, but much less often. For instance, there is such a thing as a frozen hip (see de Sa et al.), but it’s so rare and hard to diagnose that we don’t even know how rare it really is. (Byrd et al. argues that it’s “more common than suggested in the published literature,” but still much rarer than frozen shoulder.) Some other joints in the body can probably freeze to some extent as well — frozen ankle! frozen wrist! — but the shoulder is by far the most prone to it.

There’s also an interesting connection to Dupuytren’s contracture — “frozen hand” disease — which is fairly common and may be more similar than it seems. More on that below.

- Weirdly, musculoskeletal pain is a bit of a backwater, simply because medicine has had much bigger fish to fry, like trying to cure major infectious diseases and so on (see A Historical Perspective On Aches ‘n’ Pains). Medical training is certainly better than the competition, but family doctors lack the skills and knowledge to treat most chronic pain and injury problems, especially the tricky, stubborn ones (see The Medical Blind Spot for Aches, Pains & Injuries). Even sports medicine is only beginning to really get going properly, despite the serious money involved in elite athletics (see Grant et al.).

- Wong CK, Levine WN, Deo K, et al. Natural history of frozen shoulder: fact or fiction? A systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2017 Mar;103(1):40–47. PubMed 27641499 ❐

Evidence from seven reviewed studies suggests that frozen shoulder does not resolve on its own without treatment, contrary to the entrenched conventional wisdom (which isn’t supported by any evidence). On the contrary, what the evidence supports is that frozen shoulder prognosis is highly unpredictable, and may resolve much sooner than average… or not at all.

- Eljabu W, Klinger HM, von Knoch M. Prognostic factors and therapeutic options for treatment of frozen shoulder: a systematic review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2016 Jan;136(1):1–7. PubMed 26476720 ❐ “Spontaneous recovery to normal levels of function is possible.”

- Clement et al. paints quite a grim prognosis, with as many as 40% experiencing “persistent symptoms and restricted movement beyond 3 years,” and a troubling 15% left with “permanent disability.” Fortunately, that’s probably a bit alarmist, and those numbers are supported by citations to only two small old studies. Much more recently, Hand et al. looked at many more cases (223) after about 4 years on average. Although they confirmed that 40% still had symptoms, almost all of them were mild (94%), and “only 6% had severe symptoms with pain and functional loss.”

- Hand C, Clipsham K, Rees JL, Carr AJ. Long-term outcome of frozen shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(2):231–6. PubMed 17993282 ❐ About 15-20% of patients develop the disease in both shoulders.

- Bunker T. Time for a new name for frozen shoulder—contracture of the shoulder. Shoulder & Elbow. 2009;1(1):4–9. PainSci Bibliography 52392 ❐

Bunker believes that capsular contracture only accounts for 5% of all shoulder disease, “and since shoulder disease only affects 15% of the population, then it would be reasonable to suggest that the real incidence of capsular contracture is about 0.75% of the population.”

I will be referencing Bunker’s papers again and again in this tutorial.

- Danaei G, Finucane MM, Lu Y, et al. National, regional, and global trends in fasting plasma glucose and diabetes prevalence since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 370 country-years and 2·7 million participants. Lancet. 2011 Jul;378(9785):31–40. PubMed 21705069 ❐

Almost 10 percent of all adults globally have diabetes and that number is rising fast. Increased obesity and inactivity are the primary causes. Danaei et al. predict an enormous burden of disability and medical costs if the trend continues.

- The rotator cuff interval (space) is a wedge of complex anatomy roughly between the top of the humerus and the clavicle, filled with part of the shoulder joint capsule and some tendons and ligaments. Its “roof” is the coracohumeral ligament, a major structural ligament that the arm hangs from. It contains the subscapular recess, an outpouching of the glenohumeral joint capsule, basically sticking right into the rotator cuff interval. Other notable inhabitants of the interval: the long head of the biceps tendon, and the superior glenohumeral ligament. See Petchprapa et al. [free full text] for extreme detail on all of this.

- Omari A, Bunker TD. Open surgical release for frozen shoulder: surgical findings and results of the release. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(4):353–7. PubMed 11517365 ❐ In this study, the authors treated 75 shoulders over a five-year period. Nine improved without surgery. Of the remainder, 66 improved with manipulation under anaesthesia, but 25 did not and “open surgical release” was attempted with those patients: cutting the shoulder free, basically. And those patients “showed a consistent alteration in the rotator interval and coracohumeral ligament. The rotator interval was obliterated, and the coracohumeral ligament was transformed into a tough contracted band.”

- Pietrzak M. Adhesive capsulitis: An age related symptom of metabolic syndrome and chronic low-grade inflammation? Med Hypotheses. 2016 Mar;88:12–7. PubMed 26880627 ❐

- Neviaser AS, Hannafin JA. Adhesive capsulitis: a review of current treatment. Am J Sports Med. 2010 Nov;38(11):2346–56. PubMed 20110457 ❐

- Kraal T, Lübbers J, van den Bekerom MPJ, et al. The puzzling pathophysiology of frozen shoulders - a scoping review. J Exp Orthop. 2020 Nov;7(1):91. PubMed 33205235 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 51813 ❐ “A state of low grade inflammation, as is associated with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and thyroid disorders, predisposes for the development of frozen shoulder.”

- Huang SW, Lin JW, Wang WT, et al. Hyperthyroidism is a risk factor for developing adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: a nationwide longitudinal population-based study. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4183. PubMed 24567049 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 53252 ❐ “The results of our large-scale longitudinal population-based study indicated that hyperthyroidism is an independent risk factor of developing adhesive capsulitis.”

- Fosbøl EL, Rørth R, Leicht BP, et al. Association of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome With Amyloidosis, Heart~Failure, and Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;74(1):15––23. PainSci Bibliography 52255 ❐

This study is focused on an increased risk of heart failure in carpal tunnel syndrome patients, but, as a musculoskeletal medicine guy, I am more interested in the reverse implication: that CTS is probably partially or entirely triggered by some underlying biology that makes things harder for hearts.

- Bishop JY, Santiago-Torres JE, Rimmke N, Flanigan DC. Smoking Predisposes to Rotator Cuff Pathology and Shoulder Dysfunction: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy. 2015 Aug;31(8):1598–605. PubMed 25801046 ❐

- Ingraham. Smoking and Chronic Pain: We often underestimate the power of (tobacco) smoking to make things hurt more and longer. PainScience.com. 1417 words.

- Smith SP, Devaraj VS, Bunker TD. The association between frozen shoulder and Dupuytren's disease. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(2):149–51. PubMed 11307078 ❐

- Bunker 2009, op. cit.

- Helicobacter pylori was famously hunted down in 1983 by Australian scientists Barry Marshall and Robin Warren. Although its link with ulceration was initially met with much skepticism, science came around relatively quickly — convinced by evidence, just like it’s supposed to work. By the mid-90s it was widely accepted that H. pylori infection causes ulcers, and Marshall and Warren got a Nobel prize in 2005 (acceptance speech).

- A much, much fresher example than the H. Pylori story is the idea that the infamous “plaques” of Alzheimer’s disease are, in fact, a form of immune reaction to an invader — “nets” of sticky protein tendrils intended to stop an infection, but which also cause collateral damage. Really amazing science. See: Have researchers been wrong about Alzheimer’s? A new theory challenges the old story.

- Khan U, Torrance E, Townsend R, et al. Low-grade infections in nonarthroplasty shoulder surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017 Sep;26(9):1553–1561. PubMed 28359693 ❐

This explanation from Arthritis Micropia:

However, other sources contradict this (such as Knobler et al.), or, this review much more recently, which explains: “Over the last 10 years our understanding of the taxonomic and intraspecies diversity of this bacterium has increased tremendously, and with it the realisation that particular strains are associated with skin health while others appear related to disease.”Propionibacterium acnes is a skin bacterium which grows well in an anaerobic (low oxygen) environment. The species populates skin pores and hair follicles and feeds on sebaceous matter. This is a fatty substance produced in glands to keep the skin waterproof. P. acnes is a benign skin bacterium which can help the skin by stopping harmful bacteria getting into the pores.

It was long thought that P. acnes caused spots. This was because the number of P. acnes bacteria increases enormously during puberty, together with the number of spots. Recent research has shown, however, that P. acnes actually helps in the fight against spots. Harmful bacteria cannot get a foothold because the pores and hair follicles are already occupied.

- The Infectious Etiology of Chronic Diseases: Defining the Relationship, Enhancing the Research, and Mitigating the Effects. National Academies Press (US); 2004.

One of the great ironies of this organism is that it is a powerful nonspecific immune stimulant that resides naturally in the skin; its role as an immunostimulant in humans is appreciated when cases of severe acne also develop adjuvant-type arthritis.

Some investigators have gone so far as to suggest that severe acne, by virtue of the nonspecific immunostimulatory effects of P. acnes, might have played a role in natural protection against life-threatening diseases such as malaria and plague. In contrast, the acquired immune response to P. acnes has received little attention in humans.

- Horneff 3, Hsu JE, Voleti PB, O’Donnell J, Huffman GR. Propionibacterium acnes infection in shoulder arthroscopy patients with postoperative pain. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015 Jun;24(6):838–43. PubMed 25979553 ❐

- This is about needles and not what’s in them. The last thing the world needs now is more demonization of vaccinations. So let’s not call it SIRVA! It’s a bullshit term, because it has nothing to do with “vaccination” per se. It should be “shoulder injury related to injection” — SIRI! 😜

- Bancsi A, Houle SKD, Grindrod KA. Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration and other injection site events. Can Fam Physician. 2019 Jan;65(1):40–42. PubMed 30674513 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 52264 ❐

- www.wired.com [Internet]. Zhang S. Why Are Cases of Shoulder Injuries From Vaccines Increasing?; 2019 May 21 [cited 19 Aug 7]. PainSci Bibliography 52265 ❐

- Saleh ZM, Faruqui S, Foad A. Onset of Frozen Shoulder Following Pneumococcal and Influenza Vaccinations. J Chiropr Med. 2015 Dec;14(4):285–9. PubMed 26793041 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 52474 ❐ “Although vaccines are of tremendous importance in the prevention of serious illness, we emphasize the importance of administering them at the appropriate depth and location for each patient.” Indeed.

- Mishra P, Stringer MD. Sciatic nerve injury from intramuscular injection: a persistent and global problem. Int J Clin Pract. 2010 Oct;64(11):1573–1579. PubMed 20670272 ❐

“Sciatic nerve injury from an intramuscular injection in the upper outer quadrant of the buttock is an avoidable but persistent global problem, affecting patients in both wealthy and poorer healthcare systems. The consequences of this injury are potentially devastating. Safer alternative sites for intramuscular injection exist.”Like the shoulder!

- Ascani C, Passaretti D, Scacchi M, et al. Can Adhesive Capsulitis of the shoulder be a consequence of COVID-19? Case series of 12 patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021 May. PubMed 33964424 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 52134 ❐

The authors of this paper acknowledge that their study and data cannot prove a link between COVID and frozen shoulder, but their results were nevertheless very-where-there’s-smoke-there’s-fire. They studied a dozen cases of frozen shoulder that closely followed a COVID infection (out of 120 cases of adhesive capsulitis that came to their clinic). I’m no statistician, but that seems high.

They also describe some strong specific reasons to suspect a pathological connection.

Paper abstract:

We present our series of twelve patients with Adhesive Capsulitis (AC) of the shoulder that developed shortly after COVID-19. We hypothesize that AC may be related to the infectious disease and that both direct and indirect effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection may be involved in its development, as may the sedentary lifestyle forced upon these patients by this disease. Future research will be needed to evaluate the short- and long-term natural history and treatment of these patients as well as to compare them with patients with AC did not occur in concomitance with COVID-19.

- Pietrzak 2016, op. cit.

- Stone-throwing hardly seems like a decisive reproductive advantage. And biologically modern humans were around for tens of thousands of years at least before we were using spears and slings to great effect.

- Littlewood C, Malliaras P, Bateman M, et al. The central nervous system--an additional consideration in 'rotator cuff tendinopathy' and a potential basis for understanding response to loaded therapeutic exercise. Man Ther. 2013 Dec;18(6):468–72. PubMed 23932100 ❐

- This phenomenon would have its roots in local inflammation as well as top-down modulation of movement. This inhibition might even be so basic that it’s regulated largely by spinal reflexes, no brain-imposed inhibition at all.

- Rice DA, McNair PJ. Quadriceps arthrogenic muscle inhibition: neural mechanisms and treatment perspectives. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Dec;40(3):250–66. PubMed 19954822 ❐

- LauraOpstedal.wordpress.com [Internet]. Opstedal L. WTH Happened To My Quads? Arthrogenic Muscle Inhibition Explained; 2019 March 16 [cited 22 Feb 27]. PainSci Bibliography 52376 ❐

- After more than two decades of writing about this stuff, I am no longer surprised to learn about weird knowledge gaps, and it seems plausible to me that AMI is well-known when it occurs in the knee only because the muscles are so huge and vital. Losing 20% of a huge muscle is more obvious than losing 50% of a tiny muscle. Would you know if you lost half of your subscapularis muscle mass? Admit it: you don’t even know how to check! Even for those of us who know how to check, it would be hard to tell, and the loss of mass would have to be dramatic for me to even suspect it. So it could certainly be happening to the rotator cuff muscles without being remotely clear. It’s less likely that the big shoulder movers — biceps, deltoid, triceps — would atrophy without being noticed, but they do not need to be the muscles that are inhibited.

- Bunker 2009, op. cit. “Contemporary arthroscopic studies have shown that only 50% of patients diagnosed as having frozen shoulder actually had visual/tactile evidence of the disease.” Bunker doesn’t cite specific independent sources on this, but he has extensive direct experience and is obviously extremely familiar with the literature. I’m happy to take his word for it.

- Many professionals therapists use it as a basis for presumptive treatment — treating as if a diagnosis is true, to see what happens. Massage therapists in particular are fond of this theory, because it would make their skills much more relevant to the condition. 😃 And they want to help, of course!

- See the appendix at the end of the article, about my wife’s experience with frozen shoulder. Basically, it magically went away when she was seriously injured in a car accident, and then returned when she healed from the worst of her injuries. That does not seem like the natural history of adhesive capsulitis! Of course, the diagnosis could have been wrong in the first place — although it appeared to be a textbook case, misdiagnosis is always a possibility. It’s also possible the accident could have ripped the adhesions apart: a traumatic manipulation without the anesthesia. But this also seems unlikely to me, as it probably requires precise force to break adhesions without also breaking other things — and her shoulder was otherwise uninjured.

- Hollmann L, Halaki M, Haber M, et al. Determining the contribution of active stiffness to reduced range of motion in frozen shoulder. Physiotherapy. 2015 2018/06/19;101:e585. PainSci Bibliography 53197 ❐

- Ingraham. Trigger Points on Trial: A summary of the kerfuffle over Quintner et al., a key 2014 scientific paper criticizing the conventional wisdom about trigger points and myofascial pain syndrome. PainScience.com. 5633 words.

- Duplay, S. De la peri-arthrite scapulo-humerale et ces raideurs de l’epaule qui en sont la consequence. Arch Gen Med. 1872;20:513.

- Codman, E. The shoulder. Boston: Todd. 1934.

- Neviaser J. Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: a study of the pathological findings in periarthritis of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg. 1945; 27:211–22.

- Nagy MT, Macfarlane RJ, Khan Y, Waseem M. The frozen shoulder: myths and realities. Open Orthop J. 2013;7:352–5. PubMed 24082974 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 53682 ❐ Nagy MT, Macfarlane RJ, Khan Y, Waseem M. The frozen shoulder: myths and realities. Open Orthop J. 2013;7:352–5. PubMed 24082974 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 53682 ❐

Neviasier, in 1945, described “adhesive capsulitis” using the term “adhesive” to describe the texture and integrity of the inflamed capsule, which he thought was similar to sticking plaster. The term is also inaccurate, as this condition is not associated with adhesions of the capsule, but rather is related to synovitis and progressive contracture of the capsule.

- Luke TA, Rovner AD, Karas SG, Hawkins RJ, Plancher KD. Volumetric change in the shoulder capsule after open inferior capsular shift versus arthroscopic thermal capsular shrinkage: a cadaveric model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13(2):146–9. PubMed 14997089 ❐

- Binder AI, Bulgen DY, Hazleman BL, Tudor J, Wraight P. Frozen shoulder: an arthrographic and radionuclear scan assessment. Ann Rheum Dis. 1984 Jun;43(3):365–9. PubMed 6742897 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 52089 ❐

There are 152 more footnotes in the full version of the book. I really like footnotes, and I try to have fun with them.

Jump back to:

The introduction

Paywall & purchase info

Table of contents

Top of the footnotes

Paying in your own (non-USD) currency is always cheaper! My prices are set slightly lower than current exchange rates, but most cards charge extra for conversion.

Example: as a Canadian, if I pay $19.95 USD, my credit card converts it at a high rate and charges me $26.58 CAD. But if I select Canadian dollars here, I pay only $24.95 CAD.

Why so different? If you pay in United States dollars (USD), your credit card will convert the USD price to your card’s native currency, but the card companies often charge too much for conversion — it’s a way for them to make a little extra money, of course. So I offer my customers prices converted at slightly better than the current rate.

refund at any time, in a week or a year

call 778-968-0930 for purchase help