The Complete Guide to Chronic Tension Headaches

A detailed, science-based tour of stubborn headache diagnosis and treatment, for both patients and professionals

Almost every second human being has had a tension headache & one in ten have had a migraine, putting headaches in the top 10 most disabling conditions (top 5 for women).

The two main kinds of common headaches are tension-type headaches and migraines. Almost half of the population knows the pain of tension headaches, and one in ten get migraines, and more women — making headaches one of the top 10 most disabling conditions, and the top 5 for women.1 That’s a lot of aching heads.

Migraines are usually worse than tension headaches, but not necessarily: some migraines are quite tame, while “just” a tension headache can be shockingly fierce and stubborn. Some migraines turn out to be monstrous tension headaches.2

Chronic tension headache: how long can they last?

What if you’ve had a tension headache for a week? Maybe many times? Or what if you just have a constant tension headache, indefinitely? All these awful scenarios can still be “just” a tension headache or some other musculoskeletal headache, and most are — but the longer a tension headache lasts, the more likely there’s something else going on.

This tutorial is mostly about chronic tension headaches, but with plenty of comparing and contrasting with migraine and many other kinds of headaches. It’s about troubleshooting unexplained headaches that may or may not have anything to do with “tension.” There’s lots ahead about diagnosis and when to worry about headaches, the multitudinous causes of headaches,3 reviews of all the best and most popular treatment options (rarely the same thing). There are some case studies, some dad jokes, and plenty of “fun facts” and mythbusting along the way.4 Headaches are awful, but they are also interesting!

| Tension Headache | Migraine |

|---|---|

| musculoskeletal pain | neurological “brain ache” |

| mostly less awful | often worse … but not always! |

| usually both sides | usually one side |

| pressure, tightness | throbs with pulse |

| noise sensitivity | light sensitivity |

| few weird symptoms | weirdness standard |

The nature of the beast: what is a “tension” headache?

Is a headache a BRAIN ache? Some of them are. Case courtesy of Dr Bruno Di Muzio, from Radiopaedia.org case 57738.

Kids like to ask “why?” When you answer, they like to ask it again. And again. And again. If you ever try to explain tension headaches to a kid, you’re going to hit a brick wall quickly, because it is not a biologically clear concept. Why do people get tension headaches? Because of stress and, er, tension. But why? Um… I guess, well, tension is painful…

And why is that?

Experts are stumped by this too, because “tension headache” is just a catch-all term for any unexplained headache that isn’t a migraine and doesn’t seem to be scary in any other way. A better name might be musculoskeletal headache, or perhaps just undiagnosed headache, rather than blaming “tension,” which is extremely vague. The moment there’s a better and more specific explanation for a headache than “tension,” it ceases to be a tension headache. But until then…

Most of us know all too well that headaches are strongly linked to stress.5 Stress either causes pain directly and/or it causes other things to go wrong that hurt, usually assumed to be musculoskeletal problems — trouble with bones, joints, and meat.6 But exactly how we get from stress to headache is quite uncertain.

Stress, tension, pain? How stress makes heads ache (maybe)

Does stress cause pain via the mechanism of tension?

Everbody just “knows” that this is true. But this simple causal relationship is surprisingly poorly understood, but many kinds of pain clearly do NOT work this way. But headache may be the only example where it probably does.

Is there such a thing as a pure stress headache, where the only problem is with your feelings? A completely sensory phenomenon, involving no physical stress of any kind? Probably, yes: as if life wasn’t hard enough, we humans have the power to transmogrify emotional distress into discomfort (somatization). If it’s possible for us to feel terrible pain when there’s absolutely nothing actually wrong with us — which it probably is, unfortunately78 — then a headache might be the most routine example of this, probably the most common form of psychosomatic pain, where “headache” almost literally means “painful thinking.”

But it’s more likely there’s usually some kind of intermediate physical step. That is, feelings cause something to happen in the flesh which, in turn, is the actual cause of aching in the head. But what would that be, exactly?

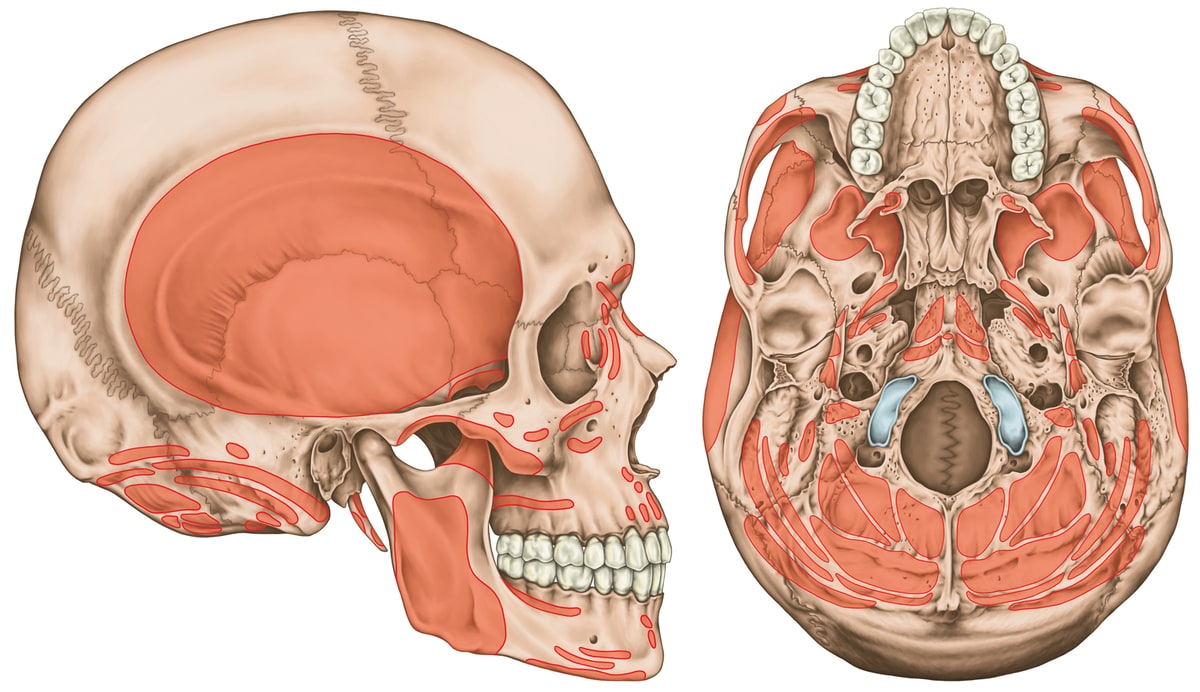

“Muscle tension” is the main suspect — not a well-established fact scientifically, but seemingly obvious to everyone.9 Most of the time, for most people, a “tension headache” feels like muscular tightness around the head, neck, and face, and shoulders, especially sore, stiff suboccipital muscles under the back of the skull, and the jaw muscles, especially in the temple.

Jaw muscles get used heavily. That may lead to some headaches.

Muscle tension is probably inherently uncomfortable and the main mechanism by which stress causes headache, but muscles can also probably get into worse trouble than mere tension. The neck, jaw, and shoulder muscles are routinely sore, full of (hypothetical) trigger points (“muscle knots,” actual knots not included)10 that radiate pain all over your head, and sometimes down into your neck, shoulders and even arms as well.11 These tender spots in muscle are either literally tense (contracted), or they just feel like it,12 which is one of the reasons we call it a “tension” headache. The problem is that these sensitive spots are barely understood, and their role in headache is unconfirmed.

Despite all the scientific uncertainty, treating many unexplained headaches can be as simple as just learning about these “perfect spots” for massage. I will discuss muscle pain much more later in the tutorial.

Muscle attachment areas of the skull… a lot of them, especially on the underside. Most of the muscles on the bottom of the skull are also neck muscles. Click to zoom.

But it’s not all about tension

Feelings of “tightness” could just be a symptom of other kinds of headaches. A lot of unexplained headaches are probably caused not by stress, directly or indirectly, but by other musculoskeletal problems, simpler than the exotic physiology of migraine, but you would be surprised how zany musculoskeletal pain can get. Many headaches are probably cervicogenic headaches (“from the neck”), but even that simple idea has been amazingly controversial.13

Part 2

Diagnosis of Tension Headache

When to worry about a headache (and when not to)

“Well, there’s your problem…”

If only the cause of headache were always this easy! But it’s usually more subtle, and even some dangerous causes can be amazingly hard to diagnose. See also When to Worry About Neck Pain … and when not to!

Safety first, please: severe and strange headaches need medical investigation. There are many types of headaches — literally hundreds of them — and some have serious medical causes. Headaches can be their own problem (primary), or they can be a symptom of something else (secondary). You need to see a doctor, stat, if your headaches are:

- unusually severe, more than 7/10 show

![]()

This is Pain Level 8 as depicted by Allie Brosh in her hilarious article about severe pain, Boyfriend Doesn't Have Ebola. Probably. Pain Level 8 is pretty bad.

- unusually persistent (more than a day at higher pain levels, more than a week at moderate pain levels)

- unusually sudden, a so-called “thunderclap” headache, which comes on in seconds to minutes14 (just as much fun as they sound like)

- unusual in any other way15

- associated with other worrisome symptoms, especially facial numbness16

The worst sneaky common cause of headaches is probably torn vertebral arteries. Headache is the only symptom of up to half of these cases in the first few days, but it is usually a really weird headache. More on this later.

And a headache can be all that and still turn out to be a tension or musculoskeletal headache. So please, don’t panic.

Is headache a symptom of COVID-19? (Or other common infections?)

It’s not one of the “classic” COVID-19 symptoms, but it’s certainly possible — in 8% of cases according to one report,17 14% of cases in another.18 That’s roughly the same percentage of patients suffering from widespread body aching, and so headache is probably mostly just a part of that phenomenon.

The symptoms of most infections are not directly caused by the damage they do to our tissues, especially at first. We cannot feel cells being killed by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, or any other virus; what we feel is our immune system’s reaction to the invasion. One purpose of that reaction is to force us to stay still — also known as rest — mostly by making movement feel difficult and unpleasant. This “sickness behaviour” is a generalized reaction to many kinds of biological threats in all animals.19 It’s quite prominent in COVID-19.20

So why do only 14% of COVID-19 patients get a headache? Some people are more vulnerable to developing headaches, and an infection can expose that vulnerability because cytokines lower our pain threshold dramatically, making everything and anything more likely to hurt. The variation could also be due to the initially infected tissues.

What’s the worst-case scenario for tension headaches?

The best advice in the galaxy applies to unexplained headaches. Even a lot of really serious ones.

As Han Solo said: “I don’t know, I can imagine quite a bit.” In the fall of 2017, I had a mild tension headache for several weeks, almost non-stop (just one piece of my own chronic pain problems). It would surge up to moderate severity in the evenings, and there were a few patches that were impressively bad, but it was the grind of constant pain, regardless of severity, that I think really took its toll on me.

And this is a fairly typical example of the most common worst-case scenario: not especially crippling in any given moment, but still severe and exhausting. The grind is part of the severity of the pain, which anyone with chronic tension headaches can relate to. Here’s what an old friend of mine had to say about it, and he has a lot more experience with that grind:

I find low level chronic pain much worse than infrequent acute pain. It is a weird thing (maybe not for someone with your knowledge base) that I can easily shrug off significant pain like getting kicked in the face in martial arts … but steady low level stuff like headaches mentally breaks me pretty quickly.

I didn’t properly appreciate this until I’d felt it. There is nothing “mild” about mild pain when it just won’t let up. It’s hard for me to imagine what a whole year of that would be like; a couple months was bad enough. As is so often the case, one must live with a problem to really understand it. More and more, I wonder how I could possibly publish a good website about pain if I didn’t also suffer from it. “Lucky” for me, I do have that experience.21

The worst possible tension headaches

Headaches are so common and diverse that nearly anything is possible. Billions of people, hundreds of millions of headaches… somewhere out there, there are people with some truly spectacular headaches. Sky’s the limit.

What if we consider primary tension headache alone? There’s still extraordinary potential awfulness in such a huge population, but there probably are limits: tension headaches probably can’t actually knock someone down and keep them there, assuming there really is nothing else worrisome going on. Even the worst intensity will come in waves, easing with sleep or rest or time; and headaches that drag on for years and decades, effectively permanent, won’t be constantly disabling. Extremes of both intensity and chronicity are possible with tension headache, but probably not both. A headache that is continuously disabling for long periods is almost certainly not just a tension headache.

See the footnotes for three examples, spanning the range from “definitely possible for a tension headache”22 to “it might be possible but a bit unlikely”23 to “there’s probably something else going on here.”24

So the worst average25 case scenario is “just” the “annoyance” of chronic headaches … plus their worst common consequences, insomnia and exercise intolerance, which in turn has even more serious consequences, especially other kinds of pain. People with bad, chronic headaches are in significant long term danger of poor health.

Although tension headaches can be amazingly severe — again, they can be more savage than lesser migraines — even the worst aren’t dangerous in the short term. (This also applies to migraines, even though they can be bad enough to crush your will to live.) The main thing is just to recognize — with expert help — when a headache is not just a headache. Consider the chilling (but entertaining) story of scientist Yvette d’Entremont:

I got the worst headache of my life and it didn’t go away. This horrible ache took residency behind my left eye and refused an eviction notice. I consulted endless doctors and it took eight months to find the first doctor who would start getting my headaches under control …

After a multi-year diagnostic odyssey, Yvette’s headaches proved to be caused by a combination of two medical problems (Ehlers Danlos Syndrome and celiac disease). So, again, odd severe headaches should always be taken seriously.

Tension headache vs. migraine

Tension-type headaches are more common than all other types put together, by a long shot. But heads can ache in many ways. So many ways! You would not believe. And so confirming a headache type can be difficult or impossible.

Tension and migraine headaches are the main primary headaches — headaches that are the main problem, rather than being a mere symptom of some other problem, like dehydration/hangover headaches, which are secondary. But a headache’s primary-ness is only a function of our ignorance of the specific cause. “Primary” headache is really just another way of saying “unexplained” headache. The moment a specific cause for a headache is identified, in a •poof• of nomenclatural smoke, the headache is demoted to secondary, and becomes a symptom of whatever we know to be causing the problem.

Migraines have many distinctive features, because they involve brain function. As mentioned above, although migraines are often severe, the word migraine is not just a way to say “it’s a really bad headache.” A migraine is a different kind of headache. They usually stick to one side of the head (except in kids), typically in front or near the temple. They last for at least a few hours and as long as (ugh!) three days. The pain is related to brain blood vessels, so migraines are often pounding in sync with your pulse (or possibly alpha brain waves—it’s complicated). Light sensitivity is common and can be severe. Migraines may be caused or aggravated by physical exertion, or triggered by foods and smells, most famously (and depressingly) wine and chocolate. And there needs to be a pattern of at least several attacks for an official diagnosis.

And finally, the most distinct feature of migraines, the infamous “aura”: weird visual, auditory, and other neurological disturbances27 that develop over 5-20 minutes and last for about an hour. Migraine auras are a warning sign that a migraine headache may follow, but not all migraines have auras … and not all auras are followed by migraines.

It’s also possible to have a variety of other migraine warning symptoms for up to a day or two beforehand: fatigue, mental fog, neck stiffness, constipation, strong food cravings.

If any of this weird migraine stuff sounds like you, then you probably do not have tension headaches. Or not just tension headaches, at any rate — people who get migraines can also get tension headaches.

Here’s a more detailed version of the tension headaches vs. migraine table:

| Tension Headache | Migraine |

|---|---|

| musculoskeletal pain, especially spreading into the head from the jaw and neck | neurological “brain ache”, formerly classified as a “vascular” headache but no more (“it’s complicated”) |

| mostly less awful, but severe tension headaches are just as bad as any migraine | often worse, but they actually can be milder than tension headaches (or even painless, consisting only of non-pain neurological symptoms) |

| often on both sides | usually just one side |

| feels like pressure, tightness | feels like throbbing with pulse |

| noise sensitivity | light sensitivity and visual disturbances common |

| smell intolerance (osmophobia) never occurs with tension headache | occurs in ~40% of case |

| no weird symptoms, though they can be bad enough to cause malaise | many weird symptoms, particularly sensory disturbances, auras and prodromal symptoms |

Other primary headache types: cluster, exertional, thunderclap, hypnic, and more

“Thunderclap” headaches: exactly what it sounds like, and just as bad. One of the best examples of a distinctive primary headache. Photo by Michał Mancewicz.

There are two major primary headaches, the migraines and the cluster headaches, and then a large “other” category. This section is devoted to those others.

None of these headache types are common.

Cluster headaches are cousins to migraines, but are more severe, distinctive, eye-o-centric, and a hundred times less common. While migraines can be mistaken for tension headaches, cluster headaches cannot: they are just too awful and odd. The pain is almost always around and/or above one eye and/or the temple, and that eye may droop, leak, and swell. Victims often pace miserably, agitated and restless. These headaches occur in clusters of many headaches for a while (and then there’s nothing for weeks, months, or even years).

The other primary headaches (though several of these could also be symptoms of other conditions). Notice how these tend to just be descriptive names — because that’s all we’ve got.

- stabbing headache — nasty intermittent stabbing pains mainly in eye, temple, and side of the head

- cough headaches — caused by coughing (duh), but also straining on the toilet and holding the breath strongly (valsalva maneuver)

- exertional headaches — non-migraine headaches that occur only during/after exercise, and the first time one of these happens it’s critical to make sure it’s not related to a brain bleed

- sex headaches — exactly what it sounds like28

- thunderclap headaches — also exactly what it sounds like, and just as bad (I have personal experience with these)

- hypnic (sleep) headaches — these wake people from sleep

The secondary headaches (when headache is a symptom or complication of something else)

Humans put a surprising number of things in their noses, and have even been known to forget them there. This is a metal nut in the left nasal cavity of a girl. Case courtesy of Dr Maulik S Patel, from Radiopedia case 10514.

Hopefully I don’t need to explain that hangovers can cause headaches. But did you know that your brain might be leaking? Or full of tape worm eggs? Or that there’s a kind of stroke that results in only a headache? Some headache causes are quite sneaky and bizarre.

For instance, long ago a man hid a little wad of marijuana up his nose, and then lost it up there and forgot it for almost twenty years — oops! — until it started causing severe headaches:

Through the years he suffered recurring sinus infections and had trouble breathing out of the right side of his nose. But he didn’t connect the problems to his lost cannabis. It wasn’t until 18 years later — when he was struggling with headaches and had a CT scan of his brain — that doctors finally discovered the petrified pot.

That is a perfect, bizarre example of a “secondary” headache.

A headache that has a clear cause is secondary to that cause, a symptom rather than the disease. And of course there’s a big murky grey zone between primary and secondary headaches.

So obviously almost anything can give you a headache, but here’s some carefully selected examples where the cause of a headache could easily be overlooked or misunderstood.

None of the serious causes of secondary headache are common. Even the most common serious ones are extremely unlikely to be the explanation for any one person’s headache. All possible secondary causes of headaches combined are fairly common, though. They add up to common!

•

Aneurysm, a torn artery in the neck, is the most worrisome common cause of headaches that can actually pass for a tension headache, at least at first. In addition to the large carotid artery, small arteries in the side of the neck supply the brain with blood, the vertebral arteries. These arteries are somewhat vulnerable to being pinched off or even torn. If the artery actually tears, which can cause brain damage due to the loss of blood supply to the brain, it’s called vertebral artery “dissection,” or VAD.

Distrubingly, VAD may only cause neck/head pain — no other symptoms — which is disturbingly little indication of a dangerous injury. It’s not clear how common these pain-only cases are, but it’s at least one in ten in the first day or two.29 As time goes on, the symptoms are likely to get too strong and weird to pass for tension headache. But it is hypochondriac nightmare fuel, because it’s a serious problem that can pass for an ordinary, common one. But it’s not a perfect mimic: the pain is usually severe, one-sided, with an unfamiliar quality (usually throbbing and constrictive). It is an injury, and it probably feels like it if you stop and think about it. For more information, see When to Worry About Neck Pain … and when not to!

•

Anxiety is a potent driver of practically every conceivable kind of pain, but headaches are right at the top of the list (along with chest pain). Even normal stress can do this, but when worries are severe and prolonged, headaches are a super common symptom. Headaches are a standard sideshow to panic attacks.

•

Jaw trouble is strongly linked to headaches (temporomandibular joint syndrome and bruxism, teeth grinding). Jaw pain is dominant in most patients, unlikely to be missed. But, for a few (probably less than 5%) the main symptom is actually headache, and the connection doesn’t get made. I will devote a chapter to the jaw’s role in headache.

Jaw trouble is strongly linked to headaches

•

Eye strain is also strongly linked to headaches. As with jaw trouble, it’s usually obvious that the headache is secondary — but not always.

•

Cerebrospinal fluid leaks — literally leaks in the membrane that wraps your brain and spinal cord — are often subtle, causing mainly headaches and face, neck, and arm pain, although there’s a laundry list of other odd symptoms. The big clue is that these headaches flare when you’re upright. Despite this signature symptom, CSF leaks often go undiagnosed. If you have chronic headaches that usually feel better on your back, and especially if your health feels a bit fragile in general, definitely look into this: Upright Headache? Think CSF Leak! For many patients, just the words “upright headache” will spark a revelation.

•

Temporal arteritis is an inflammation of arteries in the temple, with a lot of symptoms: severe headache, fever, scalp tenderness, jaw pain, vision trouble, and ringing in the ears are all possible symptoms, along with neck pain. It’s almost unheard of in people younger than 50, and it usually occurs in people with other diseases or infections. However, it may be possible to have a relatively minor case bad enough to cause pain but not severe enough to be easily diagnosed.

•

Post-concussion syndrome involves a lot of headaches. Yes, it’s true: a sharp blow to the head can cause headaches! You heard it here first. PCS is “a complex disorder in which various symptoms — such as headaches and dizziness — last for weeks and sometimes months after the injury that caused the concussion.” Post-concussion headaches cannot be directly treated — they are “brain aches” caused by direct trauma to the brain — with the possible exception of exercise.30 Obviously that is not a tension headache, but the pain might lead to tension headaches as a complication, which might partly explain why recovery time from post-concussion syndrome is so notoriously unpredictable.31 And there could be involvement of other tissues in many cases, such as trauma to musculoskeletal structures throughout the head and neck (especially whiplash), causing cervicogenic headache. And so even though the pain of post-concussion syndrome headaches can’t be directly treated, it may come with other types of headache that can be.

•

Drug side effects and withdrawal. Drug side effects are a common sneaky cause of headaches. More surprising is that headaches are a side effect of pain-killers, which seems tragically unfair, like coffee that makes you drowsy. But ironic side effects like this (“paradoxical” effects) are for real, and it’s known as medication-overuse headache (MOH). When you take a lot of pain killers, they may pre-empt the production of your body’s own pain-fighting chemistry, and that can have nasty consequences when you stop taking the drugs, resulting in worse pain than ever. This is part of the phenomenon of the well-known and serious withdrawal symptoms from some drugs; it is a less well-known problem with over-the-counter pain-killers. Given how common analgesic usage is, some people with recurrent headaches are probably suffering from bouts of rebound pain, occurring in the occasional gaps between erratic but generally excessive use of pain killers. Definitely something to watch out for. I will devote a whole chapter to this topic.

Another example of a paradoxical reaction is duloxetine (Cymbalta), an antidepressant often also used for back pain,32 fibromyalgia, neuropathy, and even migraine. Unfortunately, it can also cause headaches — sometimes severe ones.33

Weirdly, nitroglycerin — the explosive and the pills for angina — is also occasionally used as an medicinal ointment or patch for tendinitis. It is allegedly a pain-killer, but definitely headache-causer.34

•

Chronic sinus inflammation is probably a surprisingly common cause of headaches. Acute sinusitis is not subtle, but chronic inflammation from chronic infection or allergies can be surprisingly hard to nail down, and remarkably similar to tension headaches. Or you could have both, because having chronically painful sinuses is stressful!

•

A few other possibilities:

- Ear infections (usually fairly obviously an ear problem)

- Irritation from hats, helmets, goggles, ponytails… and face shields and masks! A minor new hazard in time of COVID-19.35

- Glaucoma (damaged optic nerve, often caused by high eyeball pressure)

- Dehydration is probably an over-hyped cause of headaches (read more below)

- Monosodium glutamate is another over-hyped cause of headaches (read more below)

- There are a few possible causes of headache related to exotic neck problems, like chiari malformation, tethered cord syndrome, and atlantooccipital instability (read more)

- Enemies that are “crushing your head."

Part 3

Causes of Headache

Major factors in so-called tension headaches and other unexplained headaches

Some headaches may not be entirely about the actual head.

This part of the tutorial discusses the causes of headache, but it can also be seen as “diagnosis continued.”

For this topic, diagnosis is hard to separate from etiology (the nature of the beast). In most of my books, I talk about the nature of a problem before I talk about how to confirm the diagnosis. But it’s the other way around here, because you can’t talk about headache causes until it’s clear what kind of headache we’re talking about — and so it seemed important to explain and eliminate a whole bunch of other possibilities first.

And yet even “tension” headache is not one thing, not even remotely. It breaks down into many possible specific causes that make the label of “tension” irrelevant. And every one of thoses causes has distinct diagnostic implications. So this isn’t just about the causes of tension headaches, but the causes of any kind of headache that can’t easily be diagnosed, and digging into them will suggest more diagnostic possibilities.

One of the best examples is using a cervical nerve block — injecting a numbing agent to see if the pain is coming from the neck. If the pain goes away, bingo, you’ve discovered that a neck issue is the cause of your headache — not tension. A nerve block is not a big deal, but a needle deep in the upper neck isn’t a trivial procedure either. For most patients, it will never even be on the radar as an option.

So cause and diagnosis are basically impossible to separate with headache. Every major cause needs its own diagnostic approach. So we’ll continue the diagnosis/cause discussion with the mother of all plausible, common “tension” headache causes: the cervicogenic or neck-powered headache.

From the neck or not? The cervicogenic headache debate

“Jane” was a nurse, just 23 years old, and she’d had the same headache since she was 20, a constant throb on the right side of her head. She worked in a radiology department, and had to wear a lot of lead aprons. She blamed those heavy aprons for the headache, always dragging her down.

She had an acutely sensitive spot on the back right side of her neck, though, just a handful of inches south of the pain. And she had more pain every time she turned her neck that way…

END OF FREE INTRODUCTION

Purchase full access to this tutorial for USD$1995. Continue reading this page immediately after purchase. See a complete table of contents below. Most content on PainScience.com is free.?

Almost everything on this website is free: about 80% of the site by wordcount, or 95% of the bigger pages. This page is only one of a few big ones that have a price tag. There are also hundreds of free articles. Book sales — over 74,500 since 2007?This is a tough number for anyone to audit, because my customer database is completely private and highly secure. But if a regulatory agency ever said “show us your math,” I certainly could! This count is automatically updated once every day or two, and rounded down to the nearest 100. Due to some oddities in technology over the years, it’s probably a bit of an underestimate. — keep the lights on and allow me to publish everything else (without ads).

Q. Ack, what’s with that surprise price tag?!

A. I know it can make a poor impression, but I have to make a living and this is the best way I’ve found to keep the lights on here.

Paying in your own (non-USD) currency is always cheaper! My prices are set slightly lower than current exchange rates, but most cards charge extra for conversion.

Example: as a Canadian, if I pay $19.95 USD, my credit card converts it at a high rate and charges me $26.58 CAD. But if I select Canadian dollars here, I pay only $24.95 CAD.

Why so different? If you pay in United States dollars (USD), your credit card will convert the USD price to your card’s native currency, but the card companies often charge too much for conversion — it’s a way for them to make a little extra money, of course. So I offer my customers prices converted at slightly better than the current rate.

refund at any time, in a week or a year

call 778-968-0930 for purchase help

| company | PainScience.com |

|---|---|

| owner | Paul Ingraham |

| contact | 778-968-0930 |

| refunds | 100%, no time limit +Customers are welcome to ask for a refund months after purchase — I understand that it can take time to decide if information like this was worth the price for you. |

| more info | policies page ❐ |

| payments |

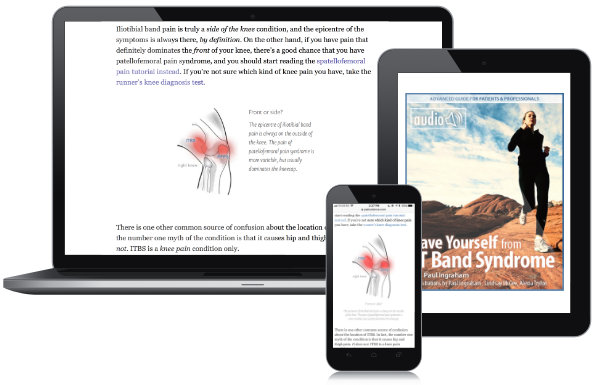

- What do you get, exactly? An online tutorial, book-length (53 chapters). Free updates forever, read on any device, and lend it out. E-book only! MORE

- Secure payment takes about 2 minutes. No password or login: when payment is confirmed, you are instantly granted full, permanent access to this page.MORE

- Collect them all. Get an “e-boxed” set of all 10 PainScience.com tutorials, ideal for pros … or patients with a lot of problems.MORE

Q. What am I buying? Is there an actual paper book?

A. Payment unlocks access to 43 more chapters of what is basically a huge webpage. There is no paper book — I only sell book-length online tutorials. This format is great for instant delivery, and many other benefits “traditional” e-books can’t offer, especially hassle-free lending and updates. You get free lifetime access to the always-current “live” web version (and offline reading is easy too).

Read on any device. Lend it out. New editions free forever.

Q. I just don’t like reading on the computer! Is there any way around that?

A. The design and technology of the book is ideal for reading on tablets and smart phones. You can also print the book on a home printer.

Q. Can I lend the tutorial out?

A. Yes! Feel free to lend your tutorial: I do not impose silly lending limits like with most other ebooks. No complicated policies or rules, just the honour system! You buy it, you can share it. You can also give it as a gift.

Q. Is it safe to use my credit card on your website?

A. Literally safer than a bank machine. Payments are powered by Stripe, which has an A+ Better Business Bureau rating. Card info never touches my servers. It’s easy to verify my identity and the legitimacy of my business: just Google me [new tab/window].

Q. I can really get a refund at any time?

A. Yes. All PainScience.com ebooks have a lifetime money-back guarantee.

Q. Why do you ask for contact information?

A. To prevent fraud and help with order lookups. You aren’t “subscribing” to anything: I never send email to customers except to confirm purchases.

Q. Can I buy this anywhere else? Amazon?

A. Not yet. Maybe someday.

See the “fine print page” for more about security, privacy, and refunds. No legalese, just plain English.

Save a bundle on a bundle

The e-boxed set is a bundle of all 10 book-length tutorials for sale on PainScience.com: 10 books about 10 different common injuries and pain problems. All ten topics are (all links open free intros in a new tab/window): muscle strain, muscle pain, back and neck pain, two kinds of runner’s knee (IT band syndrome and patellofemoral pain), shin splints, plantar fasciitis, and frozen shoulder. (Headache coming soon, fall of 2019.)

Most patients only need one book, because most patients have only one problem. But the set is ideal for professionals, and some keen patients do want all of them, for the education, and for lending to friends and family. And, of course, you do get a substantial discount for the bulk purchase. But no rush—complete the set later, minus the price of any books already bought. More information and purchase options.

Paying in your own (non-USD) currency is always cheaper! My prices are set slightly lower than current exchange rates, but most cards charge extra for conversion.

Example: as a Canadian, if I pay $19.95 USD, my credit card converts it at a high rate and charges me $26.58 CAD. But if I select Canadian dollars here, I pay only $24.95 CAD.

Why so different? If you pay in United States dollars (USD), your credit card will convert the USD price to your card’s native currency, but the card companies often charge too much for conversion — it’s a way for them to make a little extra money, of course. So I offer my customers prices converted at slightly better than the current rate.

refund at any time, in a week or a year

call 778-968-0930 for purchase help

How can you trust this information about headache?

I apply a MythBusters approach to health care (without explosives): I have fun questioning everything. I don’t claim to have The Answer for tension headache. When I don’t know, I admit it. I read scientific journals, I explain the science behind key points (there are more than 210 footnotes here, drawn from a huge bibliography), and I always link to my sources.

For instance, there’s good evidence that educational tutorials are actually effective medicine for pain.?Dear BF, Gandy M, Karin E, et al. The Pain Course: A Randomised Controlled Trial Examining an Internet-Delivered Pain Management Program when Provided with Different Levels of Clinician Support. Pain. 2015 May. PubMed 26039902 ❐ Researchers tested a series of web-based pain management tutorials on a group of adults with chronic pain. They all experienced reductions in disability, anxiety, and average pain levels at the end of the eight week experiment as well as three months down the line. The authors concluded: “While face-to-face pain management programs are important, many adults with chronic pain can benefit from programs delivered via the Internet, and many of them do not need a lot of contact with a clinician in order to benefit.” Good information is good medicine!

And I’ve worked hard for many years to provide the best information about tension headaches available anywhere — not just more of it, but better.

But there are limits to current scientific knowledge about headache. Not everyone can be helped. The goal of this tutorial is to help you navigate the maze of medical uncertainty and contradictions, and the many possible causes.

This tutorial does not give you a magic bullet for headaches, but it does provide readers with many ideas and “upgrades” to their approach to the problem. Most people who think they’ve “tried everything” have not actually tried everything. With some more informed and rational experimentation, many cases can improve from being disabling to at least manageable.

All of that is hopefully worth more than several sessions of physical therapy, at a fraction of the cost.

Paying in your own (non-USD) currency is always cheaper! My prices are set slightly lower than current exchange rates, but most cards charge extra for conversion.

Example: as a Canadian, if I pay $19.95 USD, my credit card converts it at a high rate and charges me $26.58 CAD. But if I select Canadian dollars here, I pay only $24.95 CAD.

Why so different? If you pay in United States dollars (USD), your credit card will convert the USD price to your card’s native currency, but the card companies often charge too much for conversion — it’s a way for them to make a little extra money, of course. So I offer my customers prices converted at slightly better than the current rate.

refund at any time, in a week or a year

call 778-968-0930 for purchase help

Part 3.2

Appendices

Related Reading

- Deep Cervical Flexor Training for Neck Pain — “Core” strengthening for the neck is even less evidence-based than core-strengthening for back pain

- When to Worry About Neck Pain … and when not to! — Red flags versus non-scary possible explanations for bad neck pain

- What Happened To My Barber? — Either atlantoaxial instability or vertebrobasilar insufficiency causes severe dizziness and vomiting after massage therapy, with lessons for health care consumers

- Neck Pain, Submerged! — The story of my curious experiment with dunking severe chronic neck pain

- Spinal Subluxation — Can your spine be out of alignment? Chiropractic’s big idea has been misleading patients for more than a century

- Stretching Injury — How I almost ripped my own head off! A cautionary tale about the risks of injury while stretching

- The Complete Guide to Neck Pain & Cricks — An extremely detailed guide to chronic neck pain and the disturbing sensation of a “crick”

- Sensitization in Chronic Pain — Pain itself can change how pain works, resulting in more pain with less provocation

- Does Craniosacral Therapy Work? — Craniosacral therapists make big promises, but their methods have failed to pass every fair scientific test of efficacy or plausibility

- 38 Surprising Causes of Pain — Trying to understand pain when there is no obvious explanation

- Three “perfect spots” for massage that are relevant to headache:

- Massage Therapy for Tension Headaches — Perfect Spot No. 1, in the suboccipital muscles of the neck, under the back of the skull.

- Massage Therapy for Bruxism, Jaw Clenching, and TMJ Syndrome — Perfect Spot No. 7, the masseter muscle of the jaw

- Massage Therapy for Upper Back Pain — Perfect Area No. 11, the erector spinae muscle group of the upper back

What’s new in this guide?

This article was originally published in 2004, evolved slowly for a decade. By 2013 I upgraded it to be a book-scale guide, but still free. In 2016 I got more serious about updating it, and also started diligently logging updates for the first time. It was finally launched as a full-blown book in 2019.

Regular updates are a key feature of PainScience.com tutorials. As new science and information becomes available, I upgrade them, and the most recent version is always automatically available to customers. Unlike regular books, and even e-books (which can be obsolete by the time they are published, and can go years between editions) this document is updated at least once every three months and often much more. I also log updates, making it easy for readers to see what’s changed. This tutorial has gotten 74 major and minor updates since logging got properly consistent in 2016 (and there have also been countless minor tweaks and touch-ups).

2024 — Added detail: Added some conspicuously missing detail about how cinook headaches work. [Updated section: Can weather cause headaches?]

2024 — New section: No notes. Just a new chapter. [Updated section: Can weather cause headaches?]

2023 — Minor update: Added more detail about occipital neuralgia. [Updated section: From the neck or not? The cervicogenic headache debate.]

2023 — New section: No notes. Just a new chapter. [Updated section: More detail (much more) about that 'spines look normal in headache patients' study.]

2023 — Minor update: Discussed the special case of occipital neuralgia. [Updated section: From the neck or not? The cervicogenic headache debate.]

2023 — New chapter: No notes. Just a new chapter. [Updated section: Green light therapy.]

2022 — Science update: Added headache as a side effect of Duloxetine. [Updated section: The secondary headaches (when headache is a symptom or complication of something else).]

2022 — Trivial update: A trivial update, but fun, using ice cream headaches as an interesting example of referred pain that is directly relevant to headache. [Updated section: From the neck or not? The cervicogenic headache debate.]

2021 — New red flag: Added “facial numbness,” based on Ugradar et al. [Updated section: Diagnosis of Tension Headache: When to worry about a headache (and when not to).]

2021 — Science update: Updated the chapter with a citation to an important new study showing that there are no obvious neck abnormalities in headache patients. [Updated section: From the neck or not? The cervicogenic headache debate.]

2021 — New chapter: Adapted from the recent blog post, with some substantive extra speculation about the plausibility of a tight frenulum causing headaches. [Updated section: Can your tongue cause headaches?]

2021 — Proofreading: First top-to-bottom proofreading for this book since launch, catching many minor erros that crept in doing about a dozen updates over the last year and half.

2021 — Minor polishing: A little editorial polish, and a bit of elaboration about the role of psychotropic effects. [Updated section: The cannabinoids: marijuana and hemp, THC and CBD — “it’s complicated!”.]

2020 — New section: No notes. Just a new chapter. [Updated section: Sinus irritation and irrigation.]

2020 — New section: No notes. Just a new chapter. [Updated section: Smoking.]

2020 — New content: Added coat-hangar pain from orthostatic hypotension to the collection of more exotic types of cervicogenic headache. [Updated section: More exotic cervicogenic headaches.]

2020 — Science update: Cited a nail-in-coffin 2020 study of dry needling for neck pain. [Updated section: Massage, self-massage, and other trigger point therapies for headache.]

2020 — Science update: Added more detail and citations about headaches caused by physical irritation around the head, including (sigh) personal protective equipment like face masks. [Updated section: Hats off! Eliminate minor sources of physical stress that cause headache.]

2020 — New content: Added a substantial new sub-section, “Trigger points, schmigger points: the many other kinds of muscle injury and dysfunction.” [Updated section: More exotic cervicogenic headaches.]

2020 — COVID-19 update: Added information about headaches as a symptom of COVID-19. [Updated section: Diagnosis of Tension Headache: When to worry about a headache (and when not to).]

Archived updates — All updates, including 65 older updates, are listed on another page. ❐

2004 — Publication.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to every reader, client, and book customer for your curiosity, your faith, and your feedback and suggestions, and your stories most of all — without you, all of this would be impossible and pointless.

Writers go on and on about how grateful they are for the support they had while writing one measly book, but this website is actually a much bigger project than a book. PainScience.com was originally created in my so-called “spare time” with a lot of assistance from family and friends (see the origin story). Thanks to my wife for countless indulgences large and small; to my parents for (possibly blind) faith in me, and much copyediting; and to friends and technical mentors Mike, Dirk, Aaron, and Erin for endless useful chats, repeatedly saving my ass, plus actually building many of the nifty features of this website.

Special thanks to some professionals and experts who have been particularly inspiring and/or directly supportive: Dr. Rob Tarzwell, Dr. Steven Novella, Dr. David Gorski, Sam Homola, DC, Dr. Mark Crislip, Scott Gavura, Dr. Harriet Hall, Dr. Stephen Barrett, Dr. Greg Lehman, Dr. Jason Silvernail, Todd Hargrove, Nick Ng, Alice Sanvito, Dr. Chris Moyer, Lars Avemarie, PT, Dr. Brian James, Bodhi Haraldsson, Diane Jacobs, Adam Meakins, Sol Orwell, Laura Allen, James Fell, Dr. Ravensara Travillian, Dr. Neil O’Connell, Dr. Tony Ingram, Dr. Jim Eubanks, Kira Stoops, Dr. Bronnie Thompson, Dr. James Coyne, Alex Hutchinson, Dr. David Colquhoun, Bas Asselbergs … and almost certainly a dozen more I am embarrassed to have neglected.

I work “alone,” but not really, thanks to all these people.

I have some relationship with everyone named above, but there are also many experts who have influenced me that I am not privileged to know personally. Some of the most notable are: Drs. Lorimer Moseley, David Butler, Gordon Waddell, Robert Sapolsky, Brad Schoenfeld, Edzard Ernst, Jan Dommerholt, Simon Singh, Ben Goldacre, Atul Gawande, and Nikolai Boguduk.

Notes

- Stovner L, Hagen K, Jensen R, et al. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007 Mar;27(3):193–210. PubMed 17381554 ❐ “Globally, the percentages of the adult population with an active headache disorder are 46% for headache in general, 11% for migraine, 42% for tension-type headache and 3% for chronic daily headache. Our calculations indicate that the disability attributable to tension-type headache is larger worldwide than that due to migraine. On the World Health Organization's ranking of causes of disability, this would bring headache disorders into the 10 most disabling conditions for the two genders, and into the five most disabling for women.”

- Many people assume “migraine” is just a word for a really bad headache, and some people even dramatically boast about the severity of tension headaches by calling them “migraines.” But a migraine is definitely a different kind of animal than an ordinary headache. If you can walk around talking about the fact that you have a migraine, you probably don’t have a migraine. Although they can be tolerable in their early stages, and some can even be surprisingly mild, as a general rule they are much more serious than the worst tension headaches. Most migraines will have their victims flat on their backs in a darkened room.

- There are literally hundreds of defined types of headaches, based on a stupendous variety of known causes, and plenty more than that are based only on a distinct pattern of symptoms.

- Does dehydration cause headaches? How about MSG? Is red wine a headache “trigger”? If tension is the problem, why don’t muscle relaxants work? Do you really need a mouth guard for your clenching and grinding? All this and more will be discussed.

- Martin PR. Stress and Primary Headache: Review of the Research and Clinical Management. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016 Jul;20(7):45. PubMed 27215628 ❐ “…although some researchers have questioned whether stress can trigger headaches, overall, the literature is still supportive of such a link.”

- As opposed to the neurological “brain ache” of migraine. Or the pathological and traumatic causes of some other headaches (like inflamed arteries, brain damage, drug side effects, and so on). There will be much more about other possible causes of headaches below.

- Espay AJ, Aybek S, Carson A, et al. Current Concepts in Diagnosis and Treatment of Functional Neurological Disorders. JAMA Neurol. 2018 09;75(9):1132–1141. PubMed 29868890 ❐

- Truly pure psychosomatic pain is probably a real phenomenon, but it’s not as clear as it should be. The strange-but-true phenomenon of functional neurological disorders is well-studied: seizures, paralysis, blindness, and other neurological symptoms in the absence of any neurological disease (see Espay et al. for a scholarly source, or this more accessible talk: Suzanne O'Sullivan @ 5x15 — The reality of imaginary illness

![]() 19:30). If we can paralyze ourselves with our minds, we can probably make ourselves hurt too.

19:30). If we can paralyze ourselves with our minds, we can probably make ourselves hurt too. - The closest thing to persuasive evidence of a link between headache and muscular tension is a 1991 survey of headache patients (see Lebbink et al.) which found quite a strong link: much higher prevalence of neck muscle tension in headache sufferers especially, plus other links. More about these results later.

- So-called “muscle knots” — AKA trigger points — are small unexplained sore spots in muscle tissue associated with stiffness and soreness. No one doubts that they are there, but they are unexplained and controversial. They can be surprisingly intense, cause pain in confusing patterns, and they grow like weeds around other painful problems and injuries, but most healthcare professionals know little about them, so misdiagnosis is epidemic.

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Simons D, Cuadrado ML, Pareja J. The role of myofascial trigger points in musculoskeletal pain syndromes of the head and neck. Current Pain & Headache Reports. 2007 Oct;11(5):365–72. PubMed 17894927 ❐

This review of the scientific literature, unfortunately, has little scientific literature to review: not much research has been done on the relationship between trigger points and neck pain, and — as is so often the case in musculoskeletal health care — “additional studies are needed.” However, the authors suggest that “it seems that the pain profile of neck and head syndromes may be provoked referred pain from TrPs in the posterior cervical, head, and shoulder muscles” and that there is some evidence “that both tension headache and migraine are associated with referred pain from trigger points.”

- This is a bit sneaky of me, a convenient dodge around the controversy about the nature of trigger points. If the feeling of tension either is a literal contraction, or it just feels that way, I’ve covered all my bases. My money is on literal contraction, but I realize that there’s a lot of scientific uncertainty about that. The subjective sensation of contraction and tightness, however, is indisputable: most of the human race knows that feeling, and doesn’t hesitate to describe it like it’s a contraction. And the simplest explanation for the sensation would probably be that trigger points hurt even if they aren’t actually little contractions, and our brains interpret “uncomfortable movement” as “tightness.” I go into considerable detail about the sensation of tightness in another article: You’re Really Tight: The three most common words in massage therapy don’t mean much.

- Bogduk N, Govind J. Cervicogenic headache: an assessment of the evidence on clinical diagnosis, invasive tests, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2009 Oct;8(10):959–68. PubMed 19747657 ❐ “Although the International Headache Society recognises this type of headache as a distinct disorder, some clinicians remain sceptical.” I’ll return to this topic in more detail later in the tutorial.

- Devenney E, Neale H, Forbes RB. A systematic review of causes of sudden and severe headache (Thunderclap Headache): should lists be evidence based? J Headache Pain. 2014;15:49. PubMed 25123846 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 53381 ❐ Thunderclap headaches have literally dozens of possible causes, some scary, some not so scary. The classic scary cause is brain bleeding (mostly subarachnoid hemorrhages), and it’s important to rule this out … and in many cases it is ruled out. Most cases are never explained and never amount to anything. And then there are the cases caused by eating extremely hot chili peppers. “What could possibly go wrong?” Here’s the news story, and the case report in the British Medical Journal.

- Severe throbbing or constrictive neck and/or head pain may be the only symptom of an artery tear (see Arnold, Kerry, Maruyama) with a high risk of a stroke, but it is almost always a strange pain: Arnold et al. reported that most patients “considered the pain to be unique and unusual compared with previously experienced headache or neck pain episodes. Nevertheless, pain was often interpreted initially as migraine or musculoskeletal in nature by the patient or the treating doctor.” See scary causes of neck pain for more detailed red flag information about this.

- Facial numbness is routinely a sign of a dangerous cancer or infection (see Ugradar) — please always take this symptom seriously! Otherwise, I am referring to weakness, disturbed vision, or any other neuro-ish symptom. Obviously it’s an emergency if you detect any of the big-three stroke signs: face drooping, arm weakness, speech difficulty.

- Lei S, Jiang F, Su W, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients undergoing surgeries during the incubation period of COVID-19 infection. EClinicalMedicine. 2020 2020/04/06. PainSci Bibliography 52605 ❐

- Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Accessed 2020-04-06.

- Ingraham. Chronic, Subtle, Systemic Inflammation: One possible sneaky cause of puzzling chronic pain. PainScience.com. 22580 words.

- This virus seems to provoke more cytokine production than, say, the common cold, and it’s the cytokines that primarily cause the symptoms of “sickness behaviour.” It’s also probably prone to it because it’s a more serious infection — they call it the “novel” coronavirus because it’s new to us, a virus too different from other coronaviruses for our immune system to have any experience with it.

- I had always been “prone” to aches and pains, which is really why I started this website. But in 2015 I graduated to the pain big leagues: serious chronic pain, fatigue, and exercise intolerance plus many other bizarre symptoms, all unexplained, making me a classic fibromyalgia patient. You can read my chronic pain story on Substack: Project Try Everything: A 2-year mission to truly “try everything” to recover from unexplained pain & illness.

- Alan’s headaches are nasty by most people’s standards, but still well within the realm of possibility for tension headaches. He has a low-grade dull throb in the back of his head almost all the time. It usually worsens throughout the day, but he can still work and play through the fog of discomfort. Roughly weekly, he has a flare-up of pain intense enough to stop normal activity; he could still function in an emergency, but he usually just goes to bed early and it’s back to the dull throb in the morning, like a mild hangover.

- Judith’s headaches are bad enough for their nature to be ambiguous: can a tension headache really be this bad? It is possible, but at this level you do have to start wondering if there’s more going on. Judith has pain as constant as Alan’s but more intense: it’s almost always hard for her to think clearly, hard to speak and make normal facial expressions, hard to sleep and exercise — some days she can, some she can’t. She can usually muddle through at work, but she takes all her sick days, usually to accommodate her occasional episodes, which are as harsh as any migraine she’s ever heard of (but without classic migraine symptoms), until she regresses to her miserable mean.

- Aaron’s headaches are too severe not to strongly suspect something more than “tension.” Like Judith, his pain is substantial and constant and has been for a long time, but he also has severe episodes that develop rapidly, and are so frequent and disabling that he can’t hold down a normal job, so he’s become erratically self-employed and financially stressed. He almost never can sleep or exercise properly, and so he feels like he’s aging rapidly, and is starting to develop widespread aches and pains. Theoretically all of this could still be “just” a tension headache, but it would have to be very rare.

- Not the very worst possible. In this reckoning, we trim off the extreme outliers, and just consider the average of all other cases that would be considered severe.

- Zanchin G, Dainese F, Trucco M, et al. Osmophobia in migraine and tension-type headache and its clinical features in patients with migraine. Cephalalgia. 2007 Sep;27(9):1061–1068. PubMed 17681021 ❐

- Seeing shapes, bright spots, flashes. Hearing noises or music. Jerking or twitching. Pins and needles in an arm or leg. Trouble speaking. Just about anything hallucinatory or brain-disturbed. People with migraine auras sometimes think they are having a stroke.

- “Not tonight, honey, you’ll give me a headache.”

Headache-only VAD might be anywhere from 10 and 50% of cases. The uncertainly is probably because it matters when you ask: the symptoms can evolve over several days, as with any injury. Arnold 2006, Kerry 2009, and Maruyama 2012 all propose lower numbers. Bogduk, a particularly expert source cited a lot in this guide, goes much higher:

Sixty percent of patients with aneurysms of the vertebral artery or the internal carotid artery present with headache as the sole feature. Within a matter of a few days, aneurysms typically declare themselves by the onset of neurovascular features. However, during this period, the headache may be misdiagnosed as common cervicogenic headache, unless the practitioner is alert to the possibility of aneurysm.

- Leddy JJ, Haider MN, Ellis M, Willer BS. Exercise is Medicine for Concussion. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2018 Aug;17(8):262–270. PubMed 30095546 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 52267 ❐

- More from the Mayo Clinic resource page on post-concussion syndrome: “In most people, post-concussion syndrome symptoms occur within the first seven to 10 days and go away within three months, though they can persist for a year or more.”

- Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Systemic Pharmacologic Therapies for Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Apr;166(7):480–492. PubMed 28192790 ❐ No medication is particularly effective for most back pain, but Duloxetine did better than any other pharmacotherapy in this review.

- Anwari JS, Hazazi AA. Another cause of headache after epidural injection. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2015 Apr;20(2):167–9. PubMed 25864071 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 52033 ❐ Although this appears to be a case study about epidural injection complications, the mechanism of the headache was ultimately found to be “Duloxetine induced syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) causing severe hyponatremia.” Hyponatremia is when your blood has gotten too watery, your electrolytes too diluted.

- The allegedly active ingredient is actually nitric oxide, which nitroglycerin is quickly converted to in the human body, and it may have anti-inflammatory and connective-tissue-building effects in addition to the powerful vasodilation it’s best known for. There are two pretty decent trials of this (which doesn’t sound like much, but it’s better than we get for most obscure treatments). Paoloni et al. reported a respectable benefit for tendinitis way back in 2004, but also quite a few headaches. In 2024, Kirwan et al. found no benefit at lower dosages … but still saw headaches! I review nitro as a tendinitis treatment in detail in my guide to Achilles tendinitis

- Jy Ong J, Bharatendu C, Goh Y, et al. Headaches Associated with Personal Protective Equipment - A Cross-sectional Study Amongst Frontline Healthcare Workers During COVID-19 (HAPPE Study). Headache. 2020 Mar. PubMed 32232837 ❐ This is just a survey of nurses who already had a headache problem, who “either ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ that the increased PPE usage had affected the control of their background headaches.” There’s more substantive evidence that I will discuss below.

There are 183 more footnotes in the full version of the book. I really like footnotes, and I try to have fun with them.

Jump back to:

The introduction

Paywall & purchase info

Table of contents

Top of the footnotes

Paying in your own (non-USD) currency is always cheaper! My prices are set slightly lower than current exchange rates, but most cards charge extra for conversion.

Example: as a Canadian, if I pay $19.95 USD, my credit card converts it at a high rate and charges me $26.58 CAD. But if I select Canadian dollars here, I pay only $24.95 CAD.

Why so different? If you pay in United States dollars (USD), your credit card will convert the USD price to your card’s native currency, but the card companies often charge too much for conversion — it’s a way for them to make a little extra money, of course. So I offer my customers prices converted at slightly better than the current rate.

refund at any time, in a week or a year

call 778-968-0930 for purchase help