Can Massage Therapy Cause Nerve Damage?

It is possible, but hard to do, rare, and the damage is usually minor

It is possible to damage nerves with massage — but it’s rare, and rarely serious. Massage-induced nerve trauma is not something we need to worry about … but it’s a common concern anyway, driven by excessive “nerve fear” in our society.1 Which is why I get a lot of questions like this one:

One thing that helps sometimes when my neck pain gets excruciating is to really dig my fingers hard into a couple of muscle knots in the back of the neck (not right on the spine but off to each side, below the occipitals), or to use a Thera Cane to do the same thing. Is there any chance of causing nerve damage from so much pressure?

reader Peter Spaeth, Boston

Digging “hard” into the neck isn’t entirely safe, but the modest risks have nothing to do with damaging “nerves” in that location. You might cause some bruising and perhaps make the neck pain worse rather than better. But the nerves? As long as we’re talking about the back of the neck, they are almost perfectly safe, even from the most masochistic self-massage.

In this article, I’ll discuss the physical protection that most nerves have and their inherent resilience of nerves — they aren’t fragile. Despite all that, there isn’t zero risk to nerves, and extra caution is needed with any kind of massage tool, with unusual intense massage, with stretch, and/or some specific areas. I will talk about a few of the more exposed nerves around the body (“endangerment” sites).

An obnoxious, silly stereotype? Yes. But a totally relatable one? Also yes.

What about the notorious vagus nerve? I will explain why there’s no plausible risk of damaging the vagus, or “stimulating” it in a harmful way — although there is other nearby anatomy that is somewhat dangerously vulnerable.

And I’ll share an embarrassing cautionary tale: I did cause a nerve injury once in my ten years working as a professional massage therapist. I still feel bad! I guess I’ll probably never stop.

EXCERPT This article is an adapted excerpt from my neck pain book. The same question is also addressed as a common question about strong massage in my muscle pain book.

Why nerves are not very vulnerable to massage

It is nearly impossible to damage your nerves with respectful massage therapy or sane self-massage, because:

- Nerves are mostly padded well by other tissues.

- Healthy nerves are not fragile, and are no more likely to be damaged by sensible pressures than muscle tissue, blood vessels, or tendon.

- If threatened with trauma from pressure or tension, nerves produce ample warning sensations that will stop any sensible person before much harm is done. You are not much likelier to abuse a nerve than you are to poke yourself too hard in the eye.

There is a bit more risk if you’re being massaged, or if you are self-massaging so with a tool or method that makes it easier to accidentally apply too much pressure too quickly (before you sense the danger). But still not much risk.

Larger nerves are mostly protected

The larger nerves and nerve roots are mostly well shielded by skin, fat, muscle, and bone. Smaller nerves are probably technically more fragile, but much less of a concern otherwise.2 For instance, it’s extremely unlikely that you could harm yourself by massaging in the location Peter asked about — on the back of the neck, beside the spine — because the only prominent nerves in the back of the neck are the nerve roots (bundles of nerve tissue that emerge from between each pair of vertebrae). The nerve roots are buried under a thick layer of sturdy paraspinal musculature, at least a centimetre or two deep.

Not all nerves are well-protected, of course…

Endangerment, Will Robinson!

There are a few places in the body where nerves are more exposed and can be injured by stronger pressures. All of these sites are familiar to any well-trained massage therapist, and weirdly known as “endangerment” sites — but the endangering is minimal even in these locations. Mostly they are just “unpleasantness sites.” They are not places most people want massage in the first place.

Here are all of the commonly cited endangerment sites (nerves highlighted):

| anatomic location (plain English) | potentially vulnerable anatomy |

|---|---|

| Anterior Triangle of the Neck (throat) | carotid artery, jugular vein, vagus nerve; under sternocleidomastoid |

| Posterior Triangle of the Neck (side of the throat) | nerves of the brachial plexus, proximal; brachiocephalic artery; subclavian artery & vein |

| Axillary Area (armpit) | brachial artery, axillary vein & artery, cephalic vein; nerves of brachial plexus, distal |

| Medial Epicondyle, Humerus (inside elbow) | ulnar nerve |

| Lateral Epicondyle, Humerus (outside elbow) | radial nerve |

| Umbilicus region (belly) | descending aorta & abdominal aorta |

| lateral 12th rib (lowest rib) | kidneys |

| Greater Sciatic Notch (buttocks, beside tailbone) | sciatic nerve |

| Inguinal Triangle (groin) | external iliac artery; femoral artery; great saphenous vein; femoral vein; femoral nerve |

| Popliteal Fossa (back of the knee) | popliteal artery & vein; tibial nerve |

| Hollow under the earlobe | parotid salivary gland, facial nerve |

The endangerment sites are debatable and in some cases definitely misleading. Nerves are everywhere, and there are many locations where they are potentially just as vulnerable to pressure as some of the ones listed above … but no one has ever proposed them as endangerment sites.3 For instance, it’s a bit ridiculous to claim that the sciatic nerve is “exposed” to any degree, because it’s nestled under a lot fat and/or muscle in the sciatic notch deep in the glutes (compared to the ulnar nerve, say, which is indeed quite vulnerable at the elbow).

You can safely massage the scalene muscle group (in the posterior triangle of the neck) without ever bothering a nerve fibre, despite the fact that there are plenty of relatively exposed nerves there (the brachial plexus, a thick web of nerve fibres on the side of the neck).

If you massage any of the endangerment sites, you might feel electrical, zappy, funny-bone-esque pains… but you will probably feel those threatening sensations before there is any actual danger. Healthy nerves aren’t particularly sensitive, but they will speak up if they are on the verge of being crushed or torn — like any other tissue.

Healthy nerves aren’t fragile

Almost no healthy anatomy is particularly “fragile,” with a few obvious exceptions (eyes, testicles). If blood vessels were readily damaged by massage, you’d see that clearly: bruising and blood blisters would be common. But that almost never happens with massage at sensible intensities. And it doesn’t happen to nerves either! If you want to damage any kind of tissue, you’d almost have to make a point of it.

Weirdly, it isn’t actually unheard of to “make a point” of damaging tissue. The goal of provocation therapy is to “break some eggs to make an omelette,” to kickstart tissue healing by damaging it.4 All the various kinds of no-pain-no-gain techniques are of dubious value and have real risks — even serious poisoning, and I wish I was exaggerating.5 For much more information about the risks and benefit of intense massage, see The Pressure Question in Massage Therapy.

But at mild to moderate pressures in mostly healthy patients, there is minimal risk to most nerves, most of the time.

Healthy nerves aren’t particularly sensitive to pressure … but unhealthy ones are

Healthy nerves can mostly be squeezed without producing any symptoms whatsoever. This is an experiment you can do yourself. The ulnar nerve — the “funny bone” — is tolerant of almost any fingertip pressure, and only produces that infamous zing with much greater or sudden force.

However, there are probably circumstances where nerves can be more sensitive — when they have been sensitized by pathology or physical stress (a slow-motion insult like chronic compression). In that situation, nerves can be irritated much more easily, either due to a relatively obvious mechanism like being oxygen starved,678910 subtle systemic inflammation, or more exotic factors like autoimmune disease, or just generally poor fitness (metabolic syndrome, which is in turn a function of diet, fitness, stress, sleep, genetics, and more).

In short, pressure-sensitivity in nerves is probably a symptom. And probably not a rare symptom either. Entirely healthy people are actually a bit unusual, and they are actually rather rare past middle age. In practice, many people may be a little sensitized, more likely to feel all kinds of discomfort — including nerve squishes.

However, being sensitive to pressure isn’t the same thing as being more vulnerable to damage. A moderately sensitized nerve might hurt more when impinged, but probably isn't any more likely to be wounded. (More advanced pathology affecting the health of a nerve might plausibly make it more fragile, but at that point a little nerve pinching is probably the least of your worries.)

The vulnerability of the nerve before it’s pinched is probably more important than the fact that it’s being pinched, or how hard. And how vulnerable the nerves are may be affected by factors that have nothing whatsoever to do with the local anatomy (back, neck, whatever might be hurting), and much more do with systemic health and inflammation.

Nerves and stretch

Nerves may be vulnerable and sensitive to stretch than pressure — especially if they are “snagged” in their sheaths, a predicament known as a tunnel syndromes.11 This might be common. Or not. It’s not entirely clear how much of a problem tunnel syndromes are, but there’s something to them: there are some obvious tunnel syndromes (think “carpal”). But is it the tip of an iceberg of less obvious ones? No one knows!

The problem is not well understood, and neither is the treatment. But neurodynamic stretching is intended to actually free nerves from their snags … or perhaps just stimulate the neural tissue enough to make it a little happier.

What is certain is that nerves can be injured by excessive stretch, and it may even be a more common way for them to get hurt than direct pressure. There might even be a grey zone between “stretch injury” and “tearing nerves free of their snags.” This is all unknown to science. And the rabbit hole goes even deeper…

Micro tunnel syndromes as the mechanism of “trigger points”

Another intriguing possibility is that the common sore spots known as “trigger points” are actually the same thing as sensitive, irritated nerves. Trigger points might be a kind of neuropathy. This is in contrast to the much more widely embraced “tiny cramp” model of a trigger point.12 This idea is highly speculative; I’m including it just because it’s quite interesting in this context.

If so, then pressing on nerves isn’t likely to injure them, or even cause clasically zappy nerve pain: just the familiar aching and burning of common “muscle” pain.

Can neck massage stimulate the vagus nerve? For better or worse?

Vagal stimulation is the least of your worries — or therapeutic opportunities — for massage on the side of the neck and throat. This members-only section of the article explains some genuine dangers of massage in this area, and the much less realistic concern about why people worry about vagus nerve stimulation in the first place — and worry they do! There’s a pseudo-medical legend that vagal massage can actually kill you. I will explain the intriguing carotid sinus reflex, why triggering it with massage is called a “vagal manoeuvre” despite the fact that it’s not very vagal. It’s also not particularly risky or relaxing… and some people really hate it!

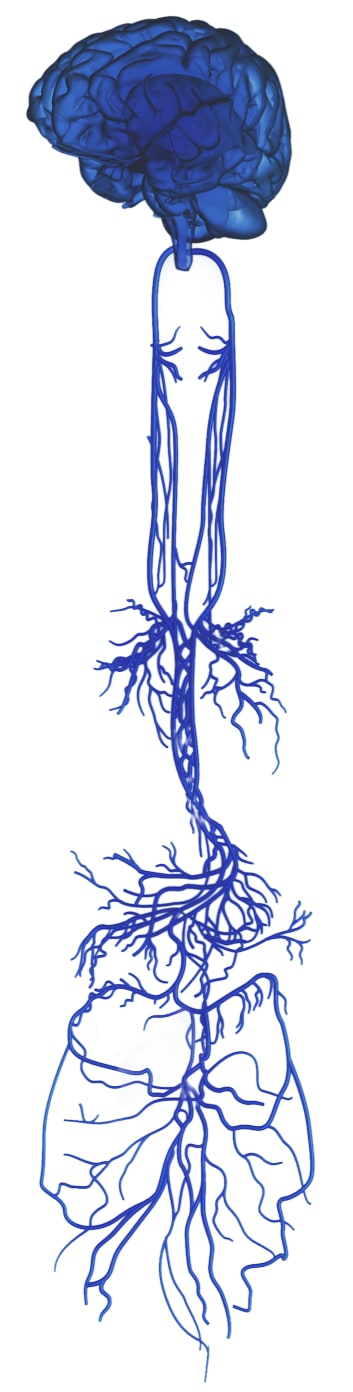

The sprawling vagus nerve

Notice that the many vagal branches almost create a partial map of the viscera, especially the GI tract. Also notice how it’s very clearly a pair of nerves descending from the brain, not “the” (singular) vagus nerve.

This members-only area started out as one of the smaller ones, but has predictably grown with updates to about 2300 words — still not huge, but not exactly small anymore either. There is also an audio version.

Most PainScience.com content is free and always will be.? Membership unlocks extra content like this for USD $5/month, and includes much more:

Almost everything on PainScience.com is free, including most blog posts, hundreds of articles, and large parts of articles that have member-areas. Member areas typically contain content that is interesting but less essential — dorky digressions, and extra detail that any keen reader would enjoy, but which the average visitor can take or leave.

PainScience.com is 100% reader-supported by memberships, book sales, and donations. That’s what keep the lights on and allow me to publish everything else (without ads).

- → access to many members-only sections of articles +

And more coming. This is a new program as of late 2021. I have created twelve large members-only areas so far — about 40,000 words, a small book’s worth. Articles with large chunks of exclusive content are:

- Does Epsom Salt Work?

- Quite a Stretch

- Heat for Pain and Rehab

- Your Back Is Not Out of Alignment

- Trigger Point Doubts

- Does Fascia Matter?

- Anxiety & Chronic Pain

- Does Massage Therapy Work?

- Does Posture Matter?

- A Deep Dive into Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness

- Does Ultrasound or Shockwave Therapy Work?

- A Painful Biological Glitch that Causes Pointless Inflammation

- Guide to Repetitive Strain Injuries

- Chronic, Subtle, Systemic Inflammation

- Vitamins, Minerals & Supplements for Pain & Healing

- Reviews of Pain Professions

- Articles with smaller members sections (more still being added):

- → audio versions of many articles +

There are audio versions of seven classic, big PainSci articles, which are available to both members and e-boxed set customers, or on request for visually impaired visitors, email me. See the Audio page. ❐

I also started recording audio versions of some blog posts for members in early 2022. These are shorter, and will soon greatly outnumber the audio versions of the featured articles.

- → premium subscription to the PainSci Updates newsletter +Sign-up to get the salamander in your inbox, 0–5 posts per week, mostly short, sometimes huge. You can sign-up for free and get most of them; members get more and their own RSS feed. The blog has existed for well over a decade now, and there are over a thousand posts in the library. ❐

Pause, cancel, or switch plans at any time. Payment data handled safely by Stripe.com. More about security & privacy. PainScience.com is a small publisher in Vancouver, Canada, since 2001. 🇨🇦

The salamander’s domain is for people who are serious about this subject matter. If you are serious — mostly professionals, of course, but many keen patients also sign-up — please support this kind of user-friendly, science-centric journalism. For more information, see the membership page. ❐

There is a lot of hype about the vagus nerve and its role in our health, probably because it’s a mighty nerve. The vagus nerve is ginormous, long and complex, and almost entirely dedicated to critical physiology, things like blood pressure, respiration, and digestion. It emerges from the bottom of the brain and passes through the neck and into the trunk, branching out from there to connect to … well, almost everything (most of the organs).

You do not want anything to go wrong with this nerve. True vagal neuropathy exists, and it’s no joke.13 14 15 16 17 But it’s also rare. The medical literature is notably lacking in case studies of injury to the vagus nerve, other than the ones caused by surgery! This is not an easy nerve to injure without a scalpel, and you’re not likely to do it with massage unless you get quite vicious with pressure in an area where that is obviously a Bad Idea. Any massage intense enough to even annoy the vagus nerve would also be risking other kinds of injury, some of them worse:

- ⚠️ Damaging other more delicate nerves (like the brachial plexus).

- ⚠️ Tearing the carotid artery, or causing a clot, or dislodging a clot or some artery gunk (plaque).

- ⚠️ Triggering the carotid sinus reflex strongly, which is mostly harmless but could cause an uncomfortable drop in blood pressure in some people, and fainting in a few.

So the vagus nerve is really the least of your worries in this area.

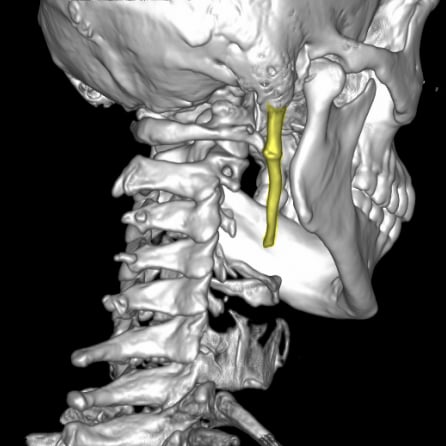

An example of vagus neuropathy due to overgrowth of the weird styloid process (highlighted), which causes mostly neck and throat pain, but can also get weirder. Case courtesy of Dr. Ammar Haouimi, Radiopaedia.org case rID: 81953.

The carotid sinus reflex: vagal or not?

Carotid sinus massage and carotid sinus hypersensitivity trigger the carotid sinus reflex, which is a blood-pressure lowering reflex. Baroreceptors (pressure detectors) are clustered in the carotid sinus, a bulge in the artery where it forks (beside the Adam’s apple). This pesky reflex is probably a major reason why some people are concerned about vagal stimulation from neck massage… and all the more so because it seems to have a hair trigger in some people. Carotid sinus hypersensitivity is actually common, but mostly so mild that people don’t even know they have it. So it’s unusual for it to cause dizzying blood pressure drops or fainting. But it is a thing, and people might be well aware of their tendency to feel weird or gross when this area is rubbed or stretched.

A few people who have this self-awareness probably attribute it to “vagus nerve stimulation” — because the carotid sinus reflex is widely seen as vagal thing. Except… it’s not a vagal thing. Some readers might be quick to try to contradict me on this. “But Paul!” they will say, “Carotid sinus massage is a ‘vagal manoeuvre.’ So it’s obviously vagal stimulation!”

Not so fast.

The “vagal” manoeuvre is not very vagal

The vagal manoeuvre is all about triggering a reflex, exactly the same in spirit as tapping the knee with a rubber hammer to make the knee jerk — except it’s massaging the neck to reduce blood pressure. But this allegedly “vagal” sorcery is not clearly vagal in two main ways:

- The vagal manoeuvre just triggers a reflex… which is not really what people mean by “stimulates the vagus nerve,” any more than you can illuminate a whole office building by turning on the lights in the lobby.20

- That reflex is not technically mediated by the vagus nerve! Surprise! The vagus nerve is all about parasympathetic regulation, but the baroreflex actually works its blood-pressure-reducing magic by dialing back sympathetic stimulation — and the vagus nerve doesn’t do sympathetic.21

If that’s all true, then why is it considered a “vagal” manoeuvre? Because it is so similar in “spirit” to other reflexes that are mediated by the vagus nerve … but cannot be triggered by massage! Two examples:

- There’s the mirror image aortic arch baroreflex. It does the same thing as the carotid baroreflex, but it actually does use the vagus nerve (see last footnote). But I don’t recommend trying to stimulate the aorta with your bare hands. That would get ugly.

- The so-called “vagal” manoeuvre may not have anything to do with the vagus nerve, but it does have something to do with fainting, because it can cause a faint by lowering blood pressure. Which is similar to vasovagal syncope, which is just another kind of reflex syncope (fainting) that actually is mediated by the vagus. Triggering the carotid baroreflex may also be called the vagal manoeuvre because its effect is so similar to “vasovagal syncope,” which refers specifically to fainting (syncope) triggered by seeing blood, stress, and prolonged standing. I’ve been there.22 Vasovagal syncope and the vagal manoeuvre are distinct causes of reflex syncope, and definitely not the same phenomenon … but their kinship is probably why pushing the baroreflex button gets called a “vagal” manoeuvre.23

A glossary of terms related to vagus nerve hype

- Vagus nerve — A mighty nerve that descends from the brain and plugs into … practically all your guts. It regulates visceral function, and is often touted for its potential to relax and restore homeostasis. Vagal therapy hype goes like so: “because your vagus nerve regulates everything, maybe it can fix almost anything if we just tickle it?” Electrical stimulation of the vagus might actually be useful for chronic pain (which is why I’m writing about any of this), but all other “vagus stim” methods are super hand-wavey.

- Syncope — Medical term for “fainting.”

- Reflex syncope — A category of fainting that includes both kind of syncope described below, plus “situational” syncope (fainting from a variety of other triggers, most famously after peeing).

- Vasovagal syncope — The most familiar kind of fainting (e.g. triggered by stress). Vaso for blood, vagal because it’s mediated by the vagus nerve. Not the same as the vagovagal reflex.

- Vagovagal reflex — A complex reflex that mainly kickstarts digestion in response to distension of the gut. Included here in contrast to “vasovagal.”

- Carotid sinus baroflex — A blood-pressure dropping reflex triggered by pressure (baro) in a wide spot (sinus) in the carotid artery, where it forks beside the Adam’s apple. Controlled by the glossopharyngeal nerve, not the vagus!

- Vagal manoeuvre — Triggering the carotid sinus baroreflex with massage. Weirdly, this has nothing to do with the vagus nerve, despite the name (maybe because of conceptual overlap with vasovagal syncope). It can be surprising and unpleasant, but is mistakenly described as “dangerous” by many professionals, maybe to hype the “power” of vagus nerve stimulation — a mistake based on another mistake. Derp!

Clear as mud?

Don’t try to massage the vagus: it won't help, and you might hurt something else

With great power comes great responsibility, and so some people who believe in the power of vagal stimulation are also afraid of the “power” of vagus stimulation. This is unnecessary, because there is no such power to abuse. You cannot “stimulate the vagus nerve” dangerously or significantly with any ordinary massage any more than you can “stimulate” the ulnar nerve to do what the ulnar nerve does, or the sciatic nerve, or any nerve. It’s like trying to turn on a light by massaging the cord (hat tip to reader Mark O. for that excellent analogy).

Therapeutic vagus stimulation with electricity is a real thing, albeit only half-baked. But there is no other known way to meaningfully stimulate the vagus nerve — for good or ill — and certainly not with any neck massage. Not one you’d want to receive, anyway. Or deliver.

There are good reasons to avoid massage of the side of the throat and neck, or to do it only slowly and gently and cautiously. But vagus stimulation is not the reason why.

↑ MEMBERS-ONLY AREA ↑

What happens if you push your luck and push too hard on nerves?

Push hard enough, and you can injure a nerve, of course. In a 2017 incident, a woman’s radial nerve was crushed by an aggressive massage in her upper, inner arm. It’s rare, but it happens.24 Deliberately ramping up pressure on a sensitive nerve is hard to do, like sticking your hand into a jar of scorpions. And yet, surprisingly, sometimes people still do it! It’s amazing what we can put up with if we think it’s necessary, and the no-pain-no-gain attitude inspires a lot of foolishness.

Nerves can recover from a lot of abuse, up to and including being mangled in nasty accidents, or being pinched hard for years. For instance, many people who have severe carpal tunnel syndrome — years of disabling median nerve impingement — often recover just fine once pressure on the nerve is finally relieved by surgery.

In the unlikely event that you cause yourself a nerve injury, it would probably only result in annoying but trivial symptoms that would take a few days to resolve, or perhaps a few weeks at the worst. But I have rarely heard of this happening by self-massage — it’s just too unpleasant as you approach the point of injury to actually get there.

Please beware of tools

I’m sure that there are people, somewhere out there, who have hurt their nerves with self-massage. And I bet most of them were using a massage tool. When you use massage tools, it may be easier to apply too much pressure too quickly … before you have that “I’ve made a huge mistake” moment.

It’s harder to control tools, and hard to tell what’s going on when your sensitive fingers and thumbs aren’t involved. For example: you can easily feel the pulse of an artery when you are massaging with your fingers, but you can’t feel it at all when you use a tool.

So if you use a tool, use it with extra caution.

A nice, simple massage tool … but not recommended for use in vulnerable areas like the sides and front of the throat!

That one time I injured a client’s nerves

Once upon a time I pushed my luck, and injured a patient’s cervical plexus — this area where most people will probably never self-massage strongly. I injured him by applying strong pressures in a vulnerable area too quickly. It was one of my more reckless moments in a decade of mostly quite gentle massage.

He was alarmed and unhappy with me, of course, but his symptoms were minor: he had annoying flashes of moderate pain that slowly faded over about three weeks, and probably the worst thing about it was simply that he was less sure of his prognosis than I was. I knew he’d get better steadily, but he didn’t know if he could trust my opinion! Fair enough.

About Paul Ingraham

I am a science writer in Vancouver, Canada. I was a Registered Massage Therapist for a decade and the assistant editor of ScienceBasedMedicine.org for several years. I’ve had many injuries as a runner and ultimate player, and I’ve been a chronic pain patient myself since 2015. Full bio. See you on Facebook or Twitter., or subscribe:

Related Reading

- The Pressure Question in Massage Therapy — What’s the right amount of pressure to apply to muscles in massage therapy and self-massage?

- The 3 Basic Types of Pain — Nociceptive, neuropathic, and “other” (and then some more)

- Neuropathies Are Overdiagnosed — Our cultural fear of neuropathy, and a story about nerve pain that wasn’t

- Basic Self-Massage Tips for Myofascial Trigger Points — Learn how to massage your own trigger points (muscle knots)

- Massage Therapy Side Effects — What could possibly go wrong with massage? The risks and side effects of massage therapy are usually mild, but “deep tissue” massage can cause trouble

- “Can Massage Cause Muscle and Nerve Damage?” by Ravensara Travillian explores two potential consequences of intense massage, both rhabdomyolysis and peripheral neuropathy.

What’s new in this article?

2023 — Added a glossary for the very confusing terminology related to vagus nerve hype. Recorded a new audio version of the vagus nerve content.

2023 — Added a minor but good (and slightly fun) clarification about the relationship between vasovagal syncope and the carotid baroreflex.

2023 — Just a bunch of miscellaneous editing and polish.

2023 — Substantial improvements to the members-only section about vagal stimulation, and particularly added an audio version of that chapter. (All audio is paywalled, but I’m always happy to grant access to visually impaired readers at no charge.)

2022 — Added a new section: “Can neck massage stimulate the vagus nerve, for better or worse?”

2017 — Added much more information about endangerment sites, discussion of the potential relevance of neuritis, extensive clarifications and editing, and some footnotes.

2008 — Publication.

Notes

- Nerves make people nervous! So to speak. The whole idea of nerves gets people anxious. Could it be a nerve? people ask. Is this a nerve problem? What if it’s a nerve? Is something pinching my nerve? Something must be pinching a nerve.

- Smaller nerves, even when seriously damaged, are unlikely to cause significant pain, suffering, or disability. They recover quicker when damage (just like capillaries heal faster than larger blood vessels). Damage to them is less consequential: they transmit much less information to and from much less tissue, so hurting them just doesn’t have the price tag that we see with larger nerve injuries. And they’re also much harder to hurt in the first place: their itsy-bitsy-ness makes them relatively well insulated physically from pressure. Trying to crush a small nerve is like trying to damage a hair under a quilt rather than a spaghetti noodle under a sheet.

- A good example is the mandibular notch, which is just under the cheekbone and in front of the jaw joint. It’s full of nerves, but very safe to massage — indeed, it’s a particularly nice spot to massage. See Massage Therapy for Bruxism, Jaw Clenching, and TMJ Syndrome.

- The most obvious examples are various kinds of “scraping” massage. Some tools and products, like the notorious Fascia Blaster, also cause bruising (as commonly abuse, which seems inevitable the way that product is marketed).

Although the most obvious effect is bruising from a lot of broken blood vessels, nerves undoubtedly get hurt sometimes as well.

Deep tissue massage sometimes has the same goal (usually unstated), or some soft tissue damage is just accepted as minor collateral damage in pursuit of some other therapeutic goal (such as trying to remove fascial “distortions”, and fascia is much tougher stuff than muscle, vessel, or nerve).

- Sometimes we feel cruddy after a massage, like it was a big workout. Post-massage soreness and malaise (PMSM) is embraced as a minor side effect and hand-waved away by almost everyone as some kind of no-pain-no-gain or “healing crisis” thing. But it needs explaining! Massage is not “detoxifying” in any way (that’s pseudoscientific nonsense). Ironically, it may be the opposite: some PMSM is probably caused by mild rhabdomyolysis, a type of poisoning that can occur even with heavy exercise … and possibly strong massage, which is a plausible hypothesis. If so, it’s a big deal, a nasty side effect. There are also some non-rhabdo explanations for milder PMSM. See Poisoned by Massage: Rather than being DE-toxifying, deep tissue massage may actually cause a toxic situation.

- Wilson CB. Significance of the small lumbar spinal canal: cauda equina compression syndromes due to spondylosis 3: Intermittent claudication. J Neurosurg. 1969;31:499–506. PubMed 5351760 ❐

An old topic review that explains that the belief that the pain may be caused by impairment of circulation to the capillaries of the spinal nerve roots.

- Mackinnon SE. Pathophysiology of nerve compression. Hand Clin. 2002 May;18(2):231–41. PubMed 1237102 ❐

From the abstract: “Both ischemic and mechanical factors are involved in the development of compression neuropathy.” In other words, mechanical factors only — just being pinched — probably does not cause nerve pain.

- Kobayashi S, Shizu N, Suzuki Y. Changes in nerve root motion and intraradicular blood flow during an intraoperative straight-leg-raising test. Spine. 2003 Jul 1;28(13):1427–34. PubMed 12838102 ❐

Kobay et al. surgically examined blood flow to a lumbar nerve root while the leg was in a painful position. (They peeked into twelve backs with a history of symptomatic disk herniations and nerve pain.) They found that “the intraoperative reverse straight leg raise test showed that the hernia compressed the nerve roots, and that there was marked disturbance of gliding, which was reduced to only a few millimeters,” and “during the test, intraradicular blood flow showed a sharp decrease [40 to 98%] at the angle that produced sciatica.”

Intriguing. It’s probably the physical distortion of the nerve root that caused the loss of circulation, and the combination of the two that was painful. Successful treatment seemed to back this up: “After removal of the hernia, all the patients showed smooth gliding of the nerve roots during the second intraoperative test, and there was no marked decrease in intraradicular blood flow.”

- Jayson MI. The role of vascular damage and fibrosis in the pathogenesis of nerve root damage. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992 Jun;(279):40–8. PubMed 1534723 ❐ It “appears likely that venous obstruction with resultant hypoxia is an important mechanism leading to nerve root damage.” And why would blood supply to a nerve root be impinged? According to Jayson, “Vascular damage and fibrosis are common within the vertebral canal and intervertebral foramen.” Especially after surgery! But not only after surgery. The delicate capillaries around nerve roots seem to degenerate just like joints get arthritic, and that process is probably accelerated by biological factors like autoimmune disease, cardiovascular disease, and chronic low grade inflammation … which are in turn affected by diet, fitness, stress, sleep, etc.

- Sore spots in muscles are measurably hypoxic. See Toxic Muscle Knots

- Sometimes, due to pathological processes and physical predicaments, nerves get pressed against and stuck to the walls of their tubes, like microscopic velcro. This predicament is usually called “neural tension” or a “tunnel syndrome.” You don’t want this happening to your nerves any more than your cat wants tape on its paws. It affects their function. The membrane of the nerve itself is no longer floating freely, so ions can no longer rush in and out of that section of membrane quite so well. The result: pain, numbness, tingling. Neuropathy.

- Quintner JL, Bove GM, Cohen ML. A critical evaluation of the trigger point phenomenon. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015 Mar;54(3):392–9. PubMed 25477053 ❐

This infamous paper firmly concludes that the integrated hypothesis of trigger point formation is “flawed both in reasoning and in science,” and they propose some replacements, including inflamed nerves — small nerves chronically slightly irritated by minor tunnel syndromes.

For more about the controversy over the nature of trigger points, see Trigger Points on Trial.

- Badhey A, Jategaonkar A, Anglin Kovacs AJ, et al. Eagle syndrome: A comprehensive review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2017 Aug;159:34–38. PubMed 28527976 ❐

- Klein TAL, Ridley MB. An old flame reignites: vagal neuropathy secondary to neurosyphilis. J Voice. 2014 Mar;28(2):255–7. PubMed 24315656 ❐

- Rees CJ, Henderson AH, Belafsky PC. Postviral vagal neuropathy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2009 Apr;118(4):247–52. PubMed 19462843 ❐

- An Y, Park K, Lee S. The First Case Report of Bilateral Vagal Neuropathy Presenting With Dysphonia Following COVID-19 Infection. Ear Nose Throat J. 2022 Feb:1455613221075222. PubMed 35164601 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 51343 ❐

- Tan ET, Johnson RH, Lambie DG, Whiteside EA. Alcoholic vagal neuropathy: recovery following prolonged abstinence. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1984 Dec;47(12):1335–7. PubMed 6512554 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 51339 ❐

A reader commented on this issue with a superb example of ridiculous fear mongering about carotid sinus sensitivity:

“Back in the '70s my university had a required Health course for incoming students. I remember to this day the instructor’s dire warnings that we were NEVER to attempt to take a carotid pulse on both sides of the neck simultaneously. Fainting or sudden death would surely be the result. She also told us of the time she had to rush from the podium to save a student who foolishly attempted the maneuver on himself.”

Such drama! “Save”? From, at worst … fainting. And what exactly was she going to do anyway?

- Lacerda GdC, Lorenzo ARd, Tura BR, et al. Long-Term Mortality in Cardioinhibitory Carotid Sinus Hypersensitivity Patient Cohort. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2020 02;114(2):245–253. PubMed 32215492 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 51342 ❐

- A reflex arc is precise: it does only one thing, and it’s pathway is just one “lane” of the huge multi-lane highways of nerves. The vagus nerve is particularly large, and mediates several reflexes and much else. When people talk about “vagal stimulation,” they are not talking about triggering a single reflex: they are (very optimistically) talking about stimulating all of its functions … which would induce deep relaxation. Triggering your baroreflex doesn’t do that.

- “The” baroreflex has two batches of pressure sensitive nerve endings, one in the aortic arch in the chest, and the other in the carotid artery in the neck. But the baroreceptors in the carotid sinus are wired to the CNS by the glossopharyngeal nerve, not the vagus. The aortic arch baroreceptor axons travel within the vagus nerve, but that’s not what the vagal manoeuvre stimulates!

Weirdly, the vagal manoeuvre is actually kind of the opposite of vagal stimulation. Blood pressure can be reduced either by decreasing sympathetic stimulation, or increasing parasympathetic. These two divisions of the autonomic nervous system are very yin and yang. Blood pressure can be boosted by sympathetic or tamed by parasympathetic … but you can also just remove the boosting, and that is in fact how the baroreflex works. It slows the flow of the signals that raise blood pressure, rather than squirting out more of the signals that lower it!

The aortic arch part of the baroreflex does exactly the opposite, and does use the vagus to lower blood pressure with parasympathetic nerve impulses. Mirror image functionality! It’s quite interesting that we have redundant reflexes that tackle the same problem using opposite approaches.

It’s all fiendishly complex, and I am not going to definitively say that the vagus nerve is completely uninvolved in the carotid sinus baroreflex. For instance, there is evidence that the vagus nerve does contain sympathetic fibres, and so there may be vagus involvement in the sensory half of the carotid baroreflex arc. But it’s clearly mostly a sympathetic result.

Like I said above, the devil is in the details… and there are a lot of details here. It took me a long time to write and fact-check this explanation.

I’ve only fainted once in my life, and it was classic vasovagal syncope: I was on Mayne Island, one of the beautiful Gulf Islands of British Columbia, Canada. I had been out hunting oysters in the sun. When I got back to the farm where I was working at the time, I tried to shuck my first oyster with a screwdriver… and it slipped and plowed into my palm. Oops! Out like a light! I felt like a robot shutting down, and then verrrrry slowly rebooting. I still remember the view of the kitchen floor as I tried to remember who I was. Good times!

- That’s just a guess. Researching the etymology of “vagal manoeuvre” would take more time than the topic deserves here.

- Hsu PC, Chiu JW, Chou CL, Wang JC. Acute Radial Neuropathy at the Spiral Groove Following Massage: A Case Presentation. PM R. 2017 Apr. PubMed 28400223 ❐