Tennis Elbow Guide

Not just for tennis players! A detailed, science-based tour of the nature of the beast and reviews of all the treatment options

“Tennis elbow” is one of the classic repetitive strain injuries (RSI): a combination of chronic exhaustion and irritation in the muscles and tendons on the back of the arm and the outside of the elbow, which lift the wrist and fingers (extension). Hotter, sharper pain right at the elbow often indicates a classic case dominated by tendon trouble. Duller, more aching pain, spread more evenly around the back of the arm, may suggest that muscle pain is dominant — a diagnostic possibility that may be underestimated (my own pet theory), and such cases may be much more treatable.

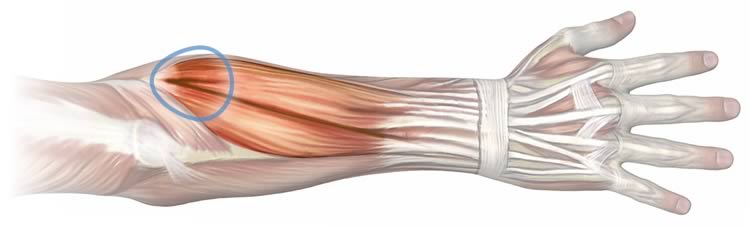

The muscles of the back of the forearm gather into a single tendon. In tennis elbow, both the tendon and the muscles themselves may be the source of pain.

This is a detailed guide to tennis elbow. It’s at least 10 times longer than the articles on the topic that dominate Google search results (if not much more so at about 15,000 words, 70 minutes reading time). It’s readable enough for patients, but heavily referenced and rigorous enough for pros and experts.

Eight weird things about tennis elbow

There are (at least) eight odd things about tennis elbow, all of which will be explored below:

- Although common, it’s barely studied and poorly understood. This is standard for most musculoskeletal problems, but it still feels weird to me.

- Too much tennis is still a good way to get it, but it’s really much more about elbow strain in the workplace these days — but no one actually knows if that includes typing and mousing.

- It has less to do with elbow strain than anyone thinks, and more to do with systemic vulnerability.

- Even if it is a proper tendinitis, it’s not a tendinitis of just one tendon, but a whole cluster of them — unique among common types of tendinopathy.

- Despite all those tendons, or even because of it, it may also be an unusually muscle-y tendinitis, with muscle pain making much more of a contribution than most other tendinopathy.

- It’s not really “inflamed,” per se — at least not the way we usually think of it.

- Tennis elbow can almost certainly be a symptom or complication of neck problems — which is a major curve bull that can seriously affected diagnosis and treatment.

- Psychological factors actually matter, especially in chronic cases.

This is a surprisingly strange and understudied condition. “Is there any science out there?” Boyer et al. asked in 1999. “Numerous nonoperative modalities have been described for the treatment of lateral tennis elbow. Most are lacking in sound scientific rationale.”1 Unfortunately, not much has changed.

When a lot of remedies are suggested for a disease, that means it can’t be cured.

Anton Chekhov, The Cherry Orchard

The science of conditions like this is generally much more of a mess than you might think.2 Although the situation is improving, it is still a surprisingly difficult, mysterious, and interesting condition — involving more mind and muscle than anyone suspects.

Computer elbow? “Tennis” elbow is not just caused by tennis

Tennis elbow is a misnomer — this is primarily a workplace injury. Although whacking a tennis ball is one great way to get a sore elbow, anyone who does hard and/or highly repetitive work with their hands is two to three times more likely to develop lateral epicondylitis than people who don’t.3 That’s a lot of risk for a lot of workers. For contrast, Achilles tendinitis is almost exclusively a sports injury, but isn’t named for it; tennis elbow, which is barely a sports injury, is nevertheless named for it!

Really, any source of strain will do. Reader John S. tells me he has “a minor case caused by screwing caps on beer bottles!” Home brew hazard!

“Golfer’s elbow” is a mirror image of tennis elbow: same thing on the inside of the elbow instead of the outside, affecting the muscles and tendons that flex the wrist/fingers instead of extending them. The conditions are extremely similar despite living on different sides of the elbow; anything I say about tennis elbow probably applies to golfer’s elbow, unless I mention otherwise.

Does computer use cause tennis elbow?

Is computing “strenuous”? Mousing and keyboarding might be a common way to overuse an elbow — but it’s surprisingly unclear.45 I do suspect that “computer elbow” is a thing, just not a proven thing.6 If I’m right, it’s likely a large source of lateral epicondylitis, because so many people use computers so much.

Although using a computer obviously isn’t especially intense, it is highly repetitive, and ridiculously common. Hardcore computer users outnumber serious tennis players — and carpenters and meat packers and so on — at least a thousand to one. (In wealthy nations anyway.7) The weird part is just that no one’s ever actually confirmed it with good hard data.

Lateral epicondylitis versus lateral epicondylalgia

Tennis elbow is usually called lateral epicondylitis, a type of tendinitis, because that is what it seemed to be. It’s not so much a tendon that’s affected, but a whole group of them, a super-tendon: the common extensor tendon of the forearm. A group of wrist and finger tendons on the back of the forearm that converge on the bump on the outside of the elbow (lateral epicondyle).

Many common musculoskeletal conditions have names that are based on what we think is actually going on, but it’s amazing how often it turns out to be wrong.9 But the tendinitis implication isn’t safe, in two ways:

- It may not be a tendinitis, but it’s not clear always that it’s actually the tendon that’s in trouble. It might be, and it probably is in many cases, but the complex group of muscles the tendon is attached to also seems to get extremely sore, and may even be the main problem. In several ways, many cases do not behave like classic tendinitis, and so it may be safer to just think of it as lateral elbow pain (lateral epicondylalgia).

- It may not actually be inflamed, not as we usually think of it (see next section), in which case the term tendinopathy is probably more apt than tendinitis.

Tennis elbow is not a tendinitis exactly

The word tendinitis means “tendon inflammation,” but it turns out there isn’t actually much obvious inflammation in overused tendons — at least, not beyond the early stages10 — and so the name tendinitis might not be such a great fit. Anti-inflamatory treatments are the popular first-line of defense against alleged tendinitises, which would make a lot more sense if the tendon were really inflamed. But it isn’t — not really — and so the most popular and accessible treatment has a problem.

We should probably think of it as a “tendinopathy” which is Latin for “something wrong with a tendon.” Tendinopathy is a deliberately vague term, reflecting our ignorance, because — and I know this is going to shock you — experts really don’t know what’s going on. Tendinopathy refers to “any painful condition occurring in and around tendons in response to overuse,” but “recent basic science research suggests little or no inflammation is present in these conditions.”11 Or, in any case, not “classic” acute inflammation (like we see with an infection or wound: red, hot, swollen). Classic, acute inflammation is only present in the early, acute stages of tendinitis.

There is “inflammation,” though! It’s just so subtle and different from what we’re used to thinking of as inflammation that it almost needs a different word.12 It’s like the difference between a fire and coals — coals that aren’t even hot enough to glow, or so dimly that you can only see them in the dark.

A more distinctive and consistent feature of tendon RSI is connective tissue degeneration.1314).

That all said, I still think tendinitis remains a fair and useful term in a you-know-what-I-mean way. I don’t think we need to change the term just to reflect the fact that there’s no inflammatory bonfire raging in chronic tennis elbow.

Inflammatory treatment implications

All of this goes a long way to explaining why your standard regimen of icing and ibuprofen doesn’t exactly work miracles with tennis elbow, or any other tendinopathy. Anti-inflammatory drugs may be useful as minor symptom control methods, but they are mainly effective with acute inflammation and are probably just a biochemical mismatch with whatever’s going on in a tendinitis.15 Ice is also good at quenching acute inflammation, temporarily, but probably can’t put out a “fire” that isn’t present in tendinopathy. (But it might have some potential as a tissue stimulant, as opposed to fire-extinguisher — more on this below.)

X-factors: other things that probably boost vulnerability to tennis elbow

It’s not all just about physical loading. It’s about how our biology copes with it. It’s easy to assume that overuse injuries like tennis elbow are mainly caused by physical strain, but the reality is undoubtedly messier.

As with all other kinds of “simple” musculoskeletal problems and injuries, not everyone is equally vulnerable to them. Exactly the same loading can be just fine for one person and a disaster for the next. So what are the differences?

Many factors affect our vulnerability to load.16 There are factors you cannot control, like genetics and pathology. For instance, simply having any other kind of pain is one of the clearest risk factors for a having a rough ride with tennis elbow.17

And there are factors that you can control, like smoking and fitness (not that it’s easy). Smokers are at least twice as likely to get tennis elbow, for instance18 — and there’s a citation like that for every condition I have ever written about. As you may have heard, smoking is bad for you, but it’s far more relevant to body pain than most people know.

A stranger example: tennis elbow may be a complication of a neck problem. Rates of tennis elbow are actually higher in people with irritated nerve roots in their necks (“radiculopathy”).1920 Tennis elbow could be the only symptom, or there could be other signs of cervical radiculopathy (neck pain, shoulder pain, other arm pain, tingling, weakness).

And then there are the factors you might be able to control, but only with great difficulty at best: the very awkward psychological and personality factors.21 These do not imply that any case of lateral epicondylalgia is “all in your head,” but there is little doubt that what’s in your head is influential. Dread and anxiety about the effect of your pain on your career, for instance, could easily drive the phenomenon of “sensitization” — basically making the same problem hurt more, because your brain is taking the problem more seriously, treating it like more of a threat. In the weird world of pain, “threat perception” and “pain” are woven together like the snakes of the caduceus.22

Diagnosis of tennis elbow

Most elbow pain without any other obvious explanation is either tennis elbow or golfer’s elbow, especially if you’ve been working at the computer a lot (or playing a lot of tennis or golf). Tissues right around and below the bony projection on the side of your elbow will be tender. The muscles on the back of the arm, if you dig into them a bit, will also be tender — in fact, you may be amazed at how sore they are.

Long days at the keyboard will generally make it worse, but those stresses are happening in slow motion and it may not be obvious that typing and mousing are a problem. Whacking a ball with a racquet, on the other hand, yanks hard on the extensor muscles and their tendons — and that always hurts, if you have tennis elbow. Computer users can almost immediately confirm a tennis elbow diagnosis just by trying to hit a ball around a few times. Give it a try! Or swing a golf club, to test for golfer’s elbow — of course. (I didn’t really need to spell that out, did I?) It may be a little inconvenient to find an opportunity to test your elbow this way, but it’s a really reliable method.

If tennis does not irritate your elbow pain, it’s definitely not tennis elbow.

There’s a more convenient test (although somewhat less reliable). The classic simple test for any tendinitis is to simply pull firmly on the tendon. In the case of tennis elbow, this means resisted extension from flexion. Flex your wrist, hold it in place with your other hand, and then try to straighten it. (Do the same test with the wrist bent the other way to test for Golfer’s elbow.)

Don’t forget the evidence that tennis elbow may be a symptom or complication of neck trouble!23

What’s the worst-case scenario for tennis elbow?

The worst cases cause severe pain and significant functional disability for years at a time. Fortunately, such extremes are rare, because they can become existential crises for a careers that depend on keyboarding. Many chronic injuries and pain problems can threaten careers to some degree, but this is an obnoxiously direct attack on your livelihood. People can and do change their lives to work around lateral epicondylalgia. Like carpal tunnel syndrome, some people simply give up trying to make a living with a keyboard and mouse. But there is hope, and most of those people probably shouldn’t quit their jobs — there are treatment options that, while hardly guaranteed to work, are worthwhile and often neglected.

If you’re really serious about your racquet sports or golf, that’s also a major issue.

Even at its worst, the pain is usually not extreme by the standards of some kinds of notoriously severe body pain.24 Although the pain severity rarely escalates to the level of general disability — e.g. keeping you awake at night, interfering with activities that have nothing to do with using that arm — its interference with work can change lives by forcing career changes, and that is serious indeed.

For most people, the condition is usually just an annoyance for a while. It’s the minority of stubborn cases that make the condition notorious.

Tennis elbow recovery time

How long will it take? The short answer is that a typical case of tennis elbow will take about three months to get clear of. Six months is considered unusually stubborn. (These numbers are roughly appropriate for all kinds of tendinitis.)

There is no longer answer. There is simply no good data on this topic. Injuries that affect a lot of athletes get some research attention on “return to play” times — e.g. muscle strains, Achilles tendinitis. But not tennis elbow.

The popular perception is that tendons don’t heal well, like cartilage or fingernails. One expert source claims “the less blood delivered, the longer it takes for tissue to heal,” but there’s much more involved in this equation, and the truth is in the middle: tendon definitely can heal, but it’s not exactly quick about it (like the mouth, say, the fast healing champ of the human body). And there are poorly understood vulnerabilities and complications that can slow down recovery and increase the risk of re-injury.25

Introduction to tennis elbow treatment

There are plenty of non-surgical treatments out there for tennis elbow (lateral epicondylitis) — all of them are reported as having good results, yet none of them is any better than placebo.

Dr. Skeptic, Tennis elbow treatment: perception versus reality

Tennis elbow may respond well to some simple and inexpensive treatment methods. On the other hand, it’s not clear that any of them is anything more than a placebo.

Some important general treatment principles to bear in mind

- Cynicism about treatment options is fully justified. The marketplace is cluttered with decades of treatment ideas and gimmicks that have much more to do with marketing and hype than good science or medicine. We have to prioritize the imperfect options by focusing on what is most plausible, safest, and cheapest. See Quackery Red Flags.

- Everyone really is different, chronic pain is multifactorial by nature, and so no one treatment is ever likely to be the solution for any one person. This is why there will probably never be one well-known treatment that works for most cases of tennis elbow.

- General biological vulnerability (poor health/fitness) may be more important than any specific cause of tennis elbow. See Vulnerability to Chronic Pain.

- The “secret” to all rehab is “load mangement”: first calm it down, then build it up. That is, we can heal from practically anything if we take it easy and then take baby steps back to normal function. This is especially true for RSIs like tennis elbow.

- Symptom relief gets a bad rap as mere “masking” of symptoms, but beggars can’t be choosers, it’s usually the best we can do, and it’s not useless. Any source of effective symptom relief is generally useful for creating windows of (rehab) opportunity, which can be a great help with load management. See Masking Pain is Under-Rated.

- A major factor in the stubborness of most chronic pain is sensitization. Many treatment efforts that might otherwise succeed will fail if sensitization is raging out of control. But there’s nothing about sensitization that is specific to tennis elbow.

- The “power” of the placebo effect is badly overhyped: it is not a magical mind-over-pain superpower and its effects tend to be minor and/or brief. Beware of embracing placebo. See Placebo Power Hype.

Medications for tennis elbow

Medications for tennis elbow are mainly about providing a little pain relief. They aren’t going to actually improve the condition. Worse still, they might actually impair tendon recovery.26 That effect has never been confirmed, but it’s possible, and an excellent reason not to overdo it with pain meds.

“Masking symptoms” is often maligned, but sometimes symptoms need masking! For instance, when you need a little pain relief during activity you cannot avoid. And many of us have activities we cannot avoid, like childcare, or a career that naturally involves some forearm tendon loading (like mine, for instance, which involves effectively infinite typing).

Over-the-counter (OTC) pain medications are fairly safe and may be somewhat effective in moderation, and work in different ways, so do experiment cautiously.

However, they are probably effective during the acute phase of tennis elbow only. Chronic cases are probably not inflamed enough, or in the right way, to be affected by the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), such as aspirin (Bayer, Bufferin), ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), and naproxen (Aleve, Naprosyn).27

Acetaminophen/paracetamol (Tylenol, Panadol) are not “anti-inflammatories,” and may take the edge off the pain in some people.

Don’t take any pain-killer chronically — risks go up over time, and they can be serious. Acetaminophen is one of the safest of all drugs at recommended dosages but overdose can badly hurt livers.28 The NSAIDs all reduce inflammation as well as pain and fever, but at any dose they can cause heart attacks and strokes29 and they are “gut burners” (they irritate the GI tract, even taken with food).

Voltaren is an ointment NSAID, effective for superficial pain and therefore much safer,30 because the systemic dosage is much smaller. This is by far the best choice for pain control during acute flare-ups. There are other topical analgesics with potential, but Voltaren has many advantages. Nevertheless, I do recommend experimenting with the widely available salicylate creams (an ingredient in many “muscle rub” products), as well as the “spicy” muscle rubs (Tiger Balm and friends, the rubefacients). I do not recommend arnica creams (homeopathic/diluted or full-strength herbal). See my guide to topical analgesics for more information about all of these.

For a much more detailed discussion of medications for tendinitis, see the general repetitive strain injuries tutorial. For more general information about all kinds of pain-killers, see The Science of Pain-Killers.

Steroid injections: certain risks and uncertain rewards

Corticosteroids are potent anti-inflammatory agents. Injection is greatly preferred for its precision and avoidance of systemic effects,31 and it’s a popular option for all tendinitises. This is just an overview; for more detailed information about the pros and cons of steroid injections, see the Guide to Repetitive Strain Injuries.

Corticosteroid injections often produce substantial but temporary pain relief, at the cost of a (minimally) invasive procedure with some risks. The evidence is mixed and complicated for all musculoskeletal conditions, and clearly better than some.

For instance, data supporting short-term benefit is particularly decent in the case of tennis elbow3233 — hooray! You may have noticed that there’s not a lot of actually positive evidence cited in this review. It’s a rare pleasure when it crops up. But the caveats are substantial, of course…

There is also evidence that the long-term results for steroids are much less rosy, or even nasty.34 What could possibly go wrong? Well, steroids actually eat connective tissue. Slowly. It’s not like strong acid! But it’s a Very Bad Thing, and probably explains the data about long term harm.35

And there is specific evidence of long term harm for tennis elbow. When Bisset et al. (cited earlier), compared steroids to physiotherapy, steroids performed quite a bit better for the first several weeks, but then they actually regressed after that: “the significant short term benefits of corticosteroid injection are paradoxically reversed after six weeks.” Ruh roh!

Even the short term benefits have caveats. As good as they are, you have to wait a few days for your short term benefits and risk regression when they fade several weeks later. An interesting 2005 study focused on the very short term effects of steroids for tennis elbow, and they found that it briefly gets worse before it gets better: about a day or two of increased pain before you get the payoff.36 So it’s not like you just immediately feel better, which is certainly worth knowing.

Since the nature of repetitive strain injury is that tissue slowly “rots” and degenerates under stress, steroid corrosion of connective tissue is an ironic hazard — steroids may dangerously exacerbate the basic problem even as they relieve pain. This is why physicians wisely limit steroid injections to about three. With minimal dosing, the risk is also lower, and the prospect of significantly greater pain relief for even a few weeks might be worth the risk.

- Worst-case: no benefit, direct worsening of the problem (accelerated degeneration of connective tissue), and a poorer long term result.

- Best-case: significant short term pain relief without any significant adverse effects, and a useful aid in rehab.

But the best outcomes are probably rare. A 2016 trial showed that general physiotherapy offers clearly better bang-for-buck compared to steroid injections: “Physiotherapy, not corticosteroid injection, should be considered as a first-line intervention for lateral epicondylalgia.”37

Exercise therapy for tennis elbow

Although resting is initially critical, a careful balance of rest and a variety of exercise is the basic formula for recovery from most RSIs over time. Nothing in biology seems to recover without a little stimulation — and nothing sabotages recovery like too much stimulation.

You should gradually and progressively train the muscles and tendons to tolerate exercise again. Chances are good that you will need to go more slowly than you think; these conditions rarely change quickly. Mobilizations and stretching (next topic) are good examples of easy, intermediate exercises — ways to start exercising without over-stimulating.

At all stages, though, you start with small doses, and the need to give plenty of rest (recovery time) is crucial throughout. It’s never just exercise, and never just rest, but a long term balancing act between them. Stretching and mobilizing may be a terrific way to stimulate without overloading in the early stages (see next section). Much more on strengthening specifically later in the guide: the evidence for it, exactly how to do it, and all about the eccentrics/isometrics hype.

Stretching for tennis elbow (and “mobilizing”)

Although stretching is highly over-rated as a general tonic,38 it may be useful for a more specific goal like this. Muscle trigger points (muscle knots) might respond well to stretch — hardly guaranteed, but in my experience it’s a bit more likely to work out with this muscle group. Since trigger points are usually a factor in tennis elbow, I always recommend at least trying some stretch.

It is tricky to fully stretch the muscles involved in tennis elbow, but you can do it like this: while standing, with your arm in front of you, place the back of your hand against a wall with the fingers pointed out to the side, straighten your elbow, and then press into the wall so that your wrist is flexed sharply. Hold for a minute. Be cautious: do not stretch too hard, and release the stretch gradually, over several seconds at least.

I also recommend mobilizing (see Mobilize!), which is basically just rhythmically stretching the wrists one way and then the other: more stimulating and neurologically interesting than simple static stretching alone. To mobilize your forearms:

- Sit on the edge of a bench, table, or firm bed — somewhere you have room to put your hands down on a firm surface on either side.

- Place your hands palm down, fingers pointed backwards. This sharply extends your wrists, stretching the inside of your forearms (the flexor muscles). Once you are in this position, you can lean into it a little to increase the intensity, to taste.

- Now a new position: bend your wrists the other way. Place the backs of your hands down (fingers still backwards). This sharply flexes your wrist, stretching the backs of your forearms (extensor muscle group). Again, you can lean into it as much (or as little) as you like.

- So those are the two positions, stretching the wrist each way. Now, once you’ve got both of those stretches down, it’s easy to alternate sides…

- Lean into the stretch on the left while switching the wrist position on the right.

- Then lean into the right while switching the wrist position on the right.

- Repeat!

Icing for tennis elbow

Tendinitis supposedly hurts because of the “inflammation,” but as explained above inflammation is actually limited or missing entirely in chronic cases. In acute (fresh) cases, or serious flare-ups of a chronic condition, ice might actually control inflammation and potentially retard progression of the condition — a genuine biological benefit, as opposed to just a bit of pain control — but unfortunately no one knows if it actually works.

As a treatment for chronic cases, ice has a different and potentially more valuable role: it’s a way of strongly stimulating tissue without stressing it. This may help healing, and will do no harm — as long as you are careful to avoid “burning” your skin (frostbite). Never apply ice directly for more than a minute or two at a time. Icing many times per day may be therapeutic. This treatment is not based on any evidence, however39 — it’s just a reasonable theory. For (much) more information, see Icing for Injuries, Tendinitis, and Inflammation.

Cases dominated by muscle pain will usually not respond to icing, and may even be aggravated by it — although that risk is probably quite low.

Ice and heat: contrast hydrotherapy

“Contrasting” is the alternating application of heat and cold to the area. This boosts circulation to the entire arm and hand without having to exercise it (potentially stressing tissues that are already over-stressed). Like icing, this is stressless tissue stimulation, but with a much greater impact on circulation in particular. Like icing, there’s no direct evidence that this actually works, but it’s a solid theory — and, done right, it is actually extremely pleasant! Obviously, please don’t burn yourself with too-hot water. By far the most convenient method of doing this is in a double-sink: one filled with cold water, the other with hot water. For more information about contrasting, see Contrast Hydrotherapy.

Massage for tennis elbow

There is exactly one scientific trial of massage for tennis elbow that I am aware of, and it delivers evidence of substantial benefit40 — although it’s a bit too good to be true. The main justification to attempt massage is not any scientific proof of efficacy, which is a high bar, but just that it’s biological plausible that it would be helpful, safe to experiment with, and even cheap: your forearm is a particularly easy body part to reach for self-massage and massage with various accessible tools.

Mainly use firm, long, lubricated strokes from hand to elbow on the back of the arm. Be firm but please do not be rough — take it easy, especially at first.

To get more specific, see Massage Therapy for Tennis Elbow and Wrist Pain, which explains exactly where the worst trigger points (sore spots) usually form in the arm muscles.

Some experts believe that a muscle in the neck, the anterior scalene muscle, has a surprisingly strong relationship with trigger points in your forearm muscles.41 Self-massage of this muscle is not particularly easy, and not as safe as arm massage, but probably worth learning and experimenting with cautiously in tough cases: see Massage Therapy for Neck Pain, Chest Pain, Arm Pain, and Upper Back Pain for more information.

For more guidance on self-massage technique, see Basic Self-Massage Tips for Myofascial Trigger Points. For extremely detailed guidance on treating muscle pain, see my book: The Complete Guide to Trigger Points & Myofascial Pain.

Friction massage

Like all tendinitises, tennis elbow may respond well to a very specific massage technique called “friction massage.” The evidence so far is discouraging, but also still inconclusive,42 and — just like more traditional massage — it’s safe and cheap enough to be worth experimenting with.

Rub back and forth over the tendon (across it) gently with your thumb or finger pads until the sensitivity fades, which should take no more than a minute or two, and then increase the intensity slightly and repeat. If the intensity doesn’t ease, discontinue. For more information, see Deep Friction Massage Therapy for Tendinitis.

Ergonomics for tennis elbow

In general, the significance of individual ergonomic factors is drowned out by the sheer volume of time spent working. However, the only thing worse than having to work too much is having to do it inefficiently or awkwardly, so it’s always worth improving whatever you can improve. If you use a computer heavily, you may wish to invest in some upgrades to your computer workstation to aid in healing from “computer elbow.”

Keyboards are straightforward, as there is really only one important thing to know: don’t lift the back of your keyboard. This is a bizarre anachronism that exists only because early keyboard manufacturers wanted computer keyboards to seem more like typewriter keyboards (steeply angled). However, the ergonomic problem with this is susbtantial. An elevated keyboard forces you to keep the wrists “cocked” into extension, holding all of the extensor muscles of the forearm in contraction, which may aggravate computer elbow situations significantly — avoid, or mitigate it with a gel wrist pad (to lift the heel of the hand).

The type of mouse you use is a relatively minor factor in repetitive strain injuries.43 However, I certainly recommend choosing a mouse you like — one that seems comfortable to you, and does not annoy you with any design quirks. Wirelessness is a particularly good, basic feature for almost everyone.44 (And practically the default nowadays. Not so when I first wrote about this in the early 2000s.)

For the same reason, I recommend basically the best quality mouse.

Mouse shape and button design are pretty trivial factors. Basically, comfort is all you’re looking for, and people’s hand shapes and usage patterns are so different that one woman’s “ergonomic” mouse is another’s hand torture device.

Surgery for tennis elbow

If you went looking, you’d have no problem finding studies that make surgery for tennis elbow sound like a great deal. You don’t even have to go looking, because I’ll share a couple examples: in a classic 1961 article, the late, great British surgeon RS Garden reported that “no patient failed to benefit in some way from the operation.”45 Decades later, a modern paper reports 78 of 80 surgery patients had “improved clinical outcome at both short- and medium-term follow-ups with few complications.”46

But these studies, both old and new, did not compare surgery to a placebo — a common problem with surgical research.47 They are also studying a conventional surgical approach that doesn’t exactly scream “plausible.” The conventional way to treat tennis elbow with surgery is to remove the part of the tendon that hurts. Often euphemistically called a “release.” It sounds rather ham-handed to me.

There’s only one study comparing real surgery to a fake surgery, by Drs. Kroslak and Murrell.48 The results were completely disappointing — hardly what you’d expect if surgery was really effective.

Eleven patients were treated with the Nirschl technique (surgical excision of the macroscopically degenerated portion of the extensor carpi radialis brevis tendon), and 11 received a sham operation: a skin incision, exposing the tendon. Both groups improved equally: “The only difference observed between the groups was that patients who underwent the Nirschl procedure for tennis elbow had significantly more pain with activity at 2 weeks.” Kroslak scathingly concludes:

There is no benefit to be gained from the gold standard tennis elbow surgery over placebo surgery in the management of chronic lateral epicondylitis. In fact, the Nirschl procedure may increase the morbidity of the condition in the immediate post-operative period.

If everyone generally got better, isn’t that a good thing? Quite the opposite: it means the benefit was pure placebo, and it didn’t matter what kind of surgery was done as long as the patient believed they were getting a powerful treatment.

Food for thought, isn’t it?

Surgery lite: denervation

The main surgical alternative to consider is denervation: destroy or damage the sensory nerve supply for the tendon, rather than removing part of the tendon itself. They are usually destroyed with heat: “kill it with fire!” Specifically, this is known as electrocoagulation or radiofrequency ablation (and other names and similar methods).49This treatment approach might seem simplistic and destructive and maybe even a Very Bad Idea … and you could be right. Certainly it’s understudied, but it has produced some seemingly promising results for some conditions, including tennis elbow.5051 But those are more examples of uncontrolled studies. Such “circumstantial evidence” is better than nothing, but it’s really not great. And that’s all there is on this topic.

And of course there are some reasons why denervation might not work in principle, and ways that it could go wrong.52 But it is generally simpler and less potentially destructive than other surgeries, and if you are going to consider any surgery, you might consider starting with this one.Shock wave therapy for tennis elbow

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) is the more expensive, intense, and high-tech and over-hyped cousin of regular therapeutic ultrasound. ESWT uses much stronger sound waves — shock waves! Treatment is painfully intense and painfully pricey, though it would probably be worthwhile if it worked.

On the one hand, ESWT is just a “more is better” version of standard ultrasound, because it is often used with the same imprecise clinical intention to stimulate/provoke tissues. On the other hand, because it was originally developed for smashing gall stones, ESWT is strong enough to actually disrupt tissue, such as, say, calcifications in tendons — which is a nice precise clinical goal and a whole different kettle of fish. And there is evidence that it can be effective in exactly that circumstance: if your tendons are calcifying.

Unfortunately, the evidence strongly suggests that it just doesn’t seem to work for most tendinitis, probably because there’s not much calcifying going on.

This was settled quite a while ago. A biggish review of nine studies produced “platinum” level (better than gold!) evidence that “ESWT provides little or no benefit in terms of pain and function in lateral elbow pain.”53 That’s right: platinum negative evidence. The negativity was echoed by another review in 2007.54

Despite the years flying by, nothing important has changed since — still just a handful of small trials, nothing that changes those early reviews. Indeed, they just pile on, re-stating that there aren’t enough good quality studies, and what we have is only weakly positive at best.55 ESWT almost certainly does not clearly work well for the average case of tennis elbow. •sad trombone•

Regenerative medicine for tennis elbow (mainly platelet-rich plasma)

There are some emerging high-tech treatments intended to stimulate/accelerate tendon tissue growth. These are exciting possibilities, but I think you should save your money for now.

This website has a salamander for a mascot/logo because that critter has genuinely amazing powers of regenerative healing. We know it’s possible because salamanders do it: the only macroscopic animal with that superpower.

But we certainly don’t have it yet. We’ll probably get some real regenerative medicine eventually, but it’s still early days. Meanwhile, there are several companies racing to market on this. Their value can only be based on hype, because none of them have been adequately tested yet. Tendoncel is the most prominent I know of, and by their own admission they are still testing their product.

There’s also platelet-rich plasma injection — basically, injecting a sauce of your own platelets — which is a poor man’s version of stem cell therapy, less new, and less promising. Despite widespread claims of efficacy, the evidence is extremely weak sauce.5657 I cannot recommend PRP at this time. I review that topic in detail in a separate article: Does Platelet-Rich Plasma Injection Work? An interesting treatment idea for arthritis, tendinopathy, muscle strain and more.

So there’s just no basis for confidence about any regenerative therapy for tendons at this time. It’s implausible on its face, because there are extremely few precedents for clearly successful regenerative medicine in humans, and many conspicuous failures.

That doesn’t mean it won’t work, but it does mean that the bar for the evidence is very high, and even if we see evidence of efficacy soon, it will definitely still not be enough: it will have to be replicated independently.

So, as of 2022, we’re a ways off yet — probably years off.

Strengthening

Exercise is the closest thing there is to a miracle cure for anything, and building strength slowly (progressive training) is a staple of rehab … for both good and bad reasons. Let’s deal with the problems first, before moving on to the good news:

- Rampant oversimplification to “just strengthen it.” More nuanced load management over time is what is always actually needed. The oversimplification especially tends to lead to problem #2…

- Overdoing it, especially in no-pain-no-gain North America. This can be especially problematic with repetitive strain injury, where overuse is — by definition — the main cause of trouble in the first place. Aggressive strengthening for an overuse injury may be like trying to put out a fire with a flame thrower.

- There’s too much weight placed (pun intended) on the power of specialized, specific strengthening exercises to “correct” allegedly faulty biomechanics.

In the case of tendinitis specifically, there’s a fourth issue:

- Too much hype about eccentrics and isometrics. “Eccentric” training is using braking contractions to stimulate tendon healing (like your biceps while lowering a weight). “Isometric” training is contraction without movement (clenching). Much more on both below.

Despite all that, strengthening almost certainly still does have an important role to play in recovery from tennis elbow. It’s just important to avoid the problems: curb your enthusiasm and expectations, pace yourself in general, and especially go slow at first.

Strengthening may seem more effective for tennis elbow than some other tendinitis (e.g. Achilles tendinitis) because it often isn’t a “pure” case of tendinitis, but involves more muscle fatigue and discomfort — which is easier to recover from in general, and perhaps more likely to respond to exercise. Raman et al.: “Strengthening … is effective in reducing pain and improving function for lateral epicondylosis but optimal dosing is not defined.”58 Whatever the optimal dosing is, it’s probably not “go hard or go home.”

How to strengthen wrist extensors

Exercising the muscles of the arm is both hard and easy. It’s easy in the sense that the motion is straightforward, and there are convenient ways to challenge your wrist muscles from the comfort of your own home. Or bed, even!

But it’s “hard” because wrist extension is a feeble, tiny motion that doesn’t feel satisfying because you can’t really “do” much with it. You won’t be bragging at the office about how much you were “torquing” with your wrists at the gym.

Just how powerfully can you extend your wrist? What can you lift on the back of your hand? If you place your forearm and hand flat on a tabletop and lift just your hand… how strongly can you do that? Most people can only exert about 6 Newton-Metres of extension torque,59 barely more than half the oomph we can muster with wrist flexion (which isn’t exactly a powerful motion either).

Newton-Metres? Say what? That is the equivalent of lifting roughly 4 lbs. That’s right: most people would struggle to lift a kitten with their wrist extension. “Weak as a kitten.” Sort of.

Simple wrist extensions. Extend your wrist while holding a small weight like a can of soup, an adorable little barbell, or the even more adorable aforementioned kitten. Initially, I recommend doing this while standing with your arms pointed straight down, so that your wrist starts the lift from a straight position, like so. Later on, you can make it more difficult by holding your forearm level, so that you’re lifting your weight through a full range of motion, from fully flexed to fully extended, like so:

I have deliberately demonstrated this exercise with a very light bottle of water, to emphasize the fact that you can and should make this as easy as possible at first. It’s amazingly easy to wear out these muscles, even with an extremely light weight. Obviously you can adjust the difficulty to suit your needs, but please do err on the side of “no big deal,” especially in the early stages.

Wrist rolling is another option, quite different, and hard to describe. A quick video is by far the easiest way to understand the exercise:

Rollers are available at most gyms (and not used much), but you can also easily make your own with three ingredients:

- a couple feet of broom handle or equivalent — any cylinder you can get a decent grip on with two hands

- a few feet of study cord or thin rope

- a weight that you can tie the cord to

Tie the cord firmly to the center of the stick at one end, and to the weight at the other. Stand holding the roller, turn the roller a few times to start winding the cord around it until you’ve taken up the slack… and then wind up your weight!

You will undoubtedly have to experiment with weight and dosage. It’s impossible to prescribe even an approximate standard weight for this, because it’s actually quite a complicated physics equation (leverage, the diameter of the spool, etc). This exercise has a very different feel than just a few lifts of the wrist with a weight — you’ll just have to experiment with a weight that feels right to you, once again erring on the side of “easy.”

Saucepans make a surprisingly good wrist extension dumbbell. The biomechanics work rather nicely. Most people have pans of various sizes and weights. The load can be nicely varied simply by shifting the grip up or down the handle.

Perhaps a product dedicated to wrist strengthening? Not necessary, but perhaps enjoyable and helpful. The TheraBand FlexBar is a good example of a convenient exercise tool for the forearm muscles. It’s basically just a sturdy rubber stick, about the size and shape of a paper-towel tube, that you twist back and forth. An extra long silicone dildo would work just as well (admit it, you were getting bored until you got to this sentence). Nothing to it.

The claims of the manufacturer notwithstanding, I do not think this is substantively different from any other method — if you’re resisting wrist extension by any means, you’re doing the job. But it is handy.

Eccentric training for tennis elbow

An eccentric contraction is just a contraction while lengthening, also sometimes called a braking contraction, and we use them all the time. The canonical example of an eccentric contraction is the biceps while lowering a dumbbell: the muscle is lengthening, but it’s also clenching to control how fast it lengthens. Concentric contractions are the opposite: they simultaneously contract and shorten the muscle.

The overhyped claim: Eccentric contractions somehow stimulate tendon healing more than concentric contractions do.

The disappointing reality: There’s probably no magical therapeutic difference between eccentric and concentric contractions.

Eccentric contraction is probably just more efficient than concentric (harder work for less energy), and causes more soreness. In other words, eccentric contractions will wear a muscle out faster. It’s more of a stimulus. But how much stimulus do we really need anyway? Especially for an overuse injury? If anything, we want to be cautious not to overdo it!

| concentric contraction | = | contraction while shortening |

| isometric contraction | = | contraction without changing length (“clenching”) |

| eccentric contraction | = | contraction while lengthening (“braking”) |

In most strength-training exercises and natural and functional movements, eccentric contractions are naturally paired with concentric contractions. What goes up (concentric) must come down (eccentric).60 To isolate eccentric contraction, you would have to only lower the weight — which is just awkward!61 Surely this has been tested, so what does the research say?

The problem with most research into this question is that eccentric training only has rarely been compared to normal combined contractions (concentric one way, eccentric the other). So I am grateful for one 2017 study that actually did, a small but properly controlled study of 34 people in three groups:62

- eccentric contraction only

- concentric + isometric contraction (clenching without movement)

- eccentric + concentric contraction (also known as “normal contraction”)

Everyone did five sessions of training per week for a month. The eccentric group did not win. Mixing in isometric did not win. The eccentric+concentric group did win — also known as the normal-contractions group. Case closed. There might be a small eccentric training benefit for some people, but it’s not worth the hassle. Sensible load management is probably way more important on average.

Are isometric contractions a pain-killer? Maaaaybe

Iso-what? Isometric contractions are non-moving contractions, “clenching” contraction: contracting without movement. In the case of tennis elbow, that would be tensing the muscles on the back of the forearm without wrist motion. Isometrics are not great for building strength (maybe a modest training effect if you did a lot of it).

But what if it had some sensory effects? What if it could reduce pain? That could be handy.

The overhyped claim: Isometrics are pain-killing and a great way to work on your tendinopathy while remaining active.

The disappointing reality: While it’s probably worth further study, there is no clear, strong signal here, certainly nothing that can be applied to all kinds of tendinitis, and there are strong reasons for doubt and concern.

The clenching-as-a-pain-killer story begins with a 2014 paper in Sports Medicine which pointed out the glaringly poor correlation between symptoms and actual tissue trouble in tendinopathy. The authors suggested that the pain might, perhaps, be tamed by neurological modulation, by putting the focus on changing how it feels (not on the state of degeneration). Perhaps we can “tune” the sensitivity of distressed tendons by using it in ways that are stimulating-yet-safe.63

They followed up with a small 2015 science experiment that showed what seemed to be a robust pain-relief effect on another tendinopathy (patellar) just from clenching for a minute.64 The pain reduction was noteworthy and lasted for at least 45 minutes. This study had some big names attached to it, so it was taken seriously and shared and cited widely. Everyone loves good news! And any evidence of an actual pain-killing effect from something as easy as clenching definitely qualifies as good news — great news, even. There were two follow-up trials, both positive in different ways: Rio et al. reported that isometrics delivered “greater immediate analgesia,”65 and van Ark et al. declared isometrics to be more excellent than eccentrics on average:66

This is the first study to show a decrease in patellar tendon pain without a modification of training and competition load and the first study to investigate isometric exercises in a clinical setting.… easy-to-use exercises that can reduce pain from patellar tendinopathy for athletes in-season.

Kind of a big deal, if true! Worthy of hype, perhaps?

The other side of the isometrics story

Although those studies were popular, they didn’t persuade everyone: the effect sizes were modest, they were too small, they were not ideally designed to really settle the question, and they all came from the same lab. There are caveats about their results that make them harder to get excited about.67

Another research group failed to find the same thing — and not just a similar study, but a formal replication attempt.68 In 2019, the British Journal of Sports Medicine politely called it a bunch of hype:69

Adopting new management approaches without adequate evidence is problematic, especially when this is inconsistent with prevailing evidence that tendons require time to adapt to adequate and appropriate loading.

Even if isometrics actually do work great for patellar tendinopathy and are vindicated by future research, it’s clearly not wise to extrapolate to other tired tendons. For instance, a tiny 2018 trial of isometrics for Achilles tendinitis came up empty.70 And so did another one for plantar fasciitis.71 Tendinitises do have a lot in common, but they are definitely not all the same.

What about isometric training for tennis elbow specifically?

There’s barely any evidence, but it’s not good news either. In 2016, a study of tennis elbow specifically also failed to reproduce the isometric pain-killing effect.72 In this test, pain was either unaffected or actually worsened (with the strongest isometric contractions). Boo! It’s also worth pointing out that, in Stasinopoulos et al. (cited above), the isometrics were outperformed by bog-standard strength training for tennis elbow. It wasn’t a direct test of isometrics alone, but it certainly contributes, and it was about this condition.

So it’s not very promising, and this is a classic example of mixed but generally inadequate and unimpressive evidence. Such an easy thing still seems easy and perhaps worth a try. The risk of exacerbation seems minor, but — as the BJSM editorial wisely implied — if it’s not actually beneficial then it’s likely to just lead to pre-empting exercise dosage caution. In theory one could be keen to try isometrics and sensible about dosage, but in practice I suspect the hype mostly just convinces people to throw out the load management rulebook and “get serious” about training with isometrics — which either have no benefit at all, or a minor benefit that is drowned out by overdoing it.

How to isometrically contract the wrist extensors

If you must, there’s nothing to it. It’s probably most effective to block extension with your other hand, or against a surface like the underside of a desk. Start with a moderate intensity for about one minute, and tinker with the intensity and duration to see what works best for you.

About Paul Ingraham

I am a science writer in Vancouver, Canada. I was a Registered Massage Therapist for a decade and the assistant editor of ScienceBasedMedicine.org for several years. I’ve had many injuries as a runner and ultimate player, and I’ve been a chronic pain patient myself since 2015. Full bio. See you on Facebook or Twitter., or subscribe:

Appendix: A story about pain relief from doing the most painful thing

This is a personal rehab story, just a yarn about my running battle with a weird case of tennis elbow, and how I’ve achieved some success by … doing what hurt the most: lifting pots! Saucepans. Of all things. A couple caveats though:

- I truly am not sure that this is really tennis elbow. It is unquestionably similar, but the diagnosis is in doubt.73

- No sooner had I written this than the pattern started to break, and the results I’d been so amazed by got less reliable.

But it’s still interesting.

Whatever is going on — still now as I write this — it is severe. My elbow/arm is really messed up. The situation has been slowly worsening for about a year. It was just an erratic annoyance until the spring of 2024. Since then it has steadily ramped up, becoming intense and stubborn even by my rather exotic standards. Because of my bigger health issues, I’ve had some some chronic pains that were whoppers, but this is the whopperiest so far.

Originally the pain seemed like elbow arthritis: morning aches in the joint. Over time, it spread into the forearm and started to seem more like an odd case of tennis elbow. So, when things first got bad, I just tried to “take it easy,” my reflexive response to any new pain, and especially one that might be related to repetitive strain. But it just kept getting worse! So …

I decided to do more of what hurts

To fly right into the storm. Maybe the way out is through. I would overuse my overuse injury … if that’s what it is.

Lifting pots and pans has always been nasty, so pots and pans became my forearm barbells: lifting them like a cook slowly flipping a pancake, over and over again. (Not eccentric or isometric.74)

Two hours after lifting pots, I could still pot-lift painlessly. Amaze amaze amaze!

I was doing what seemed like the worst possible thing to do, but it felt like the best. Yahtzee?

Nopezee!

Like Groundhog Day for chronic pain

My elbow challenge gets a reset every day. The pain always comes back within a few hours, and usually worse.

I can always beat it back with more pot-lifting — but less effectively each time, and it’s futile late in the day.

Then things calm down while I sleep and it starts all over again.

The analgesia I’m getting from doing the most painful thing I can think of is real and substantive, better than anything I have gotten from ibuprofen or Voltaren, icing or heating or both (contrasting), stretching, massage therapy, spicy ointments, and more. I’m slowly working through all the options (with very low expectations).

After many weeks of pot-lifting, I think it’s safe to conclude that it’s (a) very useful, but (b) also not actually solving the problem.

Why do I get such strong relief from something that is so painful at first? Why would anyone? We all wish I could explain that. And I could speculate for 2000 words — I do have ideas7576— but it would be a poor value, just a wordy version of “I really haven’t got a clue.”

What’s new in this article?

Eleven updates have been logged for this article since publication (2010). All PainScience.com updates are logged to show a long term commitment to quality, accuracy, and currency. more

When’s the last time you read a blog post and found a list of many changes made to that page since publication? Like good footnotes, this sets PainScience.com apart from other health websites and blogs. Although footnotes are more useful, the update logs are important. They are “fine print,” but more meaningful than most of the comments that most Internet pages waste pixels on.

I log any change to articles that might be of interest to a keen reader. Complete update logging of all noteworthy improvements to all articles started in 2016. Prior to that, I only logged major updates for the most popular and controversial articles.

See the What’s New? page for updates to all recent site updates.

Oct 25, 2024 — Added a “story about pain relief from doing the most painful thing,” which was just simple strength training.

2021 — Thorough proofreading, correcting an unusual number of minor errors — not surprising after the huge recent update.

2021 — Complete article reboot and expansion, roughly tripling in length to about 15,000 words. The most substantively upgraded sub-topics are etiology and risk factors, recovery time, steroids, denervation, massage, and strengthening.

2020 — General editing, and a new section, “Some important general treatment principles to bear in mind.”

2019 — New section: “Medications for tennis elbow.”

2018 — Update on isometric contraction for pain control, citing Coombes et al.

2015 — Isometric contraction for pain control, based on Rio.

2015 — Added information about ESWT ultrasound.

2014 — General editing and more details throughout first half. New section about exercise. Improved description of forearm mobilizations.

2014 — Traffic to this article has increased sharply, so I gave it some love: a thorough general upgrade. I particularly clarified icing rationale and diagnosis.

2013 — Added surgery section with fascinating results of placebo surgery.

2010 — Publication.

Notes

- Boyer MI, Hastings H2. Lateral tennis elbow: "Is there any science out there?". Journal of Shoulder And Elbow Surgery. 1999;8(5):481–491.

- We can put a man on the moon, but we can’t treat chronic pain. The science and treatment of pain and injury was neglected for decades while medicine had bigger fish to fry, and it remains a backwater to this day. The seemingly simpler “mechanical” problems of injury and rehab have proven to be surprisingly weird and messy. Oversimplification and quackery still dominate the field. For more information, see A Historical Perspective On Aches ‘n’ Pains: Why is healthcare for chronic pain and injury so bad?

- Descatha A, Albo F, Leclerc A, et al. Lateral Epicondylitis and Physical Exposure at Work? A Review of Prospective Studies and Meta-Analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016 11;68(11):1681–1687. PubMed 26946473 ❐

This large, high quality meta-analysis confirmed that overuse in the workplace is a major risk factor for tennis elbow. The five studies they analyzed collectively followed thousands of people, identifying 256 cases. Workers who do “strenuous manual tasks involving the elbow and/or hand with a combination of force and posture” are roughly 2-3 times more likely to develop elbow pain than workers who don’t. The data “strongly support the hypothesis of an association between biomechanic exposure involving the wrist and/or elbow at work and incidence of lateral epicondylitis.”

- Kryger AI, Andersen JH, Lassen CF, et al. Does computer use pose an occupational hazard for forearm pain; from the NUDATA study. Occup Environ Med. 2003 Nov;60(11):e14. PubMed 14573725 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 51716 ❐ This is one of the best of just a few sources on this topic, a study of more than 6000 people doing “a wide range of computer use.” The results were a bit “yes and no,” and it’s also rather old — which is relevant here, because computer usage has definitely changed since the early 2000s, and a “wide range of computer use” back then was probably quite different than it is now. A lot of people were still just getting going with email back then. They found both that “intensive” use of mouse and keyboard were “the main risk factors for forearm pain.” But they also concluded that it was rarely serious: “not commonly associated with any severe occupational hazard.”

- Mikkelsen S, Lassen CF, Vilstrup I, et al. Does computer use affect the incidence of distal arm pain? A one-year prospective study using objective measures of computer use. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2012 Feb;85(2):139–52. PubMed 21607699 ❐ This study reported that, in more than 2000 people over the course of a year, mouse usage was linked to acute pain, but not keyboarding, and neither one was “related to the development of prolonged or chronic pain.” It was a particularly good little study in many ways (prospective!), but it had an acknowledged major limitation: “low keyboard times.” They didn’t study people who type a lot, so it was like studying running injuries in “runners” who don’t actually run all that much. Their “computer workers” didn’t actually type all that much! So this only established that light keyboarding isn’t much of a risk factor, and that mousing can definitely cause trouble but isn’t particularly a risk for stubborn trouble.

- This is a working theory for me. There is no clear evidence that confirms it. But this isn’t just a reflexive acknowledgement that I’m speculating: while there’s not really any doubt that computer users can develop persistent arm pain, it’s an open and interesting question whether or not the physical strain of keyboard and mouse usage is actually the problem. There are almost certainly other factors, and some surprising ones. More on this to come.

- I am Canadian, and in this part of the world manual labour is dramatically rarer than it was a hundred years ago. But I am sure there are a lot of places around the world where workers are injuring their elbows doing all kinds of repetitive work with their hands, and computer use isn’t such an overwhelmingly dominant source of risk.

“Tendinitis” versus “tendonitis”: Both spellings are acceptable these days, but the first is the more legitimate, while the second is just an old misspelling that has become acceptable only through popular use, which is a thing that happens in English. The word is based on the Latin “tendo” which has a genitive singular form of tendinis, and a combining form that is therefore tendin. (Source: Stedmans Electronic Medical Dictionary.)

- One of the best example is the formal name of frozen shoulder, “adhesive capsulitis,” which was named based on the assumption that the shoulder joint capsule gets inflamed and then literally gets stuck. It doesn’t. It actually shrinks, so it should be called, perhaps, contractive capsulitis. But names get stuck. Pun intended, of course. There are many other examples like this in musculoskeletal medicine: it’s practically standard for the names of conditions to reflect some early wrong idea about of the nature of the beast.

- Millar NL, Hueber AJ, Reilly JH, et al. Inflammation Is Present in Early Human Tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med. 2010 Jul. PubMed 20595553 ❐

- Andres BM, Murrell GAC. Treatment of tendinopathy: what works, what does not, and what is on the horizon. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(7):1539–1554.

- Dakin SG, Newton J, Martinez FO, et al. Chronic inflammation is a feature of Achilles tendinopathy and rupture. Br J Sports Med. 2017 Nov. PubMed 29118051 ❐

This paper now stands as the best available evidence so far that rumours of inflammation’s demise in tendinopathy are exaggerated/oversimplified. There are no other important sources I’m aware of so far (as of early 2020), and Dakin et al. cite only their own evidence on this.

- Khan KM, Cook JL, Taunton JE, Bonar F. Overuse tendinosis, not tendinitis, part 1: a new paradigm for a difficult clinical problem (part 1). Phys Sportsmed. 2000;28(5):38–48. PubMed 20086639 ❐

- Young CS, Rutherford DS, Niedfeldt MW. Treatment of Plantar Fasciitis. Am Fam Physician. 2001 Feb 1;63:467–74. PainSci Bibliography 56910 ❐ Such degeneration is “similar to the chronic necrosis of tendonosis, which features loss of collagen continuity, increases in ground substance (matrix of connective tissue) and vascularity, and the presence of fibroblasts rather than the inflamatory cells usually seen with the acute inflammation of tendinitis.”

- Heinemeier KM, Øhlenschlæger TF, Mikkelsen UR, et al. Effects of anti-inflammatory (NSAID) treatment on human tendinopathic tissue. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2017 Nov;123(5):1397–1405. PubMed 28860166 ❐

- Soligard T, Schwellnus M, Alonso JM, et al. How much is too much? (Part 1) International Olympic Committee consensus statement on load in sport and risk of injury. Br J Sports Med. 2016 Sep;50(17):1030–41. PubMed 27535989 ❐

This is the first of a pair of papers (with Schwellnus) about the risks of athletic training and competition intensity (load). Is load a risk for injury and illness? How much is too much? Is too little a problem? These papers were prepared by a panel of experts for the International Olympic Committee, and both them use many words to say the same things formally — but they are good points. Here they are in plain English:

- There’s not enough research, surprise surprise, and what we do know is mostly from limited data about a few specific sports. But there’s enough to be confident that “load management” overall is definitely important.

- Both illness and injury seem to have a similar relationship to load — lots of overlap.

- Too much and not enough load probably increase the risk of both injury and illness. You want to be in the goldilocks zone! But the devil is in the details …

- Not everyone is vulnerable to high load, and elite athletes are the most notable exception: they are relatively immune to the risks of overload, probably because of genetic gifts. Everyone else gets weeded out!

- Big load changes — dialing intensity up or down too fast — are much bigger risks than absolute load. If you methodically work your way up to a high load, it may even be protective.

- “Load” can also refer to non-sport stressors and “internal” loads, which are legion. Psychology, for instance, probably does matter: anything from daily hassles to major emotional challenges, as well as stresses related to sport itself.

- Lassen CF, Mikkelsen S, Kryger AI, Andersen JH. Risk factors for persistent elbow, forearm and hand pain among computer workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2005 Apr;31(2):122–31. PubMed 15864906 ❐ This 2005 paper “examined the influence of work-related and personal factors on the prognosis of ‘severe’ elbow, forearm, and wrist-hand pain among computer users.” And it found not a heck of a lot. Time pressure, being a woman, and being highly motivated were predictors, but otherwise “the prognosis seemed independent of psychosocial workplace factors and personal factors.” There was just one clear predictor of persistent arm pain: “pain in other regions.” Which strongly implies that systemic conditions have more to do with how bad your tennis elbow will be than anything specific you are doing with your arms.

- Shiri R, Viikari-Juntura E, Varonen H, Heliövaara M. Prevalence and determinants of lateral and medial epicondylitis: a population study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006 Dec;164(11):1065–74. PubMed 16968862 ❐

- Cannon DE, Dillingham TR, Miao H, Andary MT, Pezzin LE. Musculoskeletal disorders in referrals for suspected cervical radiculopathy. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2007 Oct;88(10):1256–9. PubMed 17908566 ❐

This study of 190 patients with cervical radiculopathy (irritated nerve roots) showed that they have a higher prevalence of other kinds of musculoskeletal conditions, things like lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow), de Quervain's tenosynovitis (a tendinitis-like problem in the thumb).

There are two distinct possibilities here, and they could also overlap to some extent:

- The “tennis elbow” might just be a symptom of radiculopathy, elbow and arm pain, misdiagnosed as tennis elbow.

- Or impaired nerve function to the arm has effects we do not understand on tissue vulnerability, and tennis elbow is actually a pathological long-term consequence.

- Aben A, De Wilde L, Hollevoet N, et al. Tennis elbow: associated psychological factors. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018 Mar;27(3):387–392. PubMed 29433642 ❐ Psychological traits in 69 tennis elbow patients, compared to healthy people, showed that tennis elbow patients score poorly for extraversion and agreeableness, high for perfectionism, and are at greater risk for anxiety/depression. Their workload was higher and they had less work autonomy (though general job satisfaction was fairly high in both groups in this case). This was far from a perfect study, but there’s not much data on this topic, and it’s certainly suggestive.

- Modern pain science shows that pain is as hard to predict or control as the weather, a function of countless chaotic variables, surprisingly disconnected from seemingly “obvious” causes of pain. Pain is jostled by many systemic variables, but especially by the brain’s filters, which thoroughly “tune” pain and often even overprotectively exaggerate it — so much so that sensitization can get more serious and chronic than the original problem. This has complicated all-in-your-head implications: if the brain controls all pain, does that mean that we can think pain away? Probably not, but we do have some neurological leverage — maybe we can influence pain, if we understand it. See Pain is Weird: Pain science reveals a volatile, misleading sensation that comes entirely from an overprotective brain, not our tissues.

- Cannon 2007, op. cit.

- Of course I do not mean to minimize a fierce case of tennis elbow, as it can get quite unpleasant. That said, it’s just not in the same league as a bad case of gout, the early stages of frozen shoulder, polymyalgia rheumatica, a toothache, severe back pain, and so on. If your elbow pain is severe enough to, say, keep you awake at night, there might be more going on than tennis elbow.

- The risk factors are probably both biological and behavioural: some people are probably just more prone to overdoing it, which likely accounts for a significant percentage of the cases that go poorly.

- Bittermann A, Gao S, Rezvani S, et al. Oral Ibuprofen Interferes with Cellular Healing Responses in a Murine Model of Achilles Tendinopathy. J Musculoskelet Disord Treat. 2018;4(2). PubMed 30687812 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 52446 ❐

- Heinemeier KM, Øhlenschlæger TF, Mikkelsen UR, et al. Effects of anti-inflammatory (NSAID) treatment on human tendinopathic tissue. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2017 Nov;123(5):1397–1405. PubMed 28860166 ❐

- FDA.gov [Internet]. Acetaminophen and Liver Injury: Q & A for Consumers; 2009 Jun 4 [cited 16 Aug 31]. PainSci Bibliography 53431 ❐

“This drug is generally considered safe when used according to the directions on its labeling. But taking more than the recommended amount can cause liver damage, ranging from abnormalities in liver function blood tests, to acute liver failure, and even death.”

- Bally M, Dendukuri N, Rich B, et al. Risk of acute myocardial infarction with NSAIDs in real world use: bayesian meta-analysis of individual patient data. BMJ. 2017 May;357:j1909. PubMed 28487435 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 53592 ❐

Taking any dose of common pain killers for as little as a week is associated with greater risk of heart attack, according to this meta-analysis, and the risk is greatest in the first month of use. This is probably primarily of concern for people already at risk for heart attack, but this data doesn’t address that question, and it’s a lot of people regardless.

- Derry S, Moore RA, Gaskell H, McIntyre M, Wiffen PJ. Topical NSAIDs for acute musculoskeletal pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;6:CD007402. PubMed 26068955 ❐

- Oral corticosteroids kill pain in a big way, no doubt about it, but have complex and serious side effects so serious that they are even more verboten for regional body pain than the notorious opioids.

- Bisset L, Beller E, Jull G, et al. Mobilisation with movement and exercise, corticosteroid injection, or wait and see for tennis elbow: randomised trial. BMJ. 2006 Nov;333(7575):939. PubMed 17012266 ❐

- Tonks JH, Pai SK, Murali SR. Steroid injection therapy is the best conservative treatment for lateral epicondylitis: a prospective randomised controlled trial. Int J Clin Pract. 2007 Feb;61(2):240–6. PubMed 17166184 ❐

“On the basis of the results of this study, the authors advocate steroid injection alone as the first line of treatment for patients presenting with tennis elbow demanding a quick return to daily activities.”

- Orchard J, Kountouris A. The management of tennis elbow. BMJ. 2011;342:d2687. PubMed 21558359 ❐ Orchard and Kountouris concluded in a 2011 review of tennis telbow treatments that “Cortisone injections are harmful in the longer term and are no longer recommended in most cases.” Not everyone agrees, but it’s an important opinion to take note of.

- Khan KM, Cook JL, Bonar F, Harcourt P, Astrom M. Histopathology of common tendinopathies. Update and implications for clinical management. Sports Med. 1999 Jun;27(6):393–408. PubMed 10418074 ❐

It is clear that corticosteroid injection into tendon tissue leads to cell death and tendon atrophy. As tendinosis is not an inflammatory condition, the rationale for using corticosteroids needs reassessment, as corticosteroids inhibit collagen synthesis and decrease load to failure.

- Lewis M, Hay EM, Paterson SM, Croft P. Local steroid injections for tennis elbow: does the pain get worse before it gets better? Results from a randomized controlled trialorse before it gets better? Results from a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Pain. 2005;21(4):330–4. PubMed 15951651 ❐

- Coombes BK, Connelly L, Bisset L, Vicenzino B. Economic evaluation favours physiotherapy but not corticosteroid injection as a first-line intervention for chronic lateral epicondylalgia: evidence from a randomised clinical trial. Br J Sports Med. 2016 Nov;50(22):1400–1405. PubMed 26036675 ❐

- Stretching is not a pillar of fitness: it isn’t a good warm-up, and it doesn’t enhance peformance, and it won’t prevent or treat soreness or injury. But it can cause injuries, and it can impair performance (slightly). It will boost flexibility, for whatever that is worth — which is surprisingly little (even for most athletes). Many major muscles are just mechanically impossible to stretch in the first place. Stretch might help some kinds of pain, like muscle pain, but stretching is clearly not of much help to most chronic pain patients. There is no “advanced” stretching method that overcomes any of these limitations, but you can spend a lot of money on books and courses and certifications — stretching is surprisingly big, snake oil. But, yes, it does feel good. See Quite a Stretch: Stretching science has shown that this extremely popular form of exercise has almost no measurable benefits.

- Collins NC. Is ice right? Does cryotherapy improve outcome for acute soft tissue injury? Emerg Med J. 2008 Feb;25(2):65–8. PubMed 18212134 ❐

This is a 2008 review of just 6 studies of therapeutic icing, only two of them any good: one with slightly positive results, the other showing no effect. So that’s two studies that showed little or no benefit, which is leaning towards bad news, but it’s just not enough data to clinch it. (Four animal studies showed reduced swelling, but we can’t take animal studies to the bank.) The bottom line is just that “there is insufficient evidence.”

- Ajimsha MS, Chithra S, Thulasyammal RP. Effectiveness of myofascial release in the management of lateral epicondylitis in computer professionals. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012 Apr;93(4):604–9. PubMed 22236639 ❐

68 patients suffering from lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow) were divided into two groups. Some received myofascial release, the rest a sham ultrasound therapy. The results for MFR were quite a lot better: almost 80% improvement after a month, compared to just 7% for the sham ultrasound. The benefit was generally lasting.

These results confirm my bias — this is the result I’d expect based on my own experiences and beliefs — but it’s also obvious that they have a little bit of “too good to be true” going on. Results this good are basically unheard of in musculoskeletal medicine. There’s also no guarantee that the experiment was actually good quality, despite the lack of any obvious problems.

- Travell J, Simons D, Simons L. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual. 2nd ed. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 1999.

The “big red books” by Drs. Janet Travell and David Simons are a two-volume set of texts about so-called trigger points and myofascial pain syndrome. Early versions and editions were extremely influential in world of massage and physical therapy starting in the 1980s and continuing well into the 21st Century. Arguably the are the most influential texts in that field.

The introductory chapters present a good overview of the subject, if somewhat technical and now quite dated. The books are brilliantly illustrated, for what it’s worth, and those drawings will probably influence the field for decades to come, the compelling iconography of a clinical paradigm.

Although a landmark work, more recent information has been published in Muscle Pain: Understanding its nature, diagnosis and treatment by Siegfried Mense and David Simons, and there are many reasonable questions and doubts about almost everything Travell and Simons thought and wrote about this topic “back in the day.”

Volume 1, p513. “Scalene muscle trigger points are frequently the key to [treatment of] forearm extensor digitorum trigger points.” This is an expert opinion, of course, not “evidence.” - Loew LM, Brosseau L, Tugwell P, et al. Deep transverse friction massage for treating lateral elbow or lateral knee tendinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;11:CD003528. PubMed 25380079 ❐