Deep Friction Massage Therapy for Tendinitis

A guide to a simple self-massage technique sometimes helpful in treating common tendinitis injuries like tennis elbow or Achilles tendinitis

Can strumming a tendon like a guitar string treat tendinitis?

If you have tendinitis, or a closely related problem, you may be able to accelerate healing with a self-massage technique called “frictioning” or “deep friction massage.”1 This has been a popular and widely used treatment method for decades now.2 Its efficacy is unproven and it is effectively still experimental,3 but it may be appropriate to use in cases of:

- supraspinatus tendinitis, on the “tip” of the shoulder

- tennis elbow or tendinitis of the common flexor or extensor tendons of the forearms, just below the elbow on the outside

- Achilles tendinitis, on the back of the heel and in the Achilles tendon

- DeQuervain’s tenovaginitis, along the thumb-side of the wrist

Friction massage “scrubs” the fibres of the tendon, theoretically aiding recovery, and it doesn’t really have to be particularly “deep” (intense). If it works, the mechanism is probably just mild stimulation of natural tissue repair processes. Friction massage is well worth trying, because it’s quite safe, basically free to experiment with, and makes some sense even though it’s far from proven medicine.4

After many months of persistent discomfort and limited range of movement, and after my third cortisone shot for thumb tendinitis and still no relief, I went searching and found your article about friction massage. I began the friction massage, and now, three days later, the discomfort is almost entirely gone! I'll continue with this for a while and see if I can eliminate it altogether. In the meantime, I shall once again pick up my violin, and play a tune of thanks for you!

Eloise Brandt, violinist

How to do friction massage

The method is inconsistent in the wild.5 I will try to provide some guidelines that split the differences. Friction massage is distinctive — it has a different goal and feel than the more typical squeezing and steam-rolling of muscles, as you might do with some tennis ball massage. But the action of friction massage is simple and well-suited to self-treatment, as long as you can reach the problem (and most tendinitis is reachable). Just rub gently back and forth over the inflamed tendon at the point of greatest tenderness. Your strokes should be perpendicular to the fibres of the tendon — like strumming a guitar string.

Use gentle to moderate pressure with the pads of your fingers or a thumb. Strong pressure is not required or wise, particularly for self-treatment. I’ll explain more about intensity as we go.

Even gentle friction massage will cause discomfort — you are rubbing an active case of tendinitis, after all! The pain should be clear and a bit burning or sharp — however, the discomfort should be easily bearable.

If the frictioning is painless, or the pain is dull, you are probably in the wrong place, or you don’t have tendinitis. If it is too painful, either you are pressing too hard, or the tendinitis is simply too serious to easily treat in this fashion.

The discomfort will subside significantly after one or two minutes. If it doesn’t, stop the treatment and try again later. If the tenderness does subside, increase the intensity until it returns. Wait for it to subside again. And increase it a third time, and wait a third time for the tenderness to ease. Like this:

- Friction for 1–2 minutes until sensitivity subsides.

- Increase intensity slightly. Friction for 1–2 minutes until sensitivity subsides.

- Increase intensity slightly. Friction for 1–2 minutes until sensitivity subsides.

Finish by icing the massage site, ideally with bare ice (for safety, ice only for a maximum of about two minutes, or until the spot is numb, whichever comes first). For more information about therapeutic icing and ice massage, see Icing for Injuries, Tendinitis, and Inflammation.

The complete treatment should take about 3-6 minutes, and should be done at least once per day, and a maximum of three times per day. If it’s going to work, you should feel immediate improvement in symptoms following each treatment. It may not work for you! This is no miracle cure. It is worth trying, but it fails in many cases for all kinds of reasons.

Friction massage treatments should be wrapped up by cooling the area down with an application of raw ice.

How friction massage works (if it works)

Friction massage is in theory a very specific way to “use it or lose it” — to stimulate enough, but not too much.

A basic principle of healing is that overloaded tissue must be given a bit of a break from their labours, and this is particularly true of tendinitis, where stress has already exceeded the capacity to adapt. Equally true, total stagnancy is just as bad, and some stimulation is a vital component of tissue health and healing. This is the concept of “hormesis”: tissue is hurt by too little or too much action.

A sick tendon needs at least some moderate stimulation in order to move tissue fluids and to induce connective tissue repair. But what kind of stimulation, if you’re trying to avoid pulling it?

In the case of tendinitis, excessive pulling on the tendon is the most common cause of the problem in the first place. If this is the case, more pulling may be counter-productive. The friction massage technique is a way to stimulate the tissue in a new and different way. For whatever it’s worth, that’s the big idea: get the benefit of stimulating the tissue without any more longitudinal loading.

That’s a simple explanation for the usual rationale for this treatment. And I am not endorsing it — I’m just reporting it. That’s the conventional wisdom. What else might be going on?

What if tendinitis is about over-squished tendons, not over-pulled?

Not all tendinitis is necessarily about too much pulling (longitudinal forces). In some cases, the nature of overloading may be compression of the tendon as it is pinched against bone, like a bungie cord flattening when pulled taught around a corner.7 This probably occurs mostly where tendons attach to bones (insertional tendinitis) — for instance, right on the back of the heel where the Achilles tendon attaches, rather than the long skinny part higher up. In such cases, the tendon may be just as irritated by sitting/lying on it as by pulling.

If that’s so, does applying pressure make any sense? Maybe not! Frictions could be counter-productive.

On the other hand, a hypothetical partial compressive factor in some tendinopathy doesn’t seem like a deal-breaker to me. I doubt that frictions constitute the same kind of mechanical force as, for instance, lying or sitting on the afflicted tendon in gluteal or hamstring tendinopathy. A little brief gentle strumming ≠ sustained bodyweight compression!

Placebo?

Maybe the only way tendon friction is doing any good is by convincing people that it’s doing any good — a placebo. Manual therapy is a rich source of placebos, because hands-on attention is a great way to boost the perceived value of the treatment — and all the better if it’s a little uncomfortable. Slightly painful treatment must be “extra strength,” right?

I don’t know if frictions are just a placebo delivery trick, but it’s well worth bearing in mind.

Diffuse noxious inhibitory control?

To some degree you can temporarily treat pain by “distracting” the nervous system with a new pain. (Squirrel!) In short, pain can inhibit pain. Diffuse noxious inhibitory control (DNIC), AKA conditioned pain modulation, is a kind of “stupid human trick,” a fairly well understood neurological effect.8 Although it is not a placebo, it is a very common way to give a boost to a placebo in any no-pain-no-gain treatment. If a treatment hurts little, it can temporarily ease whatever pain you started with … which can strongly boost the belief that the treatment worked, and therefore also pump up the placebo.

So that’s going to be a factor in painful frictioning to at least some degree. Of course, frictions are not supposed to be painful! But not everyone agrees …

Breaking some eggs to make an omelette?

You could also describe (and do) frictioning more aggressively as a form of provocation therapy — hurting to help, breaking down to rebuild — and certainly some professionals perform it that way.

There are two “laws” of tissue adaptation, one each for hard and soft tissue: Wolff’s law covers bone, but Davis’ law for soft tissue — muscles, tendons, and ligaments, fascia — is relatively obscure and imprecise. Many treatments are based on the idea of forcing adaptation or “toughening up” tissues. It has always been a reasonable idea, but what’s the “right” amount and kind of stress? Results vary widely, but some of the most popular “provocation therapies” just don’t work, like scraping masssage and prolotherapy. More provocative provocation therapies include the injecting of an actual irritant (Prolotherapy, or “proliferative therapy”), or scraping with edged massage tools (for reals). See Tissue Provocation Therapies in Musculoskeletal Medicine.

Friction massage can certainly be done with the more dramatic intent of affecting the structure of the tendon, regardless of how painful the treatment is. While it is possible that this could work, it’s obviously riskier, and I don’t recommend it — and the next section offers an interesting reason.

Chronic tendinitis pain and neurology

The reductions in pain that occur at the time of applying the technique are easy enough to explain with “simple” neurology: almost anything that hurts will hurt less as you rub it and adapt to the stimulus. However, those pain-killing effects are also quite temporary. There is a way that neurology might actually account for a much more profound and lasting healing effect: by tinkering with sensitivity.

Chronic pain tends to be self-perpetuating. That is, pain can actually make you more sensitive to pain. In a lot of chronic pain cases, the problem is no longer in the tissue, but in nerves that have become oversensitive9 or a brain sounding false alarms.10

Friction massage may interrupt this vicious cycle, by systematically “teaching” the nervous system to be less concerned about stimuli of the irritated tendon. Virtually any stimulation has the potential to do this, but the standard protocol for friction massage might just be particularly good: precisely manageable doses of sensation, repeated over and over again.

(And excessively painful doses of sensation might very well just make things worse! This is why I don’t recommend that “deep” friction massage should be particularly deep. Stick to the Goldilocks zone and you’ve got a chance of working on the problem in two different ways.)

It’s only another theory, but quite a nice one. If true, virtually any stimulation might do the trick — all that would matter is repeated doses of mild to moderate intensity.

If tendons are all about pulling, why would they adapt to squishing?

One argument against frictioning is that tendons only “speak” in the longitudinal language of pulling, of tensile force, and if you don’t speak to them in that language, they are unlikely to adapt. Adaptation mostly occurs in response to functional loading: using the tissue the way that it is “meant” to be used.

A simple rebuttal is that nothing in the body is that simple and there are several examples of tissues that adapt to multiple kinds of stimulus, some of which aren’t common sensical at all. The mystery of bone loss in astronauts, despite vigorous exercise, is one of the best examples.11 It is really hard to know what actually constitutes “functional loading” for tissues.

So maybe pressure on tendons does constitute “functional loading,” because we know that the job description tendons is not limited to pulling on things.12

And another simple rebuttal is that loading doesn’t necessarily have to be functional to stimulate adaptations. In fact, it’s highly plausible that all tissues have at least some capacity to respond to virtually any stimulus, “functional” or otherwise. For instance, all tissues respond to acute stress and trauma with inflammation. The challenge to the tissue doesn’t have to be “functional” to get that … and indeed, we know that tendons do adapt positively to completely non-functional trauma!13

I doubt tendons only respond to tension, and the objection is fighting speculation with speculation. Tendons may not adapt to strumming, but we cannot know that a priori: it has to be tested, like anything else. Meanwhile, it’s plausible.

It’s about functional loading, stupid!

Many will argue that the only way to “fix” a tendon is graded functional loading, and that frictions are a silly distraction from that. But it’s not like “functional loading” is some kind of rehab slam dunk. Frictions may be experimental and speculative — as this article has always acknowledged — but so is functional load management to a significant degree.

No one can confidently optimize functional loading for recovery. Load tolerance is a function of tendinopathy staging, which is very hard to be sure of, plus unknown variables like sensitization, the impact of stress and exhaustion, genetic factors, and a long list of other potential medical vulnerabilities, many of them subtle. No one has the magic functional loading formula. We can never confidently tell a patient with tendinopathy, “Well, what you need is exactly this amount of longitudinal loading, at these times, and that tendon will adapt!” That would be wizardly.

But tendons can’t actually “heal,” so does that make frictions futile?

Like all connective tissue, a damaged tendon can never really get back to normal. They don’t heal, they just scar up. It’s kind of a “hack.” Tendons grow over lesions, adapting to trauma by generating a larger diameter, like putting new shingles down on a roof right over top of cruddy old ones. Maybe frictions can’t technically heal a tendon because tendons can’t truly heal at all — it’s just not in their nature.

And how do we know this? It has long been known that tendon tissue doesn’t have much turnover, but a fascinating 2013 experiment finally proved that it’s close to zero turnover, by showing that the atomic signatures of the era of nuclear bomb testing — I’m not kidding — are still written into the tendons of people who were alive at the time, trapped like bubbles of ancient air in an ice core.14 Incredible. Probably the coolest tendon study that has ever been or ever will be.

If a tendon has been degenerating for years, obviously our first choice would be to sprinkle magic tendon dust on it to restore its youthful perfection … but that option isn’t on the table. So what would we prefer: let it keep degenerating? Or have it lay down fresh, strong tissue over the rot?

There’s no guarantee frictions will stimulate that imperfect repair process. But the fact that tendon repair is imperfect is no reason not to try.

Is friction massage based on evidence?

Emphatically not — there is hardly any scientific research about friction massage at all, just a few slightly encouraging scraps.15 The absence of evidence is cause for concern — surely if the technique worked well it could have been proven by now? — but mostly it’s just a lack of research.16 The technique remains based mainly on speculation about the biology of rubbing. It simply “seems like a good idea” to some smart people. Regarding the conventional rationale, Hertling and Kessler write:

Although highly conjectural, the effects of friction massage are based on sound physiologic and pathologic concepts … . Until there is more concrete evidence of the value of friction massage, its use must be justified on the [basis of clinical evidence] combined with ‘educated empiricism.’

And that remains the case today, despite the important “paradigm shift away from an active inflammatory model since the popularization of the deep friction massage technique by Cyriax” (Joseph et al.).

The neurological perspective is my own take on it, which I’ve never seen anywhere else (but it is inspired by pioneers in pain research like Dr. Lorimer Moseley).

I often saw good results from the application of friction massage when I worked as a massage therapist, but that doesn’t really mean all that much. Many patients respond well to virtually any treatment — because virtually any kind of stimulation seems to have the potential to “reboot” a chronically painful situation in the body. In general, I prefer not to take credit for most of my “success stories.”

Are there any risks to friction massage?

Some minor ones. There are only health risks if you are a bit reckless with it.

If you ignore excessive pain, you might accidentally attempt to friction massage something that isn’t tendinitis, and perhaps something that’s more vulnerable than tendinitis. For instance, if you try to friction massage a bursitis, you are probably going to really regret it for a few hours!

However, pain is an excellent guide. As long as you don’t persist when friction massage is too painful or showing no signs of working, you’re extremely unlikely to cause any harm.

Otherwise, the worst-case scenario for self-treatment is that you’ll waste a few minutes of your time. This is actually fairly likely. Although friction massage does seem to help many cases of tendinitis, unfortunately there are many conditions that get mistaken for tendinitis, and will therefore not be helped by friction massage.

If you pay a professional to do friction massage to you, there’s also a risk of wasting your money. In principle, I think friction massage is too sketchy to justify paying for it. In practice, it’s probably not a time-consuming enough procedure to be of much concern (compared to many other much more expensive/recurring treatments). A brief paid experiment might be appropriate for some desperate patients who can readily afford it. But the aggregate cost, for all patients over time, for a treatment that is basically just an educated guess … that’s a little worrisome. Professionals should do the big picture math and ask themselves if they want to be selling shots in the dark.

Tendinitis-like conditions that may not respond as well to friction massage

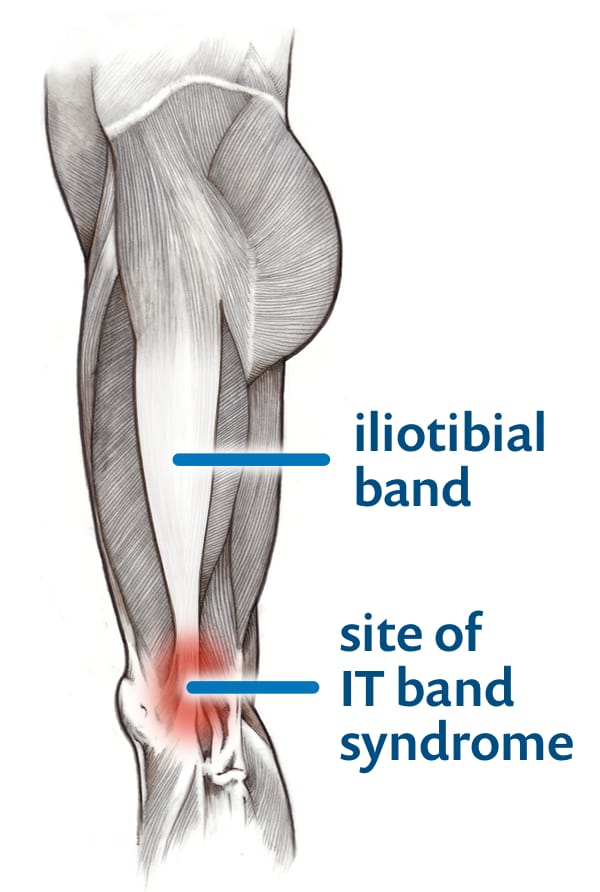

Iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS), a.k.a. runner’s knee, is a common condition causing strong pain on the lateral surface of the knee. And it is almost certainly not a tendinitis, per se. Recent scientific evidence has clearly shown that ITBS is much more likely to be caused by irritation of tissue underneath the tendon, and not by the tendon itself. Friction massage is less likely to provide the right kind of stimulation for this condition, and that’s what evidence shows.17

Iliotibial band syndrome is not a tendinitis, and probably cannot be helped by friction massage. In fact, ITBS is a greatly misunderstood condition in general. For more information, see PainScience.com’s advanced tutorial about IT band syndrome.

Tennis elbow may or may not be a “true” tendinitis, despite appearances. Myofascial pain syndrome (muscle knots) in the forearm is much more common than true tendinitis, and yet causes extremely similar symptoms. The main difference is a subtle difference in location and “hotness” and “sharpness” of the pain. Tendinitis will be a nastier, sharper, more burning pain with greater sensitivity to pressure—and felt primarily in the tendon. Myofascial pain syndrome will involve duller, more aching pain, with the greatest sensitivity just a little further “south” in the muscles. Since the two conditions routinely co-exist, aggravating each other, you’re unlikely to have a clear sense of the problem being one or the other. This also means that your mileage with friction massage will vary — it may work well, or it may not work at all.

Plantar fasciitis, a common kind of pain in the arch of the foot, is another complex condition that is sort of like a tendinitis, but not really. Certainly it involves irritation of the connective tissue on the bottom of the foot, which is sort of like a tendon. However, plantar fasciitis is often more complex, and friction massage is more of a hail Mary treatment here — and meanwhile, there are some more evidence-based treatment methods for it. However, feel free to try a little friction massage!

A little more about muscle knots

So-called “muscle knots” — AKA trigger points — are small unexplained sore spots in muscle tissue associated with stiffness and soreness. No one doubts that they are there, but they are unexplained and controversial. They can be surprisingly intense, cause pain in confusing patterns, and they grow like weeds around other painful problems and injuries, but most healthcare professionals know little about them, so misdiagnosis is epidemic.

Trigger points fairly routinely fool people into thinking that they have tendinitis. Don’t be fooled! Surprisingly intense muscle pain is a much more common phenomenon than tendinitis (and tendinitis isn’t exactly rare). At their worst, muscle knots can be extremely painful and seem very, very much like a tendinitis. However, most muscle knots can’t hold a candle to the hot, burning intensity and extreme sensitivity of a tendinitis.

A true, acute tendinitis has the sensitivity of an infected hang nail — you can barely brush it or move the muscle without jumping in pain. Muscle knots usually involve duller, more aching pain that rarely seems to be “in” a tendon.

Trigger points can often be treated easily by a wide variety of massage techniques. Ironically, sometimes friction massage might seem to be successfully treating a tendinitis, when in fact it might be successfully treating a muscle knot.

Muscle pain is incredibly common. That’s why I offer a popular basic self-massage guide, as well as an extremely detailed trigger point e-book for people with tougher cases …

Did you find this article useful? Interesting? Maybe notice how there’s not much content like this on the Internet? That’s because it’s crazy hard to make it pay. Please support (very) independent science journalism with a donation. See the donation page for more information & options.

About Paul Ingraham

I am a science writer in Vancouver, Canada. I was a Registered Massage Therapist for a decade and the assistant editor of ScienceBasedMedicine.org for several years. I’ve had many injuries as a runner and ultimate player, and I’ve been a chronic pain patient myself since 2015. Full bio. See you on Facebook or Twitter., or subscribe:

What’s new in this article?

2018 — Two new sections exploring theoretical arguments against frictions.

2017 — Three small new sections added to the discussion of how frictions allegedly work: compressive tendinopathy, placebo, and diffuse noxious inhibitory control. I also now clearly state that I have described the rationale for frictions, not endorsed it. Added a recommendation not to pay for frictions. There is a skeptical theme to today’s updates. 😉

2017 — Cited Chaves on the prevalence of friction massage and inconsistent technique; a few minor related edits.

2005 — Publication.

Notes

- Hertling D, Kessler R. Management of common musculoskeletal disorders. 3rd ed. Lippincott; 1996.

An excellent technical overview of friction massage for professionals.

- Chaves P, Simões D, Paço M, et al. Cyriax's deep friction massage application parameters: evidence from a cross-sectional study with physiotherapists. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2017 Sep;32:92–97. PubMed 28934644 ❐ This paper reports use of friction massage by almost 90% of 478 surveyed physical therapists. That’s really high.

- Which is true of nearly everything in the world of manual therapy (see papers like Cashin, or my explanation of the problem of “pseudo-quackery” in physical therapy). This isn’t an excuse — that’s just how it is. More on the scanty evidence below.

- When choosing treatments, please be wary of the 3 D’s: treatments that may be dangerous, dubious, and distracting (costly or time-consuming). No pain treatment is perfect, but does it at least make sense? Is it safe? Cheap? Reasonably convenient? Friction massage does quite well when considered in this way.

- Chaves 2017, op. cit. “Our results have shown that the application parameters are heterogeneous and diverse.”

- Khan KM, Cook JL, Taunton JE, Bonar F. Overuse tendinosis, not tendinitis, part 1: a new paradigm for a difficult clinical problem (part 1). Phys Sportsmed. 2000;28(5):38–48. PubMed 20086639 ❐ “Numerous investigators worldwide have shown that the pathology underlying these conditions is tendinosis or collagen degeneration.” For much more about this, see my Guide to Repetitive Strain Injuries.

- Cook J, Purdam C. Is compressive load a factor in the development of tendinopathy? Br J Sports Med. 2012 Mar;46(3):163–8. PubMed 22113234 ❐

From the paper’s conclusion: “Although the science is incomplete in substantiating a role for compression in the typical tendinopathies encountered in clinical practice, we have endeavoured to provide a cellular, biomechanical and clinical level for such a hypothesis to improve understanding and management of tendinopathy.”

- Diffuse noxious inhibitory control (DNIC), AKA conditioned pain modulation, is the temporary relief of pain caused by “distracting” the nervous system with some other discomfort, a fairly well understood neurological effect (Bars et al.). This is closely related to the phenomenon of counterstimulation (powered by gate control theory), in which non-painful stimuli weirdly “pre-empt” noxious stimuli. Although DNIC is not a placebo, it is probably an interesting way to boost a placebo in any no-pain-no-gain treatment. If a treatment hurts a bit, it can indeed temporarily ease whatever pain you started with … which can strongly reinforce the belief that the treatment worked, and therefore also pump up the placebo effect.

- Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: Implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain. 2010 Oct;152(2 Suppl):S2–15. PubMed 20961685 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 54851 ❐

Pain itself often modifies the way the central nervous system works, so that a patient actually becomes more sensitive and gets more pain with less provocation. That sensitization is called “central sensitization” because it involves changes in the central nervous system (CNS) in particular — the brain and the spinal cord. Victims are not only more sensitive to things that should hurt, but also to ordinary touch and pressure as well. Their pain also “echoes,” fading more slowly than in other people.

For a much more detailed summary of this paper, see Sensitization in Chronic Pain.

- Ingraham. Pain is Weird: Pain science reveals a volatile, misleading sensation that comes entirely from an overprotective brain, not our tissues. PainScience.com. 16515 words.

- Long after Wolff’s Law was formulated, about how bones adapt to physical stresses, it was still a perfect mystery what mechanism of Wolff’s Law was failing in astronauts. No matter how much exercise they subjected themselves to while in orbit, they still lost too much bone mass, a real problem. Everyone more or less assumed that bones “spoke the language” of impact, torque, and sheer, but ... no, not just those things. There’s something else. After much consternation, it was finally discovered by Fritton et al. in 2009 that bones specifically speak the language of gravity — by transducing the motion of fluid in microscopic channels in bone, “a flow-induced system of mechanotransduction.” That is how to tell a bone how dense it needs to be: not the simple functional loading of usage that everyone assumed, but simply being in a gravity well.

- As discussed above, tendons do have to tolerate some compression, which we suspect because insertional tendinopathy is a thing, and it’s a thing caused by compression. If tendons are subjected to compression systematically by normal function, then likely they can adapt to it to some degree as well. One would hope. And, if that’s the case, then clearly they do not speak only the “longitudinal language.” They may well also speak the “compression language,” and thus react to compressive forces as well as longitudinal ones.

- Cook JL, Purdam CR. Is tendon pathology a continuum? A pathology model to explain the clinical presentation of load-induced tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med. 2009 Jun;43(6):409–16. PubMed 18812414 ❐ Cook and Purdam state that injections stimulate “a healing response in the tendon” and even that “injection itself, regardless of the substances injected, has been shown to have a beneficial effect on tendon structure.”Stabbing is hardly a functional load. That’s not speaking the language of longitudinal loading! And yet the tendon adapts. Cool.

- Heinemeier KM, Schjerling P, Heinemeier J, Magnusson SP, Kjaer M. Lack of tissue renewal in human adult Achilles tendon is revealed by nuclear bomb (14)C. FASEB J. 2013 May;27(5):2074–9. PubMed 23401563 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 53171 ❐

- Joseph MF, Taft K, Moskwa M, Denegar CR. Deep friction massage to treat tendinopathy: a systematic review of a classic treatment in the face of a new paradigm of understanding. J Sport Rehabil. 2012 Nov;21(4):343–53. PubMed 23118075 ❐ Comments: This review of the “efficacy of deep friction massage (DFM) in the treatment of tendinopathy” concludes that there’s basically still no hard data, and “its isolated efficacy has not been established.”

- “Absence of evidence” instead of “evidence of absence.” There are many bogus treatments that have been studied intensely for decades, never yielding convincing positive results. This is not the case here. It’s just virtually ignored scientifically.

- Loew LM, Brosseau L, Tugwell P, et al. Deep transverse friction massage for treating lateral elbow or lateral knee tendinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;11:CD003528. PubMed 25380079 ❐