This woman is wasting about 85% of her time. Do you know why?

The Unstretchables

Eleven muscles you can’t actually stretch hard (but wish you could)

Anatomy has limits. An owl can rotate its head as much as 270° and you can’t, because of differences between owl spines and people spines. Although anatomy is amazingly variable (for some examples, see You Might Just Be Weird) it still works about the same for most people, and there are anatomical limits on all stretches … some more than others.

Tensile force can not be applied equally to all muscles. Most of us will hit the end of the natural range of motion of the joint long before we’ve stretched anywhere near as hard as you can stretch other muscles. In other words, some muscles are just biomechanically awkward to stretch. I call them “the unstretchables” — a bit of hyperbole, but true in spirit. Although these muscles can be elongated, they can’t be elongated enough to create the satisfying sensation of good stretch.

This is the most under-appreciated of many problems with the therapeutic value of stretching.1 If more people understood it, more people would realize that they are wasting their time with a variety of popular stretches.

Many muscles are stretchable, of course

One of the most “stretchable” of all muscle tissue in the body is the hamstrings muscle group on the back of the thigh: the biceps femoris, and the entertainingly named “semis,” semitendinosus and semimembranosus.

We are well-built for hamstring stretching. We have good leverage for it. Thanks to the arrangement of our parts, there is almost no limit to the amount of tensile force we can apply to the hamstrings — much more than the muscles can actually tolerate. If you could stand the pain, you could tear your hamstring muscles. You could literally rip them apart. Wow.

There are a few other muscles like this in the body.

But the opposite is true of several other muscle groups in the body. Just as anatomy facilitates strong tension on the hamstrings with convenient and powerful leverage — applicable simply by leaning forward — many muscles just do not allow full elongation and/or conveniently applicable and powerful leverage. There are several muscles that you can barely stretch at all, let alone tear, no matter how hard you try.

Biomechanical destiny — how normal anatomy can block a stretch

The most straightforward example of an un-stretchable muscle is the thick shin muscle. Yes, your shin has a muscle — the tibialis anterior, the meat in the meaty part of the shin.

The tibialis anterior muscle lifts the foot. It is elongated by pointing the toe like a ballerina, technically called “plantarflexion” of the talocrural (ankle) joint. However, the ankle joint only goes so far in that direction — its range of motion is strictly limited by the shape and arrangement of the ankle bones. There’s minimal variation in this limit from person to person — even a Cirque du Soleil contortionist can only plantarflex so far.2

Short of breaking your ankle, there is no way to plantarflex enough to stretch your tibialis anterior3 At maximum plantarflexion, the tibialis anterior muscle is not really “stretched” — it is mildly elongated. It is certainly longer than it is when it is contracted, but it is not being subjected to strong tensile force. It cannot be satisfyingly stretched!

And what a shame, too, because the tibialis anterior muscle could probably use a good stretching. It is often stiff and painful, because it harbours a classic trigger point4 — perfect spot for massage #3 — and it’s clinically significant in many cases of shin splints and plantar fasciitis, two of the most common and annoying musculoskeletal problems in the world.

Tough luck. You can’t stretch your tibialis anterior. It’s biomechanical destiny.

Good luck pulling on that! Ten more muscles you can stop trying to stretch

There are about 300 skeletal muscles in the human body. Sort of. It depends on how you count them. See How Many Muscles Are In the Human Body? A slightly tongue-in-cheek tally of our many muscles.

Many of them are “un” stretchable, but many of those don’t really matter much. Consider the humble coracobrachialis muscle — from a massage therapist’s perspective, it’s about as clinically ho hum as they come: a minor helper in shoulder flexion, overshadowed and overpowered by the famous biceps and the obscure but powerful brachialis muscles, the coracobrachialis is almost never clinically significant. Rarely injured in isolation, never even home to a troublemaking “trigger point,” the coracobrachialis is not just unstretchable … no one even cares to even try.

The Unstretchables — with a capital ‘U’ — are the ten muscles in the body that we can’t stretch to a satisfying degree but wish we could.

Masseter and temporalis

Why it’s unstretchable: The jaw can only open so far.

Why it’s a dang shame: Jaw tension is epidemic, and trigger points in these muscles cause a wide array of strange face and head pains, including toothaches, headaches, and earaches.

The suboccipitals

Why it’s unstretchable: Neck flexion is stopped by the chin hitting the chest, sharply limiting suboccipital stretch in most people. Although mildly stretchable in some people, it’s impossible for others, and an awkward and limited stretch for most.

Why it’s a dang shame: Suboccipital trigger points in this muscle group are a common cause of tension headaches.

Supraspinatus

Why it’s unstretchable: This muscle lifts the arm to the side. Going the other way is impossible: the torso is in the way!

Why it’s a dang shame: Supraspinatus, like all the infamous rotator cuff muscles, is prone to trigger point formation and injury. It’s also the site of common shoulder problems (supraspinatus tendinitis and/or supraspinatus impingement syndrome).

Pectoralis minor

Why it’s unstretchable: Can only be stretched by lifting the scapula, which is limited by many other tissues and lack of leverage — there’s just no way to apply the stretch. Standard pectoralis stretches primarily effect the pectoralis major.

Why it’s a dang shame: Routinely a cause of significant feelings of tightness and pain in the chest and arm, and it may also be a factor in thoracic outlet syndrome, which includes impinging the brachial artery and impairing circulation to the arm.

Thoracic paraspinals

Why it’s unstretchable: The thoracic spine is naturally flexed (thoracic kyphosis) and can’t flex much further due to the presence of ribs and sternum in front — i.e., you can only “hunch” your back and collapse your chest so far.

Why it’s a dang shame: The big spine muscles in the upper back may be the single most common location in the entire body for minor but exasperating muscular tension and aching.

Supinator

Why it’s unstretchable: This muscle rotates the forearm to turn the palm upward (supinating). Turning the other way (pronating) to stretch, the radius simply collides with the ulna.

Why it’s a dang shame: Although an obscure muscle, the supinator is nevertheless a key player in lots of wrist pain (often including carpal tunnel syndrome), tennis elbow, and golfer’s elbow.

Latissimus dorsi

Why it’s unstretchable: Too long and lanky to stretch — no matter how far you move the arm, tension on the latissimus dorsi remains fairly low.

Why it’s a dang shame: With its broad attachments in the low back, it would be nice to be able to try stretching this muscle strongly as a part of low back pain self-treatment.

The gluteals

Why it’s unstretchable: Stretching of the surprisingly long gluteus maximus muscle is blocked by the limits on hip flexion: the belly hits the thigh long before the muscle is truly stretched (especially if you’re overweight). The smaller gluteus medius and minimus, which lift the leg out to the side, can be stretched only awkwardly at best — the other leg gets in the way!

Why it’s a dang shame: All of the gluteals commonly contain trigger points that are clinically significant in most cases of low back pain, hip pain, sciatica, and leg pain. It would be wonderful to have the option of stretching them!

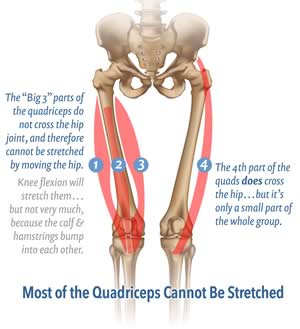

The quadriceps (seriously)

Why it’s unstretchable: The most surprising of the unstretchables, because everyone has done a quadriceps stretch, and you probably think you “know” that they can be stretched. However, you were only stretching the rectus femoris muscle — about 10–15% of the mass of the group. It feels like a strong stretch, and it is — of that tissue. But the other 85–90% remains only mildly elongated. The quadriceps consists of four muscles: the skinny rectus femoris and the three huge “vasti” — vastus lateralis/intermedius/medialis. The vasti are only elongated by knee flexion, which is limited to about 120˚ when the calf hits the hamstrings. The vasti cannot be stretched strongly.

Why it’s a dang shame: Even more surprising is that stretching most of the quadriceps strongly is not only impossible, but clinically unimportant. It would probably feel great to stretch them, but the state of the quadriceps is not a major factor in any common problem.

Tibialis anterior

Why it’s unstretchable: Limited ankle flexion.

Why it’s a dang shame: Stretching might be helpful for self-treatment of shin splints and plantar fasciitis.

The foot arch muscle

Why it’s unstretchable: The connective tissues in the arch of the foot are shorter than the muscles. When you stretch the arch, the first thing you feel is the plantar fascia reaching the limits of its elasticity. The arch muscles are also elongating, but not strongly.

Why it’s a dang shame: The arch gets tired and achy easily, and being able to stretch it more strongly would probably feel great — and possibly therapeutic for plantar fasciitis (or not, see Digiovanni).

The IT band

Why it’s unstretchable: Not a muscle, really. But the iliotibial band (actually sort of a giant tendon for the tiny tensor fasciae latae muscle) is one of the most stretched of all anatomical structures … and the most uselessly so. Supposedly IT band stretching is a treatment for IT band syndrome (runner’s knee). However, there is a perfect storm of unstretchability here: not only is the IT band unbelievably tough, but it cannot even slide or elongate because it is firmly attached to the thigh and femur, and when you try to stretch it you are mainly going to hit the limitations of the hip joint itself and the gluteus medius and minimus muscles (Willett et al.). Its immunity to stretch has been quite well studied (Falvey et al., Wilhelm et al.).

Why it’s a dang shame: If only you could actually stretch the IT band, perhaps it would be an effective treatment for a frustrating repetitive strain injury. This topic is analyzed in more detail in IT Band Stretching Does Not Work (free), and there’s even more detail in my IT band syndrome e-book (not free).

Some other examples of unstretchables, or only partially stretchables

I’ve chosen a dozen relatively obvious examples to feature, but there are a lot more possibilities, mostly more obscure. For these, I’ll mostly leave it as an exercise for the reader to think about why they are unstretchable, and just add a few minor miscellaneous comments. Hat tip to Mark O. for brainstorming some of these with me.

- Tibialis posterior — Much like tibialis anterior, but the clinical value of stretching this one seems less to me.

- Brachialis — The muscle under your biceps has only minor tension on it when the arm is straight, and that’s the end of the line. Even someone who can hyperextend their elbow is only going to go a few more degrees.

- Brachioradialis — Another elbow flexor and, as with brachialis, the elbow only extends so far.

- The serratus muscles — One of the most significant omissions from my main list.

- Deltoids — People rarely crave stretch here, and a good thing, because it’s nearly impossible.

- Intercostals — The intercostals are a bit ambiguous. For sure they can be stretched, but it’s equally clear that a strong stretch is out of the question.

- Transverse abdominis — It’s not a muscle ever think of stretching, but it’s truly unstretchable.

- Quadratus lumborum — Another strong candidate for the main list! This is one people want to stretch, try to stretch, and to some extent can stretch… but only so far, with only a floating rib as an anchor.

- Rhomboids — Half stretchable, perhaps?

- Popliteus — Probably not very clinically significant, but a great example of a truly unstretchable muscle.

- Most of the little muscles in the hands and feet — It would probably feel nice to stretch some of these, some of the time but good luck with that.

Some unstretchables are more unstretchable than other unstretchables

Some of these muscles can, sort of, be stretched. But all of them are limited to a moderate intensity stretch at best (e.g., the gluteals), in most people, most of the time, using reasonably accessible methods.

Inevitably, some smarty-pants kinesiologist or therapist will write to me to complain about this list, claiming that they know how to stretch those muscles, and just because I don’t know my stuff I shouldn’t be yada yada yada. (This kind of reaction seems to be par for the course with the subject of stretching, which inspires bizarre emotions and strange loyalties in people.)

So let me address that inevitable complaint about this list off right now and say, “Yes, but.” Yes, I’m sure there are miracle methods that can get a certain amount of stretch out of some of these muscles: but not much, and not easily.

If you have an urge to bitterly complain about my list, start by suppressing that impulse, and then consider the possibility that you are taking this way too seriously. 😃 To quibble over the individual muscles and stretches is to miss the point. Which is …

Citation needed?

A common criticism of this article over the years has been that I present no scientific evidence. While I’m loath to deflect a call for evidence, it’s appropriate in this case. Not everything needs to be studied.

Half the point here is that the unstretchables are a matter of logic and mechanics, empirical testing not required. No one has studied this, and no one ever will, any more than they are going to try to scientifically prove that showers are moistening or that we can’t rotate our heads 180˚ like an owl.

Although it’s overkill — this really shouldn’t be necessary to spell out — I’ll provide a more extreme and simple example to make the point: elbow flexion is limited to about 150˚. It’s impossible to go further because the forearm collides with the biceps. This is not a matter for scientific research. If you understand the anatomy, you know the answer: the lateral head of the triceps, which crosses only the elbow joint, cannot be strongly stretched, because the elbow can only flex so far.

You could prove it — there are ways of measuring the intensity of stretch on any muscle — but it would be rather silly to go to the trouble. Anyone who doubts this and insists on a citation is simply failing to understand the implications of basic anatomy. In this case, a citation is really not needed.

But, but, but … fascia can save the unstretchables, can’t it?

Not remotely. An increasingly common response to this article is to claim that the unstretchables are in fact stretchable via the rather arcane mechanism of “fascia” (sheets of connective tissue). Here are some typical examples (errors reproduced as received):

- “No muscle works in isolation.They are also fascially attached to the full length of the muscle to each other and the fascia extends further above and below joints. Further, there are many angle to stretch these muscles both assisted and self stretching methods. angles count in stretching. stop thinking just liner stretching start thinking spirals and diagonals.”

- “Hang on a minute, this assumes that the muscle is only connecting to the bone. I’m not one of those that just cries "fascia" at everything, but if we’re too anatomically reductionist we are going to miss the point.” Anatomically reductionist? As opposed to what, exactly? “Anatomy” literally comes from word roots that mean “to split apart”! Anatomy is reductionism (and that’s fine).

- “Of course, [Ingraham is] talking about purely stretching muscle tissue and not fascia which is a whole different approach.....”

These protests all share a conviction that you can somehow stretch a muscle even when you are not able to do so by moving its primary joint. This is easy enough to test. Either you can produce significant tension in a muscle without moving its primary joints or you cannot. Can you? Try it.

I certainly can’t. Nowhere in my body can I produce any noteworthy pull on any popularly stretched muscle without moving the joint it crosses. I cannot stretch my ass by extending my knee. Are the glutes and hamstrings fascially connected? Enough that I can somehow pull on my glutes just by playing with my knee position? Not even close.

Muscle stretch is consistently obvious in response to the straightforward biomechanical relationships. But absolutely no significant increases in tension are ever observable without elongating the obviously involved muscles.

Another example: the second reader comment above concerned the quadriceps specifically. It implied that the vasti have such substantial non-tendinous connections above the hip joint — not just above the vasti, but above the hip — that hip extension might actually result in a real pull on the vasti group. I don’t buy it. In fact, it’s pretty far out.

All of this speculation misses the point completely. It’s just more bizarre intellectual squirming to avoid the perfectly harmless conclusion that stretching isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. It’s also yet more unjustified aggrandization of fascia as a tissue (as if there wasn’t enough of that already). See Does Fascia Matter? A detailed critical analysis of the clinical relevance of fascia science and fascia properties.

Clinical implications of muscles you can’t stretch

The unstretchables are a problem for stretching. But what about the almost unstretchables?

For every more or less unstretchable muscle in the body, there are a half dozen more than are at best rather awkward to stretch. Thus, stretching as a self-treatment suffers from a major practical limitation, and can really only be used with the handful of major muscles/groups that just happen to be conveniently stretchable.

We don’t stretch what we need to stretch … we stretch what we can stretch. Which isn’t all that much. The neck and low back. The hamstrings and calves. The tiny rectus femoris part of the quadriceps. The abdominals and iliopsoas. The pectoralis major. Some of these are indeed pleasant to stretch and may have therapeutic value. But there are many important muscles left out …

If muscles cannot be stretched due to straightforward mechanical limitations, then they are simply immune to all of the rest of scientific controversy about stretching. If a lot of important muscles can’t be stretched, then there’s less value in debating the effects of stretching.

It’s just another thing that makes the stretching “debate” seem over-rated to me.

Social implications of muscles you can’t stretch

Er … social implications?

Now that you understand the concept of “unstretchable” muscles, I have cursed you with a heavy burden of secret and unpopular knowledge, and you are on an ideological collision course with devoted fans of biomechanically futile stretches. The subject of stretching tends to get people a little bent out of shape.

For instance, let’s say you’re a runner (and a great many of my readers are). From now on, you’ll never, ever be able to “stretch” your quadriceps alongside other runners without wanting to say something about it. But just try it. You’ll find out what I mean. It gets awkward and weird, fast. People do not like their stretches to be criticized.

I’m so sorry I’ve done this to you. Good luck out there.

Did you find this article useful? Interesting? Maybe notice how there’s not much content like this on the Internet? That’s because it’s crazy hard to make it pay. Please support (very) independent science journalism with a donation. See the donation page for more information & options.

About Paul Ingraham

I am a science writer in Vancouver, Canada. I was a Registered Massage Therapist for a decade and the assistant editor of ScienceBasedMedicine.org for several years. I’ve had many injuries as a runner and ultimate player, and I’ve been a chronic pain patient myself since 2015. Full bio. See you on Facebook or Twitter., or subscribe:

What’s new in this article?

2019 — Two new sections: “Citation needed?” and “Some other examples of unstretchables, or only partially stretchables.” Also implemented a huge improvement to readability on small screens. Feel more welcome, smartphone readers!

2018 — Significant revision of the introduction: the article now gets to the main point way faster, and a bunch of peripheral controversies about stretching are now left out, so they don’t freak readers out so much that they stop reading before getting to the main point. I have other articles for that.

2017 — Science update — added citations relevant to IT band stretching.

2008 — Publication.

Notes

Stretching is over-rated, which I explain in another article, Quite a Stretch. But in a nutshell: it doesn’t reduce injury rates (there are better ways), it doesn’t stop soreness after exercise (nothing does), and it isn’t a good “warm up” (there are much better ways to warm up, especially mobilizing). Not only is stretching much less effective at increasing flexibility than people think (it’s actually difficult and fairly dangerous), flexibility itself is also over-rated (being “inflexible” isn’t a problem for most people) and difficult (I never get more flexible, and God knows I’ve tried). Although stretching does feel good, and it can often take the edge off of muscle pain and stiffness … it rarely works any miracles or cures for muscle “knots.” Alas.

Considerable scientific controversy and mystery surrounds some of these points, but there are just too many reasonable doubts to ignore: the science of stretching tends to underwhelm anyone who looks into it.

- Bizarrely, I’ve seen some people actually disagree with that — stretching zealots so hell-bent on worshipping stretch that they do not believe that an ankle joint has limits. Incredible.

- Reminder: stretch is defined here as enough tensile force to produce a “satisfying” sensation of stretch.

“Myofascial trigger points” are a factor in most of the world’s aches and pains and the inspiration for most massage. The conventional wisdom defines them as tiny cramps, but there’s plenty of controversy about that. However they work, no one doubts that sensitive spots in muscle — like the one often found in the tibialis anterior — are common and linked to stubborn body pain. The pain often spreads in odd patterns, and trigger points grow like weeds around other painful problems and injuries, making them interesting and tricky.