How Many Muscles Are In the Human Body?

A slightly tongue-in-cheek tally of our many muscles

There are about 700 named skeletal muscles in the human body, including roughly 400 that no one cares about except specialists. There is just one important cardiac muscle. And there are literally countless smooth muscles (which do the work of the autonomic nervous system, mostly squeezing and squishing stuff in tubes).

But it depends on how you count. So how many muscles really?

It’s surprisingly hard to tell. You wouldn’t think the total number would be ambiguous, but it’s difficult to know what to include and exclude, and anatomists don’t always agree. Some muscle tissue really can’t be separated into countable muscles. And, believe it or not, the science of anatomy is still advancing. No, entirely new muscles aren’t being discovered — but novel variations in individual muscle anatomy are found more or less constantly,1 and supernumerary muscles — extra muscles — are not unusual.2 Many muscles, like the four-part quadriceps, are normally split into different parts that may or may not traditionally count as separate muscles3 — but then some people’s muscles are more divided than others. It makes a firm count just about impossible.

There are only about 200 to 300 muscles that anyone, even a massage therapist, might actually be interested in knowing about. When most people ask how many muscles are in the human body, they mean the serious bone-movers — muscles that do real work, muscles like pecs, delts, lats, traps, glutes, biceps and triceps, hams and quads … and let’s not forget the cloits and dloits.4 I never will.

There are maybe another hundred muscles if you include the fiddly little muscles of the hands and feet, and the major face muscles. In school, I had to learn the Latin for all them!

No, really, how many muscles are there?

All right, all right — if you really must know, there are just shy of 700 named skeletal muscles.5

But that’s including about 400 muscles that, mostly, no one cares about except specialists. I am aware of a few that have clinical importance to a massage therapist, but I’m mostly just barely aware of their existence — like the smaller facial muscles, like the mess of little muscles around and under the tongue and around the voice box, like the muscles around the eyeball, or the crazy trampoline of muscles on the pelvic floor.

But believe it or not, although that’s all of the muscles you can count, that’s still not all of the muscle — not even close.

There’s more? Oh hell yes

Muscles comes in three types:

- skeletal, which moves us

- cardiac, which moves our blood

- smooth, which moves our bowels … and a lot more

If we include smooth muscle in our census, the job becomes truly impossible. Smooth muscle is the muscle of organs, the muscle that does the work of the autonomic nervous system, squeezing and squishing stuff in tubes mostly, but also raising hairs, focusing eyes, raising hairs,6 and pushing out babies.7 Smooth muscle blends with other smooth muscle, and exists at every scale from microscopic. You have single cells of smooth muscle wrapped around all but the tiniest of blood vessels,8 and you have organs like your stomach that are wrapped completely in three thick layers of smooth muscle.

It’s impossible to say where one smooth muscle stops and the next begins. Perhaps that’s why they call it smooth.9

At the other counting extreme, of course there’s that singular cardiac muscle: a category of one. Unless you’re a Klingon or a Time Lord, you have only one cardiac muscle, but hopefully it’s a big one.

Doing the muscle math

This is how I calculate it. We have …

- ~100 muscles that might get discussed in a gym (and of course only 20% of those get 80% of the shop talk)

- ~200 more muscles that are more obscure, but any self-respecting massage therapist should still know about them (or at least memorized them in school 12 years ago)

- roughly 400 more muscles that are really danged obscure, but various specialists know about them, and a handful are of special interest

- several million hair-raising muscles

- several billion smooth muscles cells blended together

- exactly 1 heart muscle

So I’m going to go with a grand total of approximately 50,100,000,701 muscles, accurate to within 99%.

There’s even more? Sarcomeres are basically “micro muscles” … and there are many trillions of those

Muscles are basically made of microscopic muscles — the microscopic “sarcomeres,” bundles of protein that are the smallest functional unit of muscle tissue. They are not actually “muscles,” of courses, but they really are rather a lot like muscles — extremely tiny, molecular-scale muscles, much smaller than a muscle cell. Muscle cells are actually filled with sarcomeres! Lots of them. Truly vast numbers, a mostly unknowable number. Probably trillions, maybe even quadrillions. We are basically talking about molecules here. Big ones clumped together, but molecules.

And yet every single sarcomere is functionally a lot like an extremely tiny muscle: an elongated structure that can contract.

About Paul Ingraham

I am a science writer in Vancouver, Canada. I was a Registered Massage Therapist for a decade and the assistant editor of ScienceBasedMedicine.org for several years. I’ve had many injuries as a runner and ultimate player, and I’ve been a chronic pain patient myself since 2015. Full bio. See you on Facebook or Twitter., or subscribe:

Related Reading

This article is part of the Biological Literacy series — fun explorations of how the human body works, what I think of as “owner’s manual stuff.” Here are ten of the most popular articles on this theme:

- Micro Muscles and the Dance of the Sarcomeres — A mental picture of muscle knot physiology helps to explain four familiar features of muscle pain

- The Unstretchables — Eleven muscles you can’t actually stretch hard (but wish you could)

- When To Worry About Shortness of Breath … and When Not To — Three minor causes of a scary symptom that might be treatable

- Why Do We Get Sick? — The curious and tangled connections between pain, poor health, and the lives we lead

- Does Fascia Matter? — A detailed critical analysis of the clinical relevance of fascia science and fascia properties

- Organ Health Does Not Depend on Spinal Nerves! — One of the key selling points for chiropractic care is the anatomically impossible premise that your spinal nerve roots are important to your general health

- The Respiration Connection — How dysfunctional breathing might be a root cause of a variety of common upper body pain problems and injuries

- You Might Just Be Weird — The clinical significance of normal — and not so normal — anatomical variations

- A Painful Biological Glitch that Causes Pointless Inflammation — How an evolutionary wrong turn led to a biological glitch that condemned the animal kingdom — you included — to much louder, longer pain

- Tissue Provocation Therapies in Musculoskeletal Medicine — Can healing be forced? The theme of hormesis in pain and injury medicine

- Toxins, Schmoxins! — The idea of “toxins” is used to scare people into buying snake oil

What’s new in this article?

2023 — Small new section, “There’s even more? Sarcomeres are basically ‘micro muscles’ … and there are many trillions of those.”

2023 — Corrected a minor error: capillaries are not muscular. Hat tip to reader M.C. for reminding me of that.

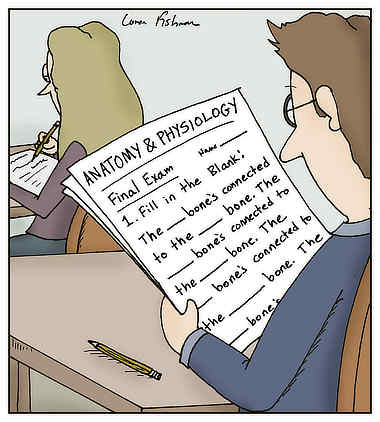

2017 — Added a cartoon.

2017 — Added a “fun fact” about the pupillary muscles.

2016 — Substantial miscellaneous improvements. Added a couple notable citations about anatomical variations. New featured image.

2004 — Publication.

Notes

- Natsis K, Totlis T, Konstantinidis GA, et al. Anatomical variations between the sciatic nerve and the piriformis muscle: a contribution to surgical anatomy in piriformis syndrome. Surg Radiol Anat. 2014 Apr;36(3):273–80. PubMed 23900507 ❐

This dissection study of 275 dead buttocks found that 6.4% of them had variations of sciatic nerve and piriformis muscle anatomy, with considerable variety in the variation. They found several different arrangements, and concluded: “Some rare, unclassified variations of the sciatic nerve should be expected during surgical intervention of the region.” Prepare to be surprised, surgeons!

All of these differences are potentially clinically significant, probably especially in the cases where the nerve (or part of it) passes right through the muscle. For a couple case studies, see Arooj 2014 and Kraus 2015.

- Hislop M, Tierney P. Anatomical variations within the deep posterior compartment of the leg and important clinical consequences. Journal of Science & Medicine in Sport. 2004;7:392–399. “ … anatomical variations may be present, such as supernumerary muscles, thickened fascial bands or variant courses of nerves and blood vessels, which can themselves manifest as acute or chronic conditions that lead to significant morbidity or limitation of activity.”

The quadriceps is always counted as 4 separate muscles (vastus medialis, vastus intermedius, vastus lateralis, and rectus femories). But the biceps and triceps muscles are also clearly bifurcated into distinct heads, and yet are not count as seperate muscles. Why? Maybe just to keep things interesting for anatomy students! Let’s ride this digression a little further…

Biceps, triceps, and quadriceps are all singular terms in Latin, but look like plurals to English speakers, and also seem plausibly plural because they all have substantial subdivisions. But there is no such thing as one quadricep, one bicep, or one tricep.

- There are no such thing as cloits or dloits, of course. This is a reference to anatomy according to Strong Bad, which is hilarious, and included here entirely for the sake of comic relief. Kind of like the whole article, come to think of it. I beg the indulgence of the creators of Strong Bad for using his likeness without permission — a copyright infringment for sure, but I have this (probably delusional) idea that they would perceive it as charming (rather than illegal) that I love Strong Bad so much that I would spread the word about him via an anatomy article.

- Tortora GJ, Grabowski SR. Principles of anatomy and physiology. 8th ed. Harper Collins College Publishers; 1996.

- The muscles that wave our body hairs around are a good example of the impossibility of counting smooth muscle. They are a sub-type of smooth muscle: not exactly like all the other smooth muscle, and yet not like miniature versions of your traps and pecs either. There’s several million of these little micro muscles, but, fortunately, they all have the same name: “Hi, my name is arrector pilli” x 7,000,000.

- Which is, technically, “squeezing and squishing stuff in a tube,” now that I think about it. A very specialized tube, but most of our tubes are. In men, smooth muscle also handles ejaculation.

- Blood vessels are wrapped in smooth muscle down to about 50 micrometres, 5% of a millimetre, which happens to fit the cliché of being about as thick of a human hair. Below that size, the smallest arterioles, venules, and capillaries (5–10μm) lack smooth muscle. (Hat tip to reader M.C. for reminding me that capillaries are too small to have muscles.)

![Electron microscope image of a capillary in cross-section, with a red blood cell in it. The capillary is a few micrometres wide.]()

Electron microscope image of a capillary in cross-section, with a red blood cell in it. The capillary is a few micrometres wide.

- Actually, they call it that because it’s non-striated, and so it looks smooth in a microscope compared to skeletal muscle, which is distinctively striped (striated) due to a much more regular arrangement of sarcomeres. Sarcomeres, by the way, are really cool.