How to Treat Sciatic Nerve Pain

A user-friendly, evidence-based guide for patients about how to manage buttock and leg pain (which may or may not actually involve the sciatic nerve)

If you mainly have low back pain, and not so much leg pain, please change articles: you should be reading the The Complete Guide to Low Back Pain

Sciatica is the informal term for one type of lumbar radiculopathy: pain and other symptoms caused by irritation of a lumbar nerve root (or a major branch of it). There may be some back pain too.

But these symptoms do not necessarily mean you have a cranky nerve root. “Pain below the knee” is the closest thing to a signature symptom, but not every patient with sciatica has that symptom, and some with that symptom do not have sciatica.1 The same is true for all the classic so-called sciatica symptoms: they just don’t tell the whole story.

There are several other possible causes of buttock and leg pain. For instance, irritation of the sciatic nerve can do it too. Technically that’s a peripheral neuropathy, but these two problems so similar in spirit — a huge nerve trunk in trouble instead of a nerve root — that both of them fit comfortably under the “sciatica” umbrella.

There are several different ways for the lumbar roots and sciatic nerve to get into trouble. Even when they seem to be in trouble, they may not actually be the cause. And then there are other causes of exactly the same symptoms! Is it still “sciatica” if it has nothing to do with nerve roots or sciatic nerves? Or should we use the word “sciatica” to refer to all buttock and leg pain and consider the specific cause separately, whether nerves are involved or not? There’s no official answer to these questions!

Many causes of buttock, hip, and leg pain

I'll go into more detail on selected possibilities, but here's a simple list of all the major ways that sciatica and similar pain might happen:

- Lumbosacral referral: Pain originating from the lower back and pelvis, often felt in nearby areas like the hips or thighs.

- Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: Narrowing of the lower spine, often resulting in back and leg pain or difficulty walking.

- Lumbar Radiculopathy: Irritation of nerves in the lower spine, causing pain, numbness, or weakness in the legs.

- Hip Osteoarthritis: Wear-and-tear damage to the hip joint causing stiffness, pain, and reduced mobility.

- Greater trochanteric pain syndrome: Irritation of the gluteal tendons that converge on the side of the hip, causing hip pain and tenderness on the outer thigh.

- Deep Gluteal Syndrome: Compression of nerves in the deep buttock area, causing pain or numbness in the hip or leg. Piriformis syndrome is the major example, but it’s probably not alone.

- FAI Syndrome: Impingement at the edge of the hip joint socket due to abnormal bone shape, leading to pain and limited movement.

- Mononeuropathies: Damage to a single nerve, typically causing weakness, pain, or numbness in the affected area. Can be a big nerve, like the sciatic itself, but there are several others that can seem similar.

- Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy: Progressive compression of the spinal cord in the neck, leading to pain, stiffness, and sometimes neurological issues … yes, even in the lower body.

Now, more detail about some things of particular interest …

- Intervertebral disc herniation looms large in our collective imagination, and it probably is the most common cause of sciatica — 85% of cases2 — but also probably not quite as much to blame as we fear, and certainly not as simple. Although it’s mostly about applying pressure to the roots of the sciatic nerve in the low back, there is obviously more to it, because disk herniations are asymptomatic surprisingly often. Pressure alone doesn’t do the trick — it probably has to be combined with inflammation, which is in turn affected by many other aspects of our health.3

- A common non-neurological cause of sciatica-ish pain is probably muscle knots or trigger points. When flared up, these mysteriously sensitive patches of soft tissue in the low back and gluteal musculature can cause symptoms that can spread down the back of the leg. Much more on trigger points below.

- Also allegedly common is impingement of the sciatic nerve by the piriformis muscle deep in the buttock, the elusive “piriformis syndrome,” which is as unproven as Bigfoot, but with a lot more credible “sightings.”6 A piriformis muscle contracted enough to cause this problem invariably contains trigger points that also radiate pain down the back of the leg, and so the two problems often overlap. It can be difficult to tell the difference between symptoms of the nerve pinch, and symptoms of piriformis and other muscular trigger points.

- In an unlucky few, the sciatic nerve, or part of it, actually passes through the piriformis muscle, rather than underneath it — one of the most problematic common anatomical variations.7 This probably results in a much greater vulnerability to sciatic nerve irritation — a kind of “super piriformis syndrome,” like piriformis syndrome with a hair trigger. In this case, sciatic nerve impingement is usually a more significant factor, and harder to resolve.

- Hamstring syndrome, in which fibrotic bands (from trauma, or born-with-’em) can trap and irritate the sciatic nerve where the hammies attach to the sit bones.8

- Cluneal nerve entrapment is not especially common, but has significant potential to act like sciatica — different nerves, similar results. The cluneal nerves pass from the low back and sacrum into the buttocks, just under the skin, and they can get tangled up with ligaments and connective tissue on their way, potentially causing chronic low back, buttock, hip, and leg pain.9 Although potentially similar to sciatica, this pain is likely to be higher, milder, achier, and affecting the hip and side of the thigh more than butt and hamstrings. Notably, this pain may also be hard to distinguish from common trigger points in the glutes. It’s also a major suspect in cases of …

- Greater trochanteric pain syndrome is a pattern of pain with an epicentre around the large bump of bone on the side of the hip. While it is usually experienced as hip pain, it routinely involves widespread pain in the low back, throughout the glutes, and down the side and back of the leg as well. It is a distinct condition in its own right, and yet it probably has more than one overlapping cause, including most of the things listed here (but especially cluneal nerve entrapment). Mild sciatica could even contribute to it, and be overshadowed by it — or vice versa. GTPS is often mistaken for IT band syndrome, probably mainly because the pain spreads down into the thigh where the big IT band tendon happens to be.

Most of these scenarios involves trigger points as either a cause or a complication. Trying to treat them is often a good way to intervene — to break the grip that piriformis has on the sciatic nerve, perhaps, or to improve the soft tissue environment of unhappy lumbar nerve roots. By no means is it guaranteed to work, but it’s quite easy, inexpensive, and safe to make the attempt.

Rarely is the problem “mechanical” in nature, despite the popularity of this view among virtually all health care professionals. Chiropractors are particularly prone to diagnose a sciatica problem as a symptom of some kind of joint dysfunction, alignment, or postural problem. The sacroiliac joint is often diagnosed as being “out,” and the lumbar joints are portrayed as being fragile and vulnerable when quite the opposite is true. Although chiropractors are most likely to diagnose in this way, physicians, physiotherapists and massage therapists are all equally prone to this kind of “structural” diagnosis … missing the most straightforward explanation and treatment opportunity.

A trigger point success story

Reader Alex B. send me a good anecdote about his rapid recovery from sciatica by treating muscles “knots” in his low back and upper gluteals:

Recently, seemingly overnight, I developed what appeared to be femoral neuropathy caused by a benign tumour (neurofibromatosis). I seemed to have some regular "sciatica" too. I spent months getting MRIs, going to chiropractors and physical therapists, with no relief. A surgeon told me to just accept that the tumour was the cause of the pain, but I didn’t believe him: a giant neurofibroma could surely cause pain, but I figured it would have been a slow build rather than overnight.

Anyway, I finally found your website. Sure as shit, I did the perfect spot #12 and #13 for one night — just a single dose — and I was 95% healed. It’s been 8 months since I could walk without a limp and I swear to god I am able to sprint again. I was doing flips into a pool this weekend!

I followed up with Alex a couple weeks later and confirmed that he was still doing well. Anecdotes are not evidence, of course, but stories like this are quite common in my experience.

Disc herniations are less of a problem than most people fear

The intervertebral discs are little pucks of tough, fibrous material between vertebrae. Disc herniations — often misleadingly called “slipped” discs — are strongly associated with sciatica. When a disc herniates enough, it may irritate nerve roots emerging from the spine, and be the main cause of sciatica.

But do not fear disc herniations! No matter how bad it looks on a CT scan or MRI, it is not necessarily the cause of the problem. Herniations correlate rather loosely with actual pain. They may be a distracting sideshow that unnecessarily worries people.

As mentioned above, just impinging a nerve is not, in itself, enough to cause sciatica — the real issue may be the nerve root’s vulnerability to getting inflamed by the physical irritation (Stafford et al.), which is affected by many other variables. This is a common theme in musculoskeletal medicine: loading or trauma that causes a lot of trouble for one person may have little or no effect on another.10 The good news is that, in principle, this means that there’s genuine potential for improvement regardless of the state of the disc herniation.

Another reassurance: “slipped” discs usually un-slip. This is called “resorption” — a nifty back trick that most people are unaware of (including too many healthcare professionals still). Most herniations, roughly 60%, just go away, like a snail tucking back into its shell, according to about a dozen studies.11

And of course a disc does necessarily not have to fully de-herniate to resolve sciatica.

How can I tell what flavour of sciatica I have?

You probably can’t. The symptoms just have too many possible causes. Even when the symptoms seem “obviously” neurological, they routinely aren’t. It’s just not possible to identify nerve trouble by the symptoms.

Patient descriptions like “pain below the knee,” “radiating pain in the legs,” “pain running down the leg,” have always been considered good indicators of a nerve root in trouble (radiculopathy). But do they really indicate that reliably? They do not! In a 2012 study of more than 500 patients with pain radiating to the legs, no single symptom, or cluster of symptoms, was clearly linked to actual nerve root pathology.12 Careful histories and exams were done on all of these people to find the true radiculopathy cases, and they just didn’t line up with the symptoms. The closest match was just:

- pain below the knee

But even that was still misleading: not every patient with sciatica has that symptom, and some with that symptom did not have radiculopathy. A cluster of descriptions also correctly identified quite a few cases, but still misclassified too many. This was the best batch:

- pain below the knee

- leg pain worse than back pain

- numbness or pins and needles in the leg

The profound subtext here is that symptoms are surprisingly uninformative. The nervous system is noisy and messy. The human body is a symptom-generating machine. We tend to think that problems cause more or less the same symptoms in everyone, but they just don’t. Some symptoms are “pathognomonic” — highly specific to a problem, unlikely to occur without that problem — but most aren’t.

Some kinds of symptoms do suggest neuropathy more strongly:

- true tactile numbness, in which you would not feel a light scratch

- pins and needles (called “parasthesia”)

- “lancinating” pain: hot, sharp, or electrical, instead of diffuse and aching

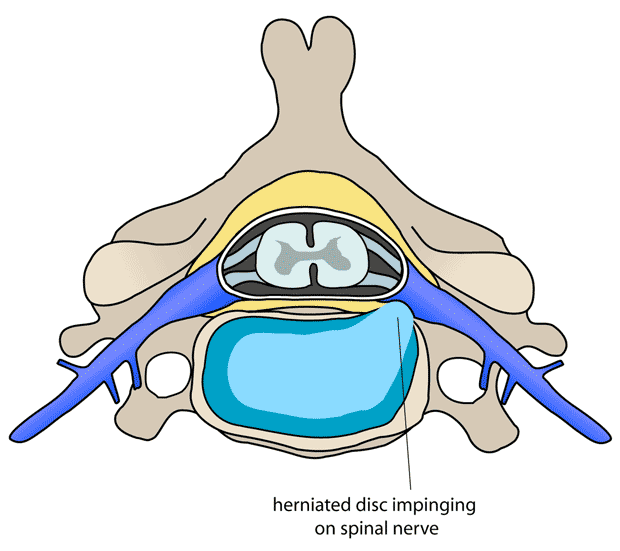

A disk herniation

Only one possible source of sciatic. This is cervical vertebra, but the principle is the same: the disc bulges outwards and presses on a bundle nerves. Illustration by “debivort,” Creative Commons License

Trigger points rarely causes a “pins and needles” sensation, so if you have pins and needles, I would bet on a neuropathic origin, not muscle pain. But you can’t be sure, because trigger points do occasionally cause a surprisingly nervy tingling.

The only symptom that is almost guaranteed to be caused by nerve impingement alone is also quite rare: true tactile numbness. If you have a “dead” patch of skin, then you almost certainly really do have a pinched nerve. But some uncertainty remains even then. Although trigger points cannot cause a truly numb patch of skin, they can (and routinely do) cause an intense feeling of “dead heaviness.” People routinely report numbness, but after a little discussion, it becomes clear that they mean that the leg feels sick, heavy, weak and useless … but not actually numb to the touch. Without numbness to touch, nerve impingement cannot be diagnosed, and by far the more likely cause of the symptoms are a batch of nasty trigger points in the low back and hips.

This difference between nerve impingement and trigger points can be extremely difficult for patients to wrap their heads around, so I’ll go into more detail in the next section. But first, a delightful patient quote of the day from Dr. Grumpy:

“The pain went down through my legs. Not all my legs, I mean, but just the ones on the bottom of my body.”

And if you think that’s weird, you should see my inbox.13

The fear of nerves

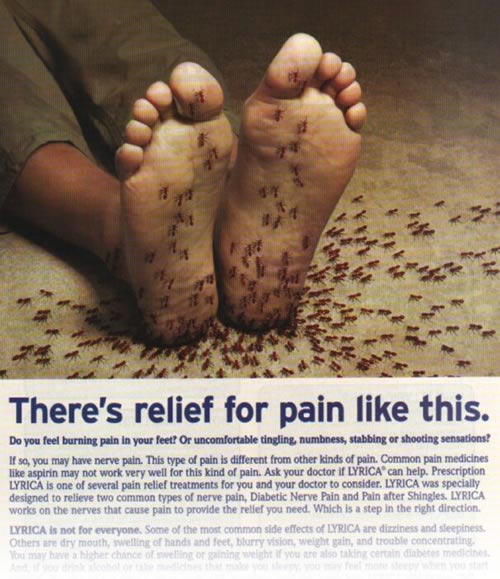

I came across this full-page advertisement in National Geographic magazine:

“Do you feel burning pain in your feet?” the ad asks. “Or uncomfortable tingling, numbness, stabbing, or shooting sensations? If so, you may have nerve pain.”

Yes, you might. But it’s not bloody likely! The clinical reality is that neuropathy is a lot less common than nearly all patients and most doctors believe.

Nerves have a mystique

Nerves make people nervous! So to speak. The whole idea of nerves gets people anxious. Could it be a nerve? people ask. Is this a nerve problem? What if it’s a nerve? Is something pinching my nerve? Something must be pinching a nerve.

The kind of advertisement with the stinging ants you see above greatly aggravates our society’s general anxiety about nerves. Pfizer and other pharmaceutical companies spend about a gazillion dollars on marketing that can create more worry about nerve pain in a year than I can counteract in an entire lifetime of low-budget public education! Bummer.

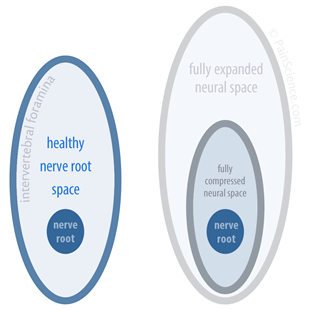

Nerve root wiggle room

It’s amazingly difficult to actually pinch most nerves, or nerve roots (as they exit the spine). In general, nerves have extremely generous “wiggle room.” For instance, in the lumbar spine, the holes between the vertebrae that the nerve roots pass through can be more than a couple centimetres at their widest, while the nerve roots themselves are only about 3-4mm thick.14 If you stretch or compress the spine, the holes do change size a little — as much as 70–130% in the looser neck joints,15 a little less in the low back.16 But even at their smallest, there’s still plenty of room.

Schematic of nerve root wiggle room

On the left are the approximate proportions of a healthy nerve root and the hole it passes through (intervertebral foramen). When the spine is pulled or compressed, the holes get a little larger or smaller, as shown on the right … but there’s still lots of nerve root room.

There’s so much space for nerve roots that even dislocations routinely fail to cause impingement.17 Once again, I invoke the example of a patient with a severe lumbar dislocation … and no symptoms at all, not even symptoms of pinched nerve roots. Her nerves seemed to be fine, even in an anatomical situation most people would assume to be extremely dangerous.

A young woman with “sciatica” (hint: not actually sciatica)

I worked with a young woman who had “sciatica.” Allegedly, her sciatic nerve was pinched by her piriformis muscle — a reasonably common scenario — and sending hot zaps of pain down her leg. She came to me with this diagnosis already in place. She also had some tingling in her feet. The description of her symptoms did, indeed, sound a lot like a nerve impingement problem. On the face of it, it did seem likely that her sciatic nerve was being pinched.

However, a couple things didn’t add up. For instance, she had no numbness at all — no dead patches of skin, which are highly characteristic of true nerve impingement. Instead, she had a lot of “dead heaviness” in the leg, a different kind of numb feeling that is much more closely associated with muscle knots than nerve pinches — and a lot more common.

I quizzed her carefully about the quality of her pain. She assured me it was “zappy” and “electrical” … just as you would expect of nerve pain. Yet something didn’t seem quite right. I couldn’t shake the impression that she was interpreting an intense non-neurological pain as a “zappy” pain simply due to her strong belief that she had a nerve problem. When you think a pain is nervy, you’re going to interpret, feel and describe it in nervy terms.

So I did some experimenting, and clinched the case:

This young woman’s “nerve” pain could be perfectly reproduced by prodding muscle tissue that was nowhere close to the sciatic nerve. Pressing on the side of her hip, on the gluteus medius muscle, several centimetres away from the sciatic nerve, she reported the same “electrical” pain flowing down her leg. It even stimulated the weird, tingling sensations in her foot.

This largely eliminates a diagnosis of sciatic nerve impingement.

A more likely story

In spite of spending most of my career trying to explain to people that this sort of thing is common, I was surprised myself — fooled, really. Muscle knots are always fooling patients and professionals alike. Vastly more common than nerve problems, and often more painful, they nevertheless get upstaged and misdiagnosed by another phenomenon.

Do you feel burning pain in your feet? Or uncomfortable tingling, numbness, stabbing, or shooting sensations? If so, you are more likely to have “muscle knots” than nerve pain.

The take-home message of this section is: do not underestimate the power of trigger points to cause pain that seems like a nerve pinch.

What’s the worst-case scenario for sciatica?

Most cases of sciatica will resolve on their own, with no special treatment, within 3–6 weeks, just like low back pain or a crick in the neck. Most people will never have the problem again, or only once or twice more in their lives.

The worst cases are completely debilitating for brief periods, but most of the time cause only extremely annoying pain that makes daily activities frustrating, but not actually impossible.

Unfortunately, a minority — perhaps 20% of patients — will become chronic and/or recurrent sufferers.18 An even smaller, unluckier minority of sciatica sufferers face a lifetime of pain that never or rarely leaves, or episodic pain that inevitably returns. Stubborn cases may be at least partially explained by genetics,19 and this one of the important reasons why patients need to be wary of therapeutic wild goose chases looking for the cause of their pain.

Once any kind of pain has been around for a while, it has the potential to actually damage the way the nervous system interprets pain — this is known as “sensitization,” meaning the nervous system has become oversensitive to pain.20

What can I do?

The next several sections go over some of the treatment options for sciatica. In summary, most people should avoid surgery, as it simply does not provide that much benefit. However, it may be a worthwhile option for very painful cases of sciatica. For everyone else, the best therapy is to try to “act normal” as much as possible — reduce fear and anxiety, move as much as reasonably possible, stretch and wiggle, keep the surrounding muscles happy with heat, and so on.

Surgery for sciatica (microdiscectomy)

Surgery for sciatica is only an option when it is caused by a herniated disc, as opposed to when the sciatic nerve is being impinged by the piriformis muscle, or (obviously) if sciatica-like symptoms are being generated by muscle knots alone (or something else altogether).

Even when there is a herniated disc, surgery should be seriously considered only in the most painful and persistent cases. As with most orthopedic surgeries, as of 2017, most of the evidence is poor quality and discouraging and what shreds of good news there are cannot really be trusted.21 There’s barely any difference between people who get surgery versus people who just focus on basic activity-based rehab. I’ll go over some specific research examples below.

Bear in mind that herniated discs are not necessarily painful. Even if they have made an appearance on an MRI, that does not necessarily mean that they are related to your problem. Or it might be. The idea of microdeskectomy is to cut away the disc that might be irritating the spinal nerve roots that the sciatic nerve comes from.

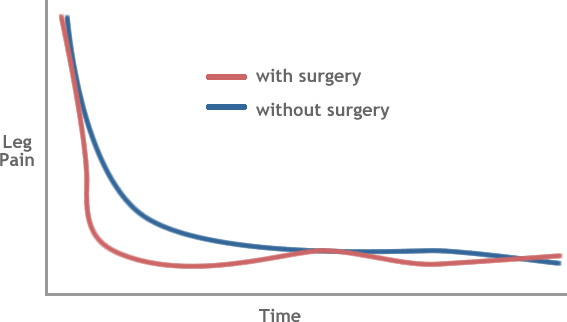

In 2008, a group of Dutch researchers published the results of a good study of surgery for sciatica.22 Although not perfect, it is one of the best such experiments available, and will be more or less the “last word” on the subject for a while, the new-and-improved conventional wisdom. This remains the case as of 2017. (It is also quite readable for a scientific paper, and keen patients or professional readers might want to browse the full paper, which is freely available.)

Peul et al. found that operating relatively quickly — not long after diagnosis — “roughly doubled the speed of recovery from sciatica compared with prolonged conservative care.” However, that sounds a lot better than it actually was: the speedy recovery didn’t last for long. In fact, “These relative benefits of surgery, however, were no longer significant by six months’ follow-up, and, even at eight weeks, the statistically significant difference between treatment groups in primary outcome scores was not sufficient to be clinically meaningful.” In other words, the effect of early surgery was quite underwhelming. A graph shows this very clearly:

That pretty much says it all, doesn’t it? For your trouble of getting cut open, you get a modest dip in pain in the early days, but soon after, you’re back in the same boat as the fellow who didn’t bother. “Neither treatment is clearly preferable,” the researchers concluded. They argued that it might be time to stop recommending surgery based on physician preferences, and start asking patients what they think of the options.

This study is less positive than some previous ones have been. However, it was a more carefully controlled test, and gives us many reasons to put more stock in its results. In fact, the results are so conclusive that authors wonder “whether surgery has any effect at all on the natural course of sciatica.”

I have been arguing for years that back surgeries need to be compared to sham surgeries if we are ever to truly know if they work, so I was particularly pleased that these scientists suggest exactly that. There are major challenges with comparing real surgeries to sham surgeries, but it can and has been done, with fascinating and routinely disappointing results.23

Slightly faster recovery and relief of leg pain might be worthwhile for some patients. However, much of this eagerness (and probably some of the pain) is driven by fear — back pain and sciatica have a unique ability to scare the pants off patients.

The risks of microdiscectomy are low as surgeries go, but there is still a considerable financial, personal, and social “overhead” any time people get cut open. We should avoid any kind of invasive medical procedure unless the benefits are extremely clear. Like a charge of murder, it should probably be proven “beyond a reasonable doubt” that surgery is worthwhile. Such proof is simply not present in this case of surgery for sciatica!

So, if you’re not going to get operated on … what else can you do?

Relax the area with heat and vibration

Whether the pain is caused by the crushed sciatic nerve itself, or just by tight muscles, the muscles need to relax in either case. Hot tubs, with jets, are ideal for most sciatica cases.

Due to the thickness of the tissue in the buttocks, the heat will not have any circulatory effect on the nerve or the piriformis muscle, but it will be neurologically sedative. The vibration of jets will amplify that effect. Muscles relax when they are vibrated — a neurological effect known as “proprioceptive confusion.”

(If you live in Vancouver, see the footnote for a great local tip.24)

To get the most out of using any hot tub, see Hot Baths for Injury & Pain.

Apply a tennis ball

The muscles of the hip and buttock are one of the few places in the body where it is possible to effectively treat your own muscle knots with a tennis ball. Simply lie on a tennis ball such that it presses on deep, aching sore points — and wait for the sensation to fade. See Tennis Ball Massage for Myofascial Trigger Points for more information. I do have one caution about treating yourself in this particular case: the piriformis muscle is so unusually reactive, in my experience, that you must be particularly gentle and conservative in your approach.

No bed rest — it doesn’t work! Simple exercise and activity instead

Bed rest has been a popular treatment for sciatica for the better part of the last century. It’s more or less dying — most doctors know that it doesn’t work these days, and don’t prescribe it. But you still run across this myth from time to time.

In a 1999 sciatica study in New England Journal of Medicine,25 researchers “randomly assigned 183 subjects to either bed rest or watchful waiting” for two weeks and found that “bed rest is not a more effective therapy than watchful waiting.” Nor is less effective. The results were exactly the same. If that sounds like no big deal, consider the difference in the lives of those patients! Two weeks of bed rest? Compared to two weeks of going about your business!

Exercise is the closest thing there is to a miracle cure in musculoskeletal medicine (or any kind of medicine).2627 Rather than bed rest, you should try to stay as active as possible, mostly working within the limits imposed by the pain. As shown by Fernandez et al. (covered above), this is probably just as good as surgery for most people, certainly in the long run. Also, you don’t need to bother with any special “technical” therapeutic exercises (like core strengthening, training specific muscles, or working on coordination) — also shown by Fernandez et al. (in a different paper in 2015).28 Supervised, “structured” therapeutic exercise — allegedly tailored for the treatment of back pain and sciatica — are only slightly more effective than simply advising patients to stay active in the short term … and no difference at all in the long term).

So you might get a little bit of an edge by getting a physical therapist to give you a rehab regimen, but not a big one. But if you find it hard to be active at the best of time, perhaps the investment in some expert assistance is valuable for motivation and focus if nothing else!

But you can also just “keep it simple stupid,” and a great example is to do mobilization exercise …

Use it or lose it: mobilizations are the simplest form of structured therapeutic exercise

Mobilizations are basically active or “dynamic” stretches and rhythmical movements that “massage” your muscles and joints with movement — wiggle therapy. It involves a lot of moving a joint through its full range, without resistance — an easy exercise. What makes it a therapeutic is a little bit of method: systematically and repetitively exploring range of motion.

For sciatica, just move your hips and low back in as many ways as you can think of: toe touches, swinging your hips in circles, lunges, etc. Figure how far you can comfortable move your low back, pelvis, and hip joints and then go up to the edge again and again. A mobilizations regimen for chronic sciatica might involve a 10 minute ritual a couple times per day of batches of hip circles, toe touches, and lunges.

Read more about mobilizations.

Stretching

When stretching for sciatica, please stretch gently and calmly: the piriformis muscle, which may be producing the pain directly or indirectly, tends to be reactive in character. It needs to be gentled. The focus of the stretching should be neurological, not mechanical — that is, slowly get the muscle “used to” a greater length and lower tone.

Piriformis stretch, seated — starting from a seated position, place your ankle (on the side you’re stretching) over the opposite knee. Let your lifted knee relax downwards for a moment, and then begin to lean forward from your pelvis. Avoid simply slumping forward, which is useless. The image that is the key to this stretch is to “push your belly button between your legs.”

Posture and ergonomics

Ordinary sitting involves significant spinal flexion near the end of the lumbar spine range of motion, and could conceivably constitute “poor posture.” The tissue stagnancy of long hours in a chair, suspected of being unhealthy in other ways, seems like another obvious cause for concern. And yet … back pain and sciatica are actually not linked to sitting a lot.

People who sit a great deal in ordinary chairs at work have, at worst, only slightly more back pain than people who get more activity and stand more at work29 — but many studies have found no evidence of this at all.3031 And if seriously chronic stagnant spinal flexion isn’t a problem, or not much of one, probably no other minor poor posture is either.

Sciatica and “back pain” aren’t synonymous, and because sciatica may involve disc herniation that can be slightly aggravated by spinal flexion, sitting probably is more of a problem for some sciatica patients. If sitting makes your pain worse, avoid it! But sitting a lot should be regarded more as an aggravating factor to minimize during recovery than a cause of sciatica to be worried about avoiding long term — an important distinction.

Obviously awkward postures are a problem, and so is vibration, exemplified in helicopter pilots, who get about four times more back pain than most people.32 It makes complete sense to try to fix any challenging or awkward posture that you are forced to deal with regularly — but that’s so obvious it hardly needs to be said. If it’s not obvious, it’s probably not a problem.

There’s no evidence that sciatica is caused by any common ergonomic deficiency in office chairs, no evidence that any kind of chair — no matter how special or clever — can prevent or treat back pain. If you like fine and comfy office chairs, by all means treat yourself to a fancy ergonomic chair. But don’t buy it to help with your sciatica!

If you have a chair that specifically seems to aggravate your sciatica, by all means replace it — just replace it with an ordinary chair that doesn’t aggravate your sciatica.

Despite the lack of a link between sitting too much and back pain, I still recommend that people take frequent microbreaks from sitting and use them to exercise gently — small batches of rhythmic stretches are the most practical — because even if sitting still a lot isn’t the problem, activity is one of the best possible ways to deal with all kinds of pain. And sitting too much is generally a bad idea.

I’ve just summarized a lot of ideas that are covered in much more detail elsewhere on the site about posture, microbreaking, mobilizations and excessive sitting.

Pain-killing drugs

Nothing you can swallow is likely to significantly relieve sciatica pain. However, even a little benefit is better than nothing, and it’s worth experimenting — as long as you know how to do it safely. If you do discover a specific pain-killer works even a little better than the others, that can be quite valuable over the years. It’s worth paying close attention to using each major type of pain-killer on at least three occasions.

Over-the-counter pain medications are fairly safe and somewhat effective in moderation and work in different ways, which is why experiment is required. There are four main kinds: acetaminophen/paracetamol (Tylenol, Panadol), plus three non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs): aspirin (Bayer, Bufferin), ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), and naproxen (Aleve, Naprosyn).

Please do not take any of them chronically — risks go up over time, and they can even backfire and cause rebound headaches.

Acetaminophen is good for both fever and pain, and is one of the safest of all drugs at recommended dosages, but it may not work well for musculoskeletal pain (at all?) and overdose can badly hurt livers. The NSAIDs all reduce inflammation as well as pain and fever, but at any dose they can cause heart attacks and strokes and they are “gut burners” (they irritate the GI tract, even taken with food). Aspirin may be best for joint and muscle pain, but it’s the most gut-burning of them all.

Naproxen specifically may be the best anti-inflammatory drug for back pain without sciatica33 — but there is no clear alternative for back pain with sciatica, so in the absence of any other guideline, I’d prioritize naproxen.

Voltaren is an ointment NSAID, effective for superficial joint pain and quite a lot safer than oral NSAIDs.34 It’s so safe that it’s almost always worth experimenting with, but unfortunately sciatica is one of the least likely kinds of pain to be affected by a topical pain-killer: the tissues you want to affect are quite deep, and may not be reached by a drug that has to be absorbed through the skin.

For extremely severe sciatica — the kind that sends you to the hospital — intravenous corticosteroids are the best option, the most potent anti-inflammatory option there is.35 I’m pointing that out mainly because steroids are notably preferable to opioids for musculoskeletal pain, which are not nearly as potent as widely believed.36 It also suggests the importance of inflammation in acute, severe sciatica.

For more information about all kinds of pain-killers, see The Science of Pain-Killers: A user’s guide to over-the-counter analgesics like acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and more.

About Paul Ingraham

I am a science writer in Vancouver, Canada. I was a Registered Massage Therapist for a decade and the assistant editor of ScienceBasedMedicine.org for several years. I’ve had many injuries as a runner and ultimate player, and I’ve been a chronic pain patient myself since 2015. Full bio. See you on Facebook or Twitter., or subscribe:

What’s new in this article?

Twelve updates have been logged for this article since publication (2006). All PainScience.com updates are logged to show a long term commitment to quality, accuracy, and currency. more

When’s the last time you read a blog post and found a list of many changes made to that page since publication? Like good footnotes, this sets PainScience.com apart from other health websites and blogs. Although footnotes are more useful, the update logs are important. They are “fine print,” but more meaningful than most of the comments that most Internet pages waste pixels on.

I log any change to articles that might be of interest to a keen reader. Complete update logging of all noteworthy improvements to all articles started in 2016. Prior to that, I only logged major updates for the most popular and controversial articles.

See the What’s New? page for updates to all recent site updates.

Dec 3, 2024 — Added a comprehensive list of the major diagnostic possibilities.

2021 — Small but valuable safety update: better red flag information based on Angus et al.

2020 — Added more detail about pain-killers, and more and better information about the role of herniation (with upgraded citations).

2019 — Added discussion of cluneal nerve entrapment and trochanter pain syndrome to the diagnosis section.

2018 — Rewrote the introduction to fine tune the definition of sciatica, and the diagnosis section based on a fascinating study, Konstantinou et al. Although there’s no major changes of position in this update, it is quite substantive: the article is definitely better for it.

2017 — New section: “Disc herniations are much less of a problem than most people think.”

2017 — Exercise and surgery updates related to two valuable new citations, both from Fernandez et al. Improved the mobilizations section especially.

2017 — Threw out the stale, simple old section about posture and ergonomics and wrote a completely new one.

2016 — Minor update. Edited sciatica surgery section.

2015 — Added a section about over-the-counter pain-killers.

2011 — Corrected some minor technical errors.

2011 — Added reference concerned genetic causes of chronic nerve pain.

2010 — Added information debunking bed rest as a treatment option.

2008 — Revisions are moving slowly! However, added a major new section today, “What about surgery?” which is based on some excellent new research evidence from Dutch scientists. Made a few other minor improvements at the same time.

2007 — Began revisions by doing a wide variety of minor improvements to the introductory sections.

2006 — Publication.

Related Reading

- Just in case I haven’t convinced you yet, this article really is not ideal for you if sciatica is only part of your back pain. If you have back pain, please read The Complete Guide to Low Back Pain — An extremely detailed guide to the myths, controversies, and treatment options for low back pain. Also, at this time, that article is much more thorough than this one, and covers many similar concepts. The two conditions are closely related.

- The Chiropractic Controversies — An introduction to chiropractic controversies like aggressive billing, treating kids, and neck manipulation risks

- The Complete Guide to Trigger Points & Myofascial Pain — An extremely detailed guide to the unfinished science of muscle pain, with reviews of every theory and treatment option

- Massage Therapy for Low Back Pain — Perfect Spot No. 2, in the erector spinae and quadratus lumborum muscles in the thoracolumbar corner

- Massage Therapy for Back Pain, Hip Pain, and Sciatica — Perfect Spot No. 6, an area of common trigger points in the gluteus medius and minimus muscles of the hip

Notes

- Konstantinou K, Lewis M, Dunn KM. Agreement of self-reported items and clinically assessed nerve root involvement (or sciatica) in a primary care setting. Eur Spine J. 2012 Nov;21(11):2306–15. PubMed 22752591 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 52894 ❐ More on this interesting study coming later in the article.

- Ropper AH, Zafonte RD. Sciatica. N Engl J Med. 2015 Mar;372(13):1240–8. PubMed 25806916 ❐

- Stafford MA, Peng P, Hill DA. Sciatica: a review of history, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and the role of epidural steroid injection in management. Br J Anaesth. 2007 Oct;99(4):461–73. PubMed 17704089 ❐

- These are the signatures of infections and tumours. They often have other symptoms that make it obvious there’s something more sinister going on, but not always — but they do usually just get worse and worse.

- Angus M, Curtis-Lopez CM, Carrasco R, et al. Determination of potential risk characteristics for cauda equina compression in emergency department patients presenting with atraumatic back pain: a 4-year retrospective cohort analysis within a tertiary referral neurosciences centre. Emerg Med J. 2021 Oct. PubMed 34642235 ❐ The traditional red flags for cauda equina syndrome — trouble with the lowest parts of the spinal column — are numbness around the anus and groin, and some incontinence. But these symptoms are actually just as common in people without CES. In fact, this 2021 data shows that many CES symptoms are like that, and the only ones that are somewhat more reliable indicators are pain and weakness in both legs, plus (to a lesser degree) difficulty urinating — but even those also often occur without CES that can be confirmed on imaging.

- Halpin RJ, Ganju A. Piriformis syndrome: a real pain in the buttock? Neurosurgery. 2009 Oct;65(4 Suppl):A197–202. PubMed 19927068 ❐ “There is no definitive proof of its existence despite reported series with large numbers of patients.”

- Natsis K, Totlis T, Konstantinidis GA, et al. Anatomical variations between the sciatic nerve and the piriformis muscle: a contribution to surgical anatomy in piriformis syndrome. Surg Radiol Anat. 2014 Apr;36(3):273–80. PubMed 23900507 ❐

This dissection study of 275 dead buttocks found that 6.4% of them had variations of sciatic nerve and piriformis muscle anatomy, with considerable variety in the variation. They found several different arrangements, and concluded: “Some rare, unclassified variations of the sciatic nerve should be expected during surgical intervention of the region.” Prepare to be surprised, surgeons!

All of these differences are potentially clinically significant, probably especially in the cases where the nerve (or part of it) passes right through the muscle. For a couple case studies, see Arooj 2014 and Kraus 2015.

- Migliorini S, Merlo M. The hamstring syndrome in endurance athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(4):363. PubMed 3594312 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 54078 ❐

- Aota Y. Entrapment of middle cluneal nerves as an unknown cause of low back pain. World J Orthop. 2016 Mar;7(3):167–70. PubMed 27004164 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 53097 ❐

- Anything good for your general health has the potential to help chronic pain. The specific cause of chronic pain may often be less important than general sensitivity and biological vulnerability to any pain. The biggest risk factors for pain chronicity are things like insomnia, obesity, smoking, drinking… and they overshadow common scapegoats like poor posture, spinal degeneration, or even repetitive strain injury. How can nothing in particular make us hurt? Because pain is weird, a generally oversensitive alarm system that can produce false alarms even at the best of times, and probably more of them when your system is under strain. See Vulnerability to Chronic Pain: Chronic pain often has more to do with general biological vulnerabilities than specific tissue problems.

- Zhong M, Liu JT, Jiang H, et al. Incidence of Spontaneous Resorption of Lumbar Disc Herniation: A Meta-Analysis. Pain Physician. 2017;20(1):E45–E52. PubMed 28072796 ❐

- Konstantinou 2012, op. cit.

- This is why I am cautious with to avoid anything like diagnosis-by-email, despite being more or less constantly asked for it. Readers send me “descriptions” of their pain problems, routinely with the considerate disclaimer that they “don’t expect a diagnosis,” when what they really mean is, “I realize I can’t hold you to it, but I want a diagnosis anyway.” Many of them are articulate and give perfectly nice descriptions. Many more seem to be sworn enemies of clear writing, and my chance of having a clue what they are talking about based on their email is approximately zero percent. And so it goes.

- Torun F, Dolgun H, Tuna H, et al. Morphometric analysis of the roots and neural foramina of the lumbar vertebrae. Surgical Neurology. 2006 Aug;66(2):148–51; discussion 151. PubMed 16876606 ❐ This was exasperatingly hard data to find for some reason, and the paper abstract begins by saying so: “There have been few anatomic studies on the foramina and roots of the lumbar region … .” This is in a 2006 paper! Hardly ancient.

- Takasaki H, Hall T, Jull G, et al. The influence of cervical traction, compression, and spurling test on cervical intervertebral foramen size. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009 Jul;34(16):1658–62. PubMed 19770608 ❐

- Sari H, Akarirmak U, Karacan I, Akman H. Computed tomographic evaluation of lumbar spinal structures during traction. Physiother Theory Pract. 2005;21(1):3–11. PubMed 16385939 ❐

- Ebraheim NA, Liu J, Ramineni SK, et al. Morphological changes in the cervical intervertebral foramen dimensions with unilateral facet joint dislocation. Injury. 2009 Nov;40(11):1157–60. PubMed 19486975 ❐

Researchers dislocated neck joints in corpses to measure the effect on the size of the intervertebral foramina. (Interesting chore!) Dislocation made the spaces quite a bit larger, indicating that any nerve root pain associated with these injuries “is probably due to distraction rather than due to direct nerve root compression.”

- Peul WC, van den Hout WB, Brand R, et al. Prolonged conservative care versus early surgery in patients with sciatica caused by lumbar disc herniation: two year results of a randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008 Jun;336(7657):1355–8. PubMed 18502911 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 53367 ❐ The authors of this paper write, “At the two year assessment only 80% of all patients reported that they had recovered. Some patients who had reported complete recovery within a year of randomisation later apparently had recurrent symptoms of leg or back pain and, at two years’ follow-up, experienced no improvement or even deterioration compared with their pre-randomisation status. Physicians guiding patients with sciatica should remember that the long term prognosis may be less favourable than is suggested by the first impression after successful treatment.”

- Costigan M, Belfer I, Griffin RS, et al. Multiple chronic pain states are associated with a common amino acid-changing allele in KCNS1. Brain. 2010 Sep;133(9):2519–27. PubMed 20724292 ❐

Mark your calendars: 2010 was the year researchers confirmed a gene as “one of the first prognostic indicators of chronic pain risk,” doubling or tripling the odds that a low back pain patient will recover in a timely fashion from nerve root injury. Screening for this gene is not yet something that is clinically available, but it probably will be someday, and then you will know: the universe really does hate you.

- Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: Implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain. 2010 Oct;152(2 Suppl):S2–15. PubMed 20961685 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 54851 ❐

Pain itself often modifies the way the central nervous system works, so that a patient actually becomes more sensitive and gets more pain with less provocation. That sensitization is called “central sensitization” because it involves changes in the central nervous system (CNS) in particular — the brain and the spinal cord. Victims are not only more sensitive to things that should hurt, but also to ordinary touch and pressure as well. Their pain also “echoes,” fading more slowly than in other people.

For a much more detailed summary of this paper, see Sensitization in Chronic Pain.

- Fernandez M, Ferreira ML, Refshauge KM, et al. Surgery or physical activity in the management of sciatica: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Spine J. 2016 Nov;25(11):3495–3512. PubMed 26210309 ❐

Based on a review of twelve mediocre trials, surgery for disc herniation causing sciatica is, at best, only a modestly superior treatment to physical activity and only in the short term; in the long term, there’s no important difference. Surgery for stenosis and spondylolisthesis was more decisively superior to exercise in the short and long term, but this good news still cannot be trusted. We need to take any seemingly good news about surgery with a grain of salt. Conclusions based on anything less than data from placebo-controlled trials is highly suspect, as shown ad nauseam about several other orthopedic surgeries (see Louw et al. and related papers). This good-ish news is mostly based on comparative benefits, patient reported outcomes, and cost analyses … and that’s just not good enough anymore. Garbage in, garbage out!

- Peul WC, van den Hout WB, Brand R, et al. Prolonged conservative care versus early surgery in patients with sciatica caused by lumbar disc herniation: two year results of a randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008 Jun;336(7657):1355–8. PubMed 18502911 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 53367 ❐

- Louw A, Diener I, Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Puentedura EJ. Sham Surgery in Orthopedics: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Pain Med. 2016 Jul. PubMed 27402957 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 53458 ❐

This review of a half dozen good quality tests of four popular orthopedic (“carpentry”) surgeries found that none of them were more effective than a placebo. It’s an eyebrow-raiser that Louw et al. could find only six good (controlled) trials of orthopedic surgeries at all — there should have been more — and all of them were bad news.

The surgeries that failed their tests were:

- vertebroplasty for osteoporotic compression fractures (stabilizing crushed verebtrae)

- intradiscal electrothermal therapy (burninating nerve fibres)

- arthroscopic debridement for osteoarthritis (“polishing” rough arthritic joint surfaces)

- open debridement of common extensor tendons for tennis elbow (scraping the tendon)

Surgeries have always been surprisingly based on tradition, authority, and educated guessing rather than good scientific trials; as they are tested properly, compared to a placebo (a sham surgery), many are failing. This review of the trend does a great job of explaining the problem. This is one of the best academic citations to support the claim that “sham surgery has shown to be just as effective as actual surgery in reducing pain and disability.” The need for placebo-controlled trials of surgeries (and the damning results) is explored in much greater detail — and very readably — in the excellent book, Surgery: The ultimate placebo, by Ian Harris.

- The Vancouver Aquatic Centre (downtown on Beach Avenue, beside the Burrard Street Bridge) has a hot tub with unusually powerful jets. They are really incredible! In fact, they may be too incredible for a bad case of sciatica: but once it starts healing, the strength of these jets is very helpful.

- Vroomen PC, de MC Krom, Wilmink JT, Kester AD, Knottnerus JA. Lack of effectiveness of bed rest for sciatica. N Engl J Med. 1999 Feb 11;340(6):418–23. PubMed 9971865 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 56953 ❐

- Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. Exercise: The miracle cure and the role of the doctor in promoting it. AOMRC.org.uk. 2015 Feb. PainSci Bibliography 53672 ❐

This citation is the primary authoritative source of the quote “exercise is the closest thing there is to a miracle cure” (although there are no doubt many variations on it from other sources over the years).

- Gopinath B, Kifley A, Flood VM, Mitchell P. Physical Activity as a Determinant of Successful Aging over Ten Years. Sci Rep. 2018 Jul;8(1):10522. PubMed 30002462 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 53004 ❐

If you want to age well, move around a lot!

We already know that physical activity reduces the risk of several of the major chronic diseases and increases lifespan. “Successful aging” is a broader concept, harder to measure, which encompasses not only a reduced risk of disease but also the absence of “depressive symptoms, disability, cognitive impairment, respiratory symptoms and systemic conditions.” (No doubt disability from pain is part of that equation.)

In this study of 1584 older Australians, 249 “aged successfully” over ten years. The most active Aussies, “well above the current recommended level,” were twice as likely to be in that group. Imagine how much better they’ll do over 20 years …

- Fernandez M, Hartvigsen J, Ferreira ML, et al. Advice to Stay Active or Structured Exercise in the Management of Sciatica: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015 Sep;40(18):1457–66. PubMed 26165218 ❐

- Hartvigsen J, Leboeuf-Yde C, Lings S, Corder EH. Is sitting-while-at-work associated with low back pain? A systematic, critical literature review. Scand J Public Health. 2000 Sep;28(3):230–9. PubMed 11045756 ❐

This review of 35 scientific papers (8 of them high quality) about sitting-while-at-work as a risk factor for low back pain found that the “extensive recent epidemiological literature does not support the popular opinion that sitting-while-at-work is associated with LBP.”

- Bakker EWP, Verhagen AP, van Trijffel E, Lucas C, Koes BW. Spinal mechanical load as a risk factor for low back pain: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009 Apr;34(8):E281–93. PubMed 19365237 ❐

This review of 18 studies of risk factors for low back pain confirmed strong evidence of no link to sitting, standing, walking, or common amateur sports; “conflicting” evidence about leisure activitiues like gardening, whole body vibration, hard physical work, and even “working with ones trunk in a bent and/or twisted position”; and no evidence of any quality about sleeping.

- Chen SM, Liu MF, Cook J, Bass S, Lo SK. Sedentary lifestyle as a risk factor for low back pain: a systematic review. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2009 Jul;82(7):797–806. PubMed 19301029 ❐

- Lis AM, Black KM, Korn H, Nordin M. Association between sitting and occupational LBP. Eur Spine J. 2007 Feb;16(2):283–98. PubMed 16736200 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 53732 ❐

- Ashbrook J, Rogdakis N, Callaghan MJ, Yeowell G, Goodwin PC. The therapeutic management of back pain with and without sciatica in the emergency department: a systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2020 Jul;109:13–32. PubMed 32846282 ❐ “Evidence suggests that Naproxen alone should be considered as first line management in cases of back pain without sciatica.”

- Derry S, Moore RA, Gaskell H, McIntyre M, Wiffen PJ. Topical NSAIDs for acute musculoskeletal pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;6:CD007402. PubMed 26068955 ❐

- Ashbrook 2020, op. cit.

- Berthelot JM, Darrieutort-Lafitte C, Le Goff B, Maugars Y. Strong opioids for noncancer pain due to musculoskeletal diseases: Not more effective than acetaminophen or NSAIDs. Joint Bone Spine. 2015 Oct. PubMed 26453108 ❐ Several other sources of evidence are explored in my article all about opioids.