Get in the Pool for Pain

Aquatic therapy, aquajogging, water yoga, floating and other water-based treatment and injury rehab options

Anyone with almost any kind of chronic pain should consider spending more time in the pool — doing almost anything! Aquajogging is a particularly good choice.1 This advice is for many patients who might not consider pool therapy.

Aquatic therapy can be great for almost any kind of stubborn pain. Immersion and flotation may have curiously strong benefits. The relief from gravity, that most relentless of all physical stresses, is valuable both as actual mechanical security and to make movement feel easy, cushioned, and safe — and feeling safer with movement can be a critical stepping stone in all kinds of rehabilitation and pain management.

Pain is an expression of perceived danger to the system.2 Pools are one of the few places where we can both be more active while also actually feeling safer. That’s a precious combination. There are some other helpful biological effects of immersion, too: the human nervous system really seems to like it.

But it’s not magic: studies have shown it’s no better than “dry” rehab for most problems.34 It’s not for everyone, and there are some downsides, like getting chilly (a deal-breaker for some chronic pain patients). However, it is well worth taking a shot at it and making the effort to make it work for you.5

Floating (deep and shallow)

The simplest aquatic therapy is to just float. There are two main kinds of flotation therapy, quite different experiences:

- Pool or hot tub floating in deeper water, ideally floating vertically so that more of your body is more deeply submerged, because it’s actually the water pressure that has a therapeutic benefit, and the deeper you go, the more pressure you get — exponentially more. Floating in deep water lowers heart rate by more than 10 beats per minute,67 and has curiously profound neurological effects.8

- Tank floating in shallow, high-buoyancy (salted) water — a super Epsom salt bath, basically, although the main goal is the floating, not the salt. (Epsom salts have no clear medical benefits, unfortunately.9) Water pressure is not a factor here at all, but the luxurious warmth, quiet, and sensory “deprivation”10 definitely is. (Note that float industry has moved away from small, coffin-like fibreglass flotation tanks, and many float spas now offer spacious, luxurious tubs.)

All of the above is potentially terrific for injury rehabilitation and chronic pain in many ways.

Just immersing yourself can lower your heart rate and has curiously profound neurological effects.

Aquajogging and water aerobics: don’t just float there, do something!

Aquajogging and water aerobics combine the benefits of vertical (deep) immersion with exercise, “the closest thing there is to a miracle cure.”1112

The lack of impact, the “cushioning,” and the ease of fine-tuning the intensity make it a fine place for garden variety rehab. But where aquatic therapy may shine brightest is with patients whose primary symptom is unexplained pain, like fibromyalgia.13 I’m not saying that the pool has any special properties that directly treat complex and chronic pain — although that is also possible — just that immersion facilitates exercise in patients that both particularly need it and struggle with it (a difficult benefit to measure).

Aquajogging works a lot better with the help of a simple accessory, a buoyancy belt like the AquaJogger or the WaterGym Water Float Belt (and many others, sometimes called a water aerobics belt). I recently encountered a fellow who was wearing one of these at the pool, and he claimed he’d had his for more than a decade: a good investment!

Oddly enough, I’d never heard of aquajogging until quite recently. Reader Jared Updike introduced me to it, and he’s a persuasive evangelist for it:

I would love for more people to know about aquajogging. It is a weirdly convenient form of swimming where you trade several pieces of equipment (goggles, hair cap, ear plugs, etc.) for a single strange piece of equipment (flotation belt) and in exchange your hair and eyes and ears stay dry and you can wear a hat and sunglasses while you slowly pull yourself across the pool. And it scales up or down for different fitness levels or pain-level fluctuations. It’s the closest thing to a silver bullet I have found for my pain and fatigue.

Read a more detailed guide to aquajogging.

Or you could just, you know, swim! Swimming itself is, of course, great exercise. If your body will tolerate it, it’s one of the best workouts you can do. But for chronic pain patients, the vertical immersion of aquajogging really is ideal.

Aqua therapy is helpful for Corgis too.

Water Yoga: 5 breathing and stretching exercises for the water

The popularity of yoga is almost oppressive. People feel that they “should” try yoga and may even feel guilty for not trying it (or not liking it). For people on the fence, a little water yoga might be more fun and easier to mess around with. 😃

I use a pool regularly for “yoga” rather than for swimming — a casual and unstructured yoga, but yoga nevertheless. Using the buoyancy of water to aid rehabilitation is a well-known and excellent idea, but the potential for your pool to be an excellent place to breathe and stretch is less widely appreciated. Here are five examples of exercises that make good use of the water:

The physics of water breathing

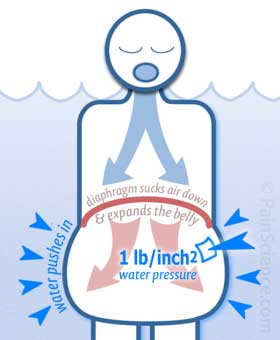

Water pressure resists expansion of the abdomen uniformly on all sides — and therefore it resists diaphragm contraction.

- Diaphragmatic breathing. Water pressure is surprisingly strong even just a couple feet down. This provides strong resistance to abdominal expansion … and you can seriously dial up the diaphragm workout by adding a snorkel or longer breathing tube and sinking just a little further into the water, thanks to the magic of pressure math.14 Note that there are some safety issues here, so please be sensible.15 A nice variation is to do an abdominal lift or lock exercise (uddiyana bandha).

- Floating forward bend, a watered-down version (ha ha!) of the big toe pose (padangusthasana, similar to the better-known simple standing forward bend or uttanasana). Simply take a deep breath — your head will be underwater! — and fold in half at the waist, grasp your big toes, and pull your head down towards your knees. You will bob like a cork as you stretch!

- The bow pose (dhanurasana) is much more comfortable in a pool than when you are fighting gravity — the strength required to get into and sustain these poses can make it unpleasant. In the pool, you can enjoy the best sensations the pose has to offer … and you can be even more bow-like. (Bow-ish? Bowly? Bowed?) Take a good deep breath — you will may need hold the air in your lungs to float high enough in the water — reach down and pull one leg up behind you by the ankle, then the other, and then arch your back. Let your air-filled chest keep you afloat.16

- Dead float. Nothing beats floating for deep relaxation. A watery version of yoga’s corpse pose (savasana), floating perfectly still is lovely. Of course this works best if you’re nice and warm after a session in the hot tub, and a really great refinement is to have a partner slightly support you and move you around in the water. Do be aware that someone may think you are drowning!17

- Sinking meditation. Okay, perhaps I’m kinda weird — undoubtedly I am — but I think it’s really neat to sink to the bottom of the pool and meditate while holding my breath. Yes, I really do this. No, they aren’t long meditations! But I’m a busy guy and I don’t like long meditations anyway. Pool bottoms are peaceful places, and slowly sinking to the bottom is a strong metaphor for descent into an altered state. For the best results, you have to do something counterintuitive: you have to exhale most of your breath, and hold your breath at the bottom (in two senses). This may seem alien at first, but it works better than you think it will. I’ve been practicing this for a long time, and it’s no problem for me to do a couple minutes.18

Yoga and stretching are not everything they are cracked up to be, and they probably fail to achieve much of what people are hoping for — such as preventing muscle soreness,19 or curing low back pain.20 But I am not anti-stretching: it feels great, and not only is that sufficient reason in itself, it probably does mean it’s doing something valuable for us biologically, even if it’s surprisingly unclear exactly what. Here’s an interesting clue: a 2011 study showed that a program of static stretching alone — just pulling on muscles — had a clear benefit for heart rate regulation, a common way of measuring fitness.21 Bodies probably need constant sensory feedback for optimum function — use it or lose it — and this evidence is probably a nice demonstration of that principle.

Deeper mysteries

I asserted above that immersion has “curiously potent benefits” and “the human nervous system really seems to like it,” but then I got on with the sobering scientific details: it obviously doesn’t work any miracles in rehab. So what’s the basis of my claims that there’s something more profound going on?

For me, it began with a bizarre personal experience: a serious chronic neck pain simply vanished when I was submerged in a pool. Outside the pool, tipping my head forward or to the left always hurt, without fail. But if I got in the water and dunked my head, it was simply gone, and the effect was completely reliable over days and weeks.

This almost magical effect was inconvenient without a snorkel, so I upgraded to a snorkel, and then to experimentation with more flexible breathing tubes of various diameters. It didn’t entirely solve the problem out of the water, but it did help. You can read the whole peculiar story here: Neck Pain, Submerged! The story of my curious experiment with dunking severe chronic neck pain.

That bizarre effect was my first clue that immersion can sometimes do marvellous things. But that’s nothing compared to the next example.

Complete relief from severe unexplained symptoms

Julie Rehmeyer felt like she was going to die. She had spent years battling a mysterious illness so extreme that she often couldn’t turn over in her bed. The top specialists in the world were powerless to help. Unlike most victims of this strange disease, Rehmeyer is a science journalist, largely immune to the siren song of snake oils. She took an extraordinarily rational approach to her problem, and wrote a really good book about her journey.22 I was surprised to find this:

I discovered my most effective management tool through serendipity, when William and I visited a hot springs resort in the Sierras.

As always, I’d imagined that I’d catch an upswing and be able to tramp through the snow under the great dark pine trees, but in fact, short walks were the best I could manage, and my paralysis came on several times. We hung out at the hot springs and in the body-temperature pool next to it, where I listlessly floated on my back in the womblike embrace of the warm water. I looked at the trees towering above me, imagining the energy flowing through them into the sky, their sap traveling a hundred feet up through their sturdy trunks despite the freezing cold. Every tree felt like an unattainable miracle of verticality and life force.

After paddling around for a bit, I prepared myself to stagger back to the locker room—but when I got out, the problem had disappeared. Thanks for the break, Greek gods, I thought. The next time I was paralyzed, I floated in the warm pool again, and again, I was able to walk. A third time too. Hmm …

This turned out to be a reliable miracle.

It wasn’t a cure for her anymore than my weird immersion experiment fixed my neck pain. But the phenomenon was profound and vivid, and it really was her “most effective management tool” — indeed, really the only really effective one she discovered. There’s even a potentially good explanation for it, which Rehmeyer doesn’t get into: the mechanism could be temporary relief from positional spinal cord compression, a newly discovered culprit in some cases of medically unexplained symptoms, including severe chronic pain and fatigue.23

Regardless of what was going on, the story has some tantalizing and important implications. Clearly, strange and good things can happen in the water.

Did you find this article useful? Interesting? Maybe notice how there’s not much content like this on the Internet? That’s because it’s crazy hard to make it pay. Please support (very) independent science journalism with a donation. See the donation page for more information & options.

About Paul Ingraham

I am a science writer in Vancouver, Canada. I was a Registered Massage Therapist for a decade and the assistant editor of ScienceBasedMedicine.org for several years. I’ve had many injuries as a runner and ultimate player, and I’ve been a chronic pain patient myself since 2015. Full bio. See you on Facebook or Twitter., or subscribe:

Related Reading

- Neck Pain, Submerged! — The story of my curious experiment with dunking severe chronic neck pain

- Hydrotherapy, Water-Powered Rehab — A guide to using warm and cold water as a treatment for pain and injury

- Does Epsom Salt Work? — The science and mythology of Epsom salt bathing for recovery from muscle pain, soreness, or injury

- Hot Baths for Injury & Pain — Tips for getting the most benefit from a hot soak, the oldest form of therapy

- Ugly Bags of Mostly Water — The chemical composition of human biology

- Water Fever and the Fear of Chronic Dehydration — Do we really need eight glasses of water per day?

What’s new in this article?

Four updates have been logged for this article since publication (2017). All PainScience.com updates are logged to show a long term commitment to quality, accuracy, and currency. more

Like good footnotes, update logging sets PainScience.com apart from most other health websites and blogs. It’s fine print, but important fine print, in the same spirit of transparency as the editing history available for Wikipedia pages.

I log any change to articles that might be of interest to a keen reader. Complete update logging started in 2016. Prior to that, I only logged major updates for the most popular and controversial articles.

See the What’s New? page for updates to all recent site updates.

2019 — New section, “Deeper mysteries,” about hard-to-explain effects of immersion on severe chronic pain and fatigue.

2019 — Some editing and minor corrections.

2017 — Science updated. Added a couple key citations about the efficacy of aquatic therapy, and spelling out the case for it a bit more.

2017 — Added a footnote with some tips about how to cope with getting chilly in pools.

2017 — Publication.

Notes

Swim England is all about promoting swimming, so it’s hardly an unbiased source on this topic, but I don’t really doubt the very positive gist of the findings of a 2017 report they commissioned:

The report particularly highlights the benefits of swimming and aquatic activities for people with mental health concerns or problems with their joints and muscles.

- Modern pain science shows that pain is an extremely unpredictable sensation, heavily tuned by the brain and jostled by complex variables — not the relatively simple response to tissue insult that we tend to assume, and that most treatment is based on. For more information, see Pain is Weird: Pain science reveals a volatile, misleading sensation that comes entirely from an overprotective brain, not our tissues.

- Villalta EM, Peiris CL. Early aquatic physical therapy improves function and does not increase risk of wound-related adverse events for adults after orthopedic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013 Jan;94(1):138–48. PubMed 22878230 ❐

A review of 8 tests of aquatic physical therapy after orthopedic surgeries found that it was safe and at least as effective as land-based therapy. Unfortunately, it showed no superiority for swelling and pain, benefits that might be needed to justify the cost and hassle.

- Barker AL, Talevski J, Morello RT, et al. Effectiveness of aquatic exercise for musculoskeletal conditions: a meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014 Sep;95(9):1776–86. PubMed 24769068 ❐

A review of 26 tests of aquatic therapy for miscellaneous musculoskeletal conditions. The results are similar to Villalta et al. (for rehab after surgical): at least as good as land-based therapy, but no better (alas).

- Try different pools — they aren’t all the same temperature! Call and ask (there’s usually a temperature every facility aims for). And consider a wetsuit. Such solutions might sound like overkill, but what’s worse: buying and maintaining a wetsuit or two? Driving a little? Or abandoning an excellent treatment option for your chronic pain? (Hat tip to reader Jared Updike for these suggestions — I wholeheartedly agree.)

- Cuesta-Vargas A, Garcia-Romero JC, Kuisma R. Maximum and Resting Heart Rate in Treadmill and Deep-Water Running in Male International Volleyball Players. International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education. 2009;3:398–405.

In this simple test of several volleyball players, running in water resulted in a much lower maximum heart rate and recovery heart rate than running on a treadmill: a clear “cardiovascular response mediated by immersion in water.”

- Mourot L, Teffaha D, Bouhaddi M, et al. Exercise rehabilitation restores physiological cardiovascular responses to short-term head-out water immersion in patients with chronic heart failure. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2010;30(1):22–7. PubMed 20068419 ❐

In patients with coronary artery disease, short-term head-out water immersion had several significant effects on circulatory function, especially, including a significantly decreased pulse rate, both before and after a rehabilitation program. Patients with chronic heart failure were initially unaffected by immersion, but “restored the usual central responses.” Arterial compliance was the only hemodynamic factor that was not affected by immersion.

- Schipke JD, Pelzer M. Effect of immersion, submersion, and scuba diving on heart rate variability. Br J Sports Med. 2001 Jun;35(3):174–80. PubMed 11375876 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 53699 ❐

Heart rate variability (HRV) refers to the slight wobbles in the rhythm of the heart, tiny variations in the time between beats. Curiously, this is a good indicator of neurological relaxation or arousal, messy and complex but reliable. For this test, HRV was measured in twenty-five scuba divers in head-out immersion and while diving in a pool (27˚C). They found that “all HRV measures showed an increase in the parasympathetic activity” (relaxation) and “immersion under pool conditions is a powerful stimulus for both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system.” Fascinating!

Epsom salt (magnesium sulfate) probably doesn’t do anything you hope it’s doing. It is at least cheap and harmless and it makes the water feel “silkier,” but — contrary to very popular belief — it probably has no significant benefits for most common kinds of aches and pains. Most theories you hear about how Epsom salt baths work are oversimplified and meaningless. For instance, nearly everyone says it is absorbed by osmosis, which is very wrong; and there’s also no way it is “detoxifying” in any sense. Oral and nutritional magnesium supplementation may be helpful for some types of chronic pain for some people with magnesium deficiency, but digesting it probably works much better than trying to soak in it. Even topical delivery via creams is scientifically controversial, but absorption from baths is virtually unstudied: it may not work in a bath at all, or only modestly and erratically. The soothing heat of a nice bath is probably more therapeutic than whatever magnesium might be absorbed. Bathing in a magnesium sulfate solution also has no other known medical benefits other than possibly treating skin infections. The case for the healing powers of Epsom salt is mostly made by people selling the stuff, plus a few biologically illiterate alternative medicine practitioners keen on reinforcing their brand by prescribing “natural” remedies. If relatively dilute home salt baths were actually medicinal, then far more concentrated sources like The Dead Sea would have clear health effects, which they definitely do not. For more information, see Does Epsom Salt Work? The science and mythology of Epsom salt bathing for recovery from muscle pain, soreness, or injury.

- Although a quiet, dark flotation tank certainly deprives us of our normal sensations, by no means are we actually deprived. It actually constitutes a pleasant, novel sensory experience, not “deprivation.”

- Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. Exercise: The miracle cure and the role of the doctor in promoting it. AOMRC.org.uk. 2015 Feb. PainSci Bibliography 53672 ❐

ABSTRACT

The big four “proximate” causes of preventable ill-health are: smoking, poor nutrition, lack of physical activity and alcohol excess. Of these, the importance of regular exercise is the least well-known. Relatively low levels of increased activity can make a huge difference. All the evidence suggests small amounts of regular exercise (five times a week for 30 minutes each time for adults) brings dramatic benefits. The exercise should be moderate – enough to get a person slightly out of breath and/or sweaty, and with an increased heart rate. This report is a thorough review of that evidence.

Regular exercise can prevent dementia, type 2 diabetes, some cancers, depression, heart disease and other common serious conditions — reducing the risk of each by at least 30%. This is better than many drugs.

- Gopinath B, Kifley A, Flood VM, Mitchell P. Physical Activity as a Determinant of Successful Aging over Ten Years. Sci Rep. 2018 Jul;8(1):10522. PubMed 30002462 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 53004 ❐

If you want to age well, move around a lot!

We already know that physical activity reduces the risk of several of the major chronic diseases and increases lifespan. “Successful aging” is a broader concept, harder to measure, which encompasses not only a reduced risk of disease but also the absence of “depressive symptoms, disability, cognitive impairment, respiratory symptoms and systemic conditions.” (No doubt disability from pain is part of that equation.)

In this study of 1584 older Australians, 249 “aged successfully” over ten years. The most active Aussies, “well above the current recommended level,” were twice as likely to be in that group. Imagine how much better they’ll do over 20 years …

- Fibromyalgia is extremely difficult to treat, but exercising in the goldilocks zone is the first line of defense. The pool is ideal in many ways.

- The weight of the water presses relentlessly inwards on every square inch of rib cage and belly, and the narrow diameter of the tube becomes the sole pressure outlet for the weight of all that water. Air whooshes out of your lungs and through the tube, unless you stop it. Put your tongue over the tube end, and you will notice a formidable suction. When you try to inhale through that tube, you have to first match the suction and then exceed it to get any air! It becomes well nigh impossible as you descend. For a more detail description of the physics, see the exercises at the end of the article The Respiration Connection.

- Blazingly obvious, disclaimery safety warnings: I am not responsible for you being foolish in the water. Don’t do this alone. Don’t do this in deep water. Don’t use too long/wide a tube for too long. Don’t keep going if you feel dizzy or nauseous. Don’t inhale water. Don’t chew gum while you’re doing this. Et cetera, et cetera.

- Although I mostly hold my breath to stay afloat, I find I can take quick breaths to sustain the pose. If I let out too much air for too long, though, I sink! Your mileage may vary.

- Reader George Ingham, formerly a lifeguard, tells me that “sometimes people would do a dead float without telling me about it,” resulting in embarrassing “rescues”!

- During my massage therapy career, I had a client who was an elite free diver; she regularly held her breath for about 6–7 minutes, and hung out with a free-diving crowd that was generally getting to 8. That’s still well short of what’s possible, but it still blows my mind. Almost unbelievably, as of 2023, the world record for breath-holding was 24 minutes and 37 seconds. Astonishing.

- A large 2011 review of all the available science to date concluded with a clear thumbs down: “The evidence from randomised studies suggests that muscle stretching, whether conducted before, after, or before and after exercise, does not produce clinically important reductions in delayed-onset muscle soreness in healthy adults.” See Herbert, or see my main stretching article for a lot more information like that: Quite a Stretch: Stretching science has shown that this extremely popular form of exercise has almost no measurable benefits.

- At best, yoga is probably no more than slightly better than nothing as a low back pain treatment — and a pair of studies found that yoga classes conveyed no more benefit than ordinary stretching and exercise classes, which was a bit of a blow to yoga pride. See Sherman et al.

- Farinatti PTV, Brandão C, Soares PPS, Duarte AFA. Acute effects of stretching exercise on the heart rate variability in subjects with low flexibility levels. J Strength Cond Res. 2011 Jun;25(6):1579–85. PubMed 21386722 ❐

This study of stretching found that

multiple-set flexibility training sessions enhanced the vagal modulation and sympathovagal balance [that’s good] in the acute postexercise recovery, at least in subjects with low flexibility levels. … stretching routines may contribute to a favorable autonomic activity change in untrained subjects.

This seems like a fairly straightforward bit of good-news science about stretching. It’s not a surprising idea that movement would have some systemic regulatory effects (motion is lotion, use it or lose it), but it’s nice to see some corroboration of that common sensical notion, and it’s also nice to know that perhaps just stretching did this (to the extent we can learn anything from a single study). If true, it makes for nice evidence to support a general stretching habit, yoga, mobilizations, really any kind of “massaging with movement,” and probably even massage itself.

- Rehmeyer J. Through the Shadowlands: A science writer's odyssey into an illness science doesn't understand. Rodale Books; 2018.

- For a full exploration of that topic, see my article about fibromyalgia.