Do Nerve Blocks Work for Neck Pain and Low Back Pain?

Analysis of the science of the “block & burn” therapies, stopping the pain of facet joint syndrome with nerve blocks, joint injections, and nerve ablation

Finding the source of any kind of stubborn pain is tricky, because there are so many potential causes, many of which have no objective signs — or none that can spotted easily. However, explaining neck and low back pain is a particularly tricky clinical challenge. Therapists and doctors should rarely diagnose the specific source of neck and back pain with high confidence — there are too many possibilities, and too many of them are poorly understood.

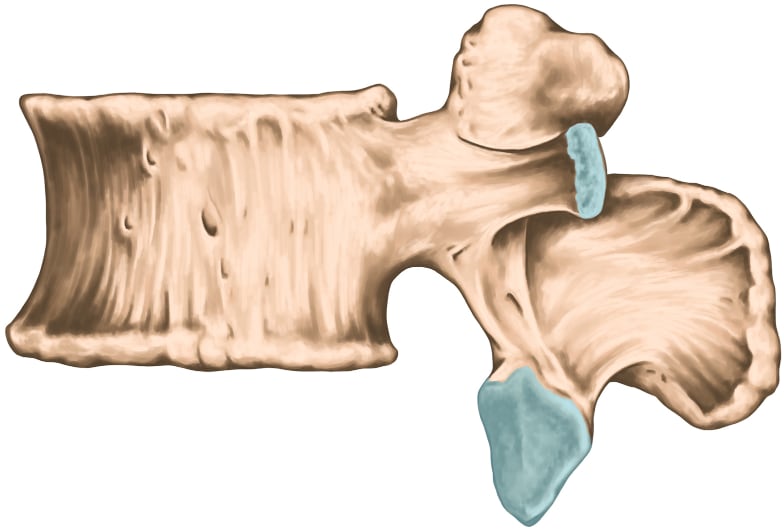

One possible source of pain, and a common suspect, is the knuckle-like facet joints. You have a pair of facet joints for each vertebra. These are the joints that pop in many people as you twist and flex your spine. Each facet joint moves only a little, sliding on dime-sized cartilaginous surfaces. There are many possible ways that facet joints may cause pain, and a certain amount of facet joint pain is probably a factor in many cases of spinal pain. If facet joints are hurting, we call it “facet joint syndrome.”

A lumbar vertebra. The larger blue cartilaginous area at the bottom is the surface of a facet joint, which connects to a corresponding joint surface projecting upwards from the vertebra below. (The other blue area is a costovertebral joint.)

In a sense it doesn’t even matter what, exactly, might be going wrong with a facet joint — not if you can numb the whole thing, turning off all sensation like flicking a light switch. Facet joints are specific anatomical structures with clear “edges,” much clearer than other tissues like muscle,1 so they have become the target of several minimally invasive diagnostic and treatment procedures that aim to temporarily or permanently silence any pain noise coming from them (part of “interventional pain management” formally, or “block and burn” informally):

- injections of various pain-relieving substances into the joint itself

- nerve blocks which temporarily cut off sensation in the whole structure

- destroying those same nerves (denervation, usually achieved with heat generated by a medium frequency alternating current, AKA “radiofrequency ablation”)

Note that everything here applies strongly to sacroiliac joint pain as well.

These procedures are all provided by medical specialists, most likely either a physiatrist or an orthopedic surgeon. Do they work? Are they safe?

EXCERPT This article is an excerpt from very detailed tutorials about neck pain and back pain.

Nerve blocks as a diagnostic tool

Here’s an interesting (if somewhat drastic) way to find out if a facet joint is the wellspring of spinal pain: cut off the nerve supply to the facet joint! If your pain stops, voila: presumably that’s where the pain was coming from.

This is called a “medial branch block” (MBB), or just “nerve block.” The medial branch nerves are the wee nerves that send information to the brain about tissue condition in the facet joints.2 Without those nerves, the facet joint reports nothing to the brain, and so the brain assumes all is well — a nearly perfect numbing. It’s much like getting part of your mouth “frozen” at the dentist.

Thus, if an MBB relieves pain, “well there’s your problem.” That provides some diagnostic confidence that the facet joint is the cause of the pain.

But … it’s not exactly foolproof. This practice is supported as a diagnostic tool only by scanty, conflicting scientific evidence. Some authors call it “fair” evidence, for the neck joints, but probably shouldn’t have.3 The evidence is similar for the thoracic4 and lumbar5 spine.

Nerve blocks as a flawed diagnostic tool

Many other factors tend to confuse this method of diagnosis, which is probably why it hasn’t been validated by research. For example:

- What if 60% of your pain is coming from one facet joint, 20% from another, and 10% from a third? And only one of them gets blocked? What if something else entirely is also causing pain?

- What if the injection just misses? It can be difficult to be accurate with these injections. It takes skill!

- What if the anaesthetic “leaks” into surrounding tissues and numbs the wrong thing?

It gets murkier: the amount of relief low back pain patients get from facet joint injections can be predicted by psychological factors.6 Why would that be? Numbing might provide strong enough temporary relief to create an overconfident “eureka!”

And that confidence might itself deliver some pain relief (or reduced suffering), further clouding the issue, and adding up to a false positive: a misleading result that puts a spotlight on the facet joint that is actually innocent, or only part of the problem.

This kind of confusion maybe be rare, and clear relief probably might mean what it seems to mean. But we just don’t really know.

All this complexity is also why “the effectiveness of a specific treatment cannot simply be reverse engineered to conclude what caused the pain.”7 So MBB results should be considered as a diagnostic tool for stubborn neck or back pain, but nothing is ever as simple as it seems.

Nerve blocks as treatment

Nerve blocking might be diagnostic — maybe — but can it be therapeutic?

The evidence for treatment efficacy is mixed — of course! Results are far from guaranteed, about two kilometres from it. Benefits may be temporary and/or partial, and it’s not risk-free. The value of injections right into the joint is particularly questionable. A treatment does not have to be perfect to be worthwhile, and there is probably some good being done with these procedures, but not a lot, or the evidence wouldn’t be so thin.

The journal Pain Physician has published a few studies of facet joint injection treatments for the cervical and lumbar spine,89 and the thoracic spine.10 The only major review was published by Spine,11 which was the most discouraging: “There is insufficient evidence to support the use of injection therapy in subacute and chronic low-back pain,” although the benefits of some types of injection therapy for certain patients “cannot be ruled out.” The others were more positive, but also not based on much actual data. So what do the more specific reviews in Pain Physician have to say?

Much of what’s positive in them comes from a 2008 experiment (done by some of the same researchers), in which they gave medial branch nerve blocks to 120 chronic neck pain patients, and found that they produced “significant relief and functional improvement” in “over 83% of patients.”12

This study has been widely cited as near proof that nerve blocks work, and it is the main source of enthusiasm about needles for neck pain in recent history. I think it is pretty decent evidence, and so MBB is an option chronic neck or back pain patients could consider. However, as always, you have to read the fine print. A more detailed look at this paper is quite educational …

6 reasons to curb your enthusiasm for medial branch blocks as a treatment option

I can see at least 6 reasons why the Manchikanti et al. paper is not exactly a slam dunk, and MBBs are no miracle cure:

- “Over 83%” of patients sounds awfully good — and it is, for a neck or back pain treatment — but it’s hardly everyone. More than 1 in 10 people were not helped, even after a facet joint was “confirmed” as the source of pain by an earlier nerve block.

- In science, the words “significant improvement” do not mean “cured”: they mean statistically significant. Statistical significance just doesn’t mean much; the concept is routinely abused to make study results seem better than they are. Those who were helped were not necessarily helped a lot — just enough that we can say, “Yep, that treatment was better than nothing.” So many of those people almost undoubtedly had results that were somewhat less than miraculous.

- These patients didn’t just get one needle in the neck and then walk out the door with their “significant improvement.” They walked out the door … and then came back again a few weeks later for another dose. And another. The average number of treatments over the course of the year they were studied was, wait for it … three and a half, plus or minus one. That’s off to the pain clinic with you three, maybe even four or five times per year to get your “significant results.” That’s a fair amount of getting stabbed in the neck, I have to say. Is this procedure starting to sound a little less awesome than it did at first?

- As implied by the need for repeat treatments, the benefits were not exactly long term. The average duration of average pain relief was 14–16 weeks, give or take a lot. Some patients were getting their statistically significant but probably minor symptom relief for only half that time — about a couple of months. No wonder they needed repeat treatments.

- And, of course, it’s a minimally invasive procedure, and all invasive procedures have higher costs and risks, and should be avoided unless absolutely necessary.

- Last and definitely not least, these patients were not compared to patients receiving any other kind of treatment or no-treatment or a placebo, which I find really strange. It leaves us wondering how well they would have done with no treatment at all. Spinal pain is notoriously unpredictable. People who receive no treatment routinely experience “significant relief” for no apparent reason. Thus, this study just doesn’t fully answer the question it asks — it can’t.

And that’s the most “promising” evidence!

Kill it with fire! Ablation

“I say we take off & nuke the entire site from orbit. It’s the only way to be sure.”

Another related way to treat pain is to destroy the nerves that detect possible tissue threats (nociceptors). If you can’t numb it … nuke it!

It’s silly hyperbole to call it “the nuclear option,” but there is something quite violent about destroying nerves with heat, the active ingredient. Specifically, this is achieved with electrocoagulation or radiofrequency ablation (and other names and similar methods). A tiny probe delivers delivers a medium frequency alternating current (“radio frequency”) to the tissues, which generates enough heat to the destroy the tissue at the tip of the probe. Think of it as a cousin of microwaving your lunch. It’s a precise way of "burninating" things.

In the case of treating spinal pain, it’s usually the nerves to the facet joints or intervertebral discs that are targeted.

This treatment approach might seem simplistic and destructive and maybe even a Very Bad Idea … and you could be right. It’s understudied, like practically everything in this business, but it has produced some seemingly promising results for wrist pain, back pain, and tennis elbow.13 This “circumstantial evidence” is better than nothing. Maybe.

And on the other hand …

So what could possibly go wrong with denervation?

It definitely doesn’t always work, of course. An important 2017 review in the Journal of the American Medical Association was quite negative: “The findings do not support the use of radiofrequency denervation [for back pain].”14 Which is a little surprising. Why wouldn’t destruction of nerve fibres completely, definitely solve the problem? The caveats are very similar to those for blocking nerves, but it’s worth being redundant:

- Most importantly, the destruction might not be complete: the surgery might not destroy enough of the right nerves. There’s a fallible human handling that little tiny magic wand!

- Pain doesn’t actually come from nerves: they merely deliver information about tissue condition to the brain for consideration. The brain has other ways of deciding whether or not a neck hurts, and it can simply ignore the eerie silence of destroyed neck nerves. If the brain thinks your neck hurts … then your neck hurts. (Remember the phenomenon of phantom limb pain: if people can feel missing limbs, they can certainly feel partially denervated joints!)

- The procedure might seem to work at first due to the powerful placebo effects that surgery can generate, only to reassert itself later.15

- Spinal pain has many possible mechanisms. Depending on exactly what’s going on, denervating facet joints could just be a clean miss.

So should you ablate? Like so many uncertain treatments with risks, it might be worth a try for desperate patients only after plenty of other options have been exhausted. It’s most likely to work at least a bit if there is a strong clinical suspicion of facet joint pain specifically, as opposed to other sources. But the evidence is too limited and mixed for any real confidence.

I will return to the most recent evidence to wrap up, after looking at one more type of related therapy …

Epidural injections

Epidural injections are a similar-but-different needling treatment in the interventional pain management category, and they are “one of the commonly performed interventions in the United States.” Unlike blocking and burning, these injections are not directed at specific facet joints. Instead, you just squirt a dose of anaesthetic into the space alongside the spine that is inhabited by the spinal nerve roots.16

The further up the spine, the smaller the epidural space gets, and the more difficult and risky it is to stick a needle into it. Because of this, epidural injection techniques have long been more common and more suitable in locations from the upper back down, and their reliability and safety for neck pain has been considered dubious even by its proponents. However, it is becoming more accurate, practical, and safe in the neck with new techniques. Fluoroscopic guidance! Ask your surgeon if he’s using it — and, if not, why not.

So, here’s a shocker: “The underlying mechanism of action of epidurally administered steroid and local anesthetic injection is still not well understood.”17 And yet, despite the predictable mysteriousness of it, there is some evidence that it’s helpful. In early 2009, Benyamin et al. concluded that studies of epidural injections show “that they have a significant effect in relieving chronic intractable pain of cervical origin and also provide long-term relief.”18

And there’s that damned misleading word again: “significant”! Meaning statistically significant, not necessarily clinically significant.

Block and burn bites the dust in a big 2025 review … and doctors bluster!

I’ve saved the worst news for last, because it applies to all of the treatments discussed above — all the “interventional pain medicine” stuff, for all chronic spinal pain, from occiput to sacrum. This 2025 evidence update is likely to be the last major word on the topic for some time.

A BMJ guideline paper,19 based on a big meta-analysis by Wang et al.,20 and it has been a hot item on social media. (Very hype! Such viral!) The clinical guideline paper has a good infographic. And the guideline’s bottom line …

“Well-informed people would likely not want such interventions.”

Many doctors were not amused! Quelle surprise. Thirty-four medical professional societies (!) got together to demand retraction, which catapulted this science news to the top of my priority list, because Wow! That’s a lot of medical societies! They all have “serious concerns” about how those cranky conclusions were reached, and demanding “retraction” certainly makes their concerns sound Very Serious Indeed.

Okay, so, they have concerns. What they do not appear to have is … evidence supporting their profitable practices.

The concerned doctors mainly cite their clinical experience, and their personal opinions of the evidence (there are always positive trials to cherry pick, of course, and they do). But the whole point of this meta-analysis was to evaluate the evidence more rigorously than that! And so the objectors — no matter how big and fancy the choir, no matter how haughtily they can Harrumph! — mostly come off like they’re fighting the progress of evidence-based medicine. Sour grapes from the people who make their living selling these treatments (always with earnest good intentions, no doubt).

The three most dangerous words in medicine: in my experience.

Mark Crislip, MD

It’s an old story — one which strongly fits the pattern of surgery’s lateness to the EBM party (see Surgery: The ultimate placebo). And the guideline authors had a polite but firm response to all this:

“If some clinicians believe that they can correctly identify patients with chronic spine pain who will benefit from interventional procedures, we believe they should undertake high quality sham-controlled trials to provide evidence. As we note in our guideline, such evidence would alter our recommendations.”

I have less diplomatic translation.21 (That’s a fun footnote.)

Reasonable people can disagree (but they can’t call for retraction)

There are reasonable arguments for the judicious use of blocking and burning, with informed consent, despite significant “evidence of absence.” Even the strongest evidence is never the whole story … and this evidence, while thoroughly discouraging, is not the strongest we can imagine … and there is some absence of evidence going on here too: more study is still needed, because what we have is neither uniformly negative nor of good enough quality.

Yes, actually, there is a chance … just not a very good one. I think of this meme every time I see healthcare pros objecting to evidence that their treatments don’t work, looking for ANY way to avoid the bad news. Finally got around to using it for this story, a particularly perfect fit.

For instance, the evidence on radiofrequency ablation — arguably the most important member of this category — is rated by Wang et al. as “very low certainty.” We can and should do better. It’s unlikely that better trials will bring better news — it usually goes exactly the other direction — but they might. There is a chance that there is still something worthwhile in interventional pain management, and the best doctors might even be better at finding it.

But none of those reasonable responses justify calling for the retraction of papers that report on the evidence we have so far.

About Paul Ingraham

I am a science writer in Vancouver, Canada. I was a Registered Massage Therapist for a decade and the assistant editor of ScienceBasedMedicine.org for several years. I’ve had many injuries as a runner and ultimate player, and I’ve been a chronic pain patient myself since 2015. Full bio. See you on Facebook or Twitter., or subscribe:

What’s new in this article?

Apr 24, 2025 — Major science update (and it’s not good news).

2017 — New section: “Kill it with fire! Ablation.”

2017 — More detailed discussion of treatments. New section, “Epidural injections.”

2017 — Change in position. After reviewing the same scientific papers previously cited more carefully, I decided that they were much less promising than I originally thought. The article has flip-flopped from optimism to pessimism about nerve blocks without a single change in what’s actually cited, just a change in the level of diligence in interpreting the science.

2017 — Science update, additional references supporting the diagnostic utility of medial branch blocks, and an additional caveat about how they can fail.

2010 — Updated with reference to Thackeray.

2009 — Publication.

Notes

- Where is muscle pain? Compared to facet joints, the anatomical location of the source of muscle pain is like trying to find a smoke signal in the fog. We aren’t even sure if there is such a thing as a discrete painful lesion in muscle (other than bruises). Even if there is, they aren’t easy to reliably locate.

- Let me explain “wee little nerves” with a bit more jargon for my professional readers: the nerves in question here are the medial branches of the dorsal ramus nerves that innervate the facet joints.

- Falco FJE, Manchikanti L, Datta S, et al. Systematic review of the therapeutic effectiveness of cervical facet joint interventions: an update. Pain Physician. 2012;15(6):E839–68. PubMed 23159978 ❐

This small 2012 review concluded that the “evidence for cervical medial branch blocks is fair.” Unfortunately, “fair” is a ridiculous word to use when summing up a “body” of evidence based on one trial (no matter how good) and one prospective evaluation. They also granted “fair” evidence for radiofrequency neurotomy based on just one randomized controlled trial (and a few almost meaningless observational studies).

Evidence for two other cervical joint interventions was “limited” by comparison! Indeed.

In my opinion, they did not find enough of any kind of evidence about anything to draw any conclusions whatsoever.

This paper is very similar to Manchikanti et al., regarding the thoracic spine (again involving some of the same researchers).

- Atluri S, Datta S, Falco FJE, Lee M. Systematic review of diagnostic utility and therapeutic effectiveness of thoracic facet joint interventions. Pain Physician. 2008;11(5):611–29. PubMed 18850026 ❐

A review of barely adequate scientific literature on thoracic spinal joint interventions, but some of what they found was promising: good (Level I or II-1) for both diagnostic and therapeutic nerve blocks. But the number of papers on this topic really is extremely small: even years later, Manchikanti 2012 only reviewed a handful. The optimistic conclusion here is not resting on much.

- Datta S, Lee M, Falco FJE, Bryce DA, Hayek SM. Systematic assessment of diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic utility of lumbar facet joint interventions. Pain Physician. 2009;12(2):437–60. PubMed 19305489 ❐

This review of diagnosis and treatment of lumbar facet joints found very little, a “paucity of published literature,” but what they did find seemed to be positive: good evidence for diagnostic nerve blocks, and fair when using them for treatment. Notably, Staal concluded that the literature was too scanty to conclude anything.

- Wasan AD, Jamison RN, Pham L, et al. Psychopathology predicts the outcome of medial branch blocks with corticosteroid for chronic axial low back or cervical pain: a prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:22. PubMed 19220916 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 55303 ❐ “Psychiatric comorbidity is associated with diminished pain relief after a MBB injection performed with steroid at one-month follow-up.”

- Ben Cormack, Peter Stilwell, Sabrina Coninx, Jo Gibson. The biopsychosocial model is lost in translation: from misrepresentation to an enactive modernization. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2022:1–16. PubMed 35645164 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 52047 ❐

- Datta 2009, op. cit.

- Atluri 2008, op. cit.

- Manchikanti KN, Atluri S, Singh V, et al. An update of evaluation of therapeutic thoracic facet joint interventions. Pain Physician. 2012;15(4):E463–81. PubMed 22828694 ❐

This tiny review was based on extremely limited evidence: just four studies (three non-randomized), and “The only positive studies were of medial branch blocks performed by the same group of authors” (e.g. Manchikanti 2008) … who also happen to be the authors of this review. That doesn’t mean they are wrong, of course, but it’s an important caveat. The word they chose to describe this level of evidence was “fair.” I’m not sure that’s fair! They are mostly just re-reporting the positive results of their own trials.

They also concluded there wasn’t enough evidence about intraarticular injections and radiofrequency neurotomy. They probably should have concluded the same about medial branch blocks!

This paper is very similar to Falco et al., regarding the cervical spine (again involving some of the same researchers).

- Staal JB, de Bie RA, de Vet HCW, Hildebrandt J, Nelemans P. Injection therapy for subacute and chronic low back pain: an updated Cochrane review. Spine. 2009 Jan;34(1):49–59. PubMed 19127161 ❐

A review of all kinds of injection therapies for the low back and finding “no strong evidence for or against the use of any type of injection therapy,” which is not as optimistic as Datta 2009.

- Manchikanti L, Singh V, Falco FJE, Cash KM, Fellows B. Cervical medial branch blocks for chronic cervical facet joint pain: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial with one-year follow-up. Spine. 2008 Aug;33(17):1813–20. PubMed 18670333 ❐

- See Romero 2015, Berry 2011, Rose 2013 and Storey 2011.

- Juch JNS, Maas ET, Ostelo RWJ, et al. Effect of Radiofrequency Denervation on Pain Intensity Among Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain: The Mint Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA. 2017 Jul;318(1):68–81. PubMed 28672319 ❐

Radiofrequency denervation is a common but unproven way of treating back pain by destroying nerves. This credible paper reports unambiguously negative results of three similar, good quality trials with more than 600 subjects, each one focusing on a particular type of stubborn back pain. Treatment “resulted in either no improvement or no clinically important improvement.” This is completely consistent with a strong theme in musculoskeletal medicine: surgery does not help chronic pain (Louw).

- Not many surgical procedures have ever been properly compared to placebo, and the few that have been often fare poorly. I’ve already referred to Moseley 2002 and similar studies a couple of times. See also Louw for several examples of musculoskeletal surgeries that weren’t better than placebo, or Surgery: The ultimate placebo: an entire book full of examples.

- Epidural means “around the dura.” This is different than the even deeper injection of anaesthetic into the fluid around the spinal cord itself.

- Seems obvious, right? You’re bathing a nerve root in anaesthetic! That’s got to be pain relieving! But neurology and pain aren’t simple, and it’s not clear that anaesthetizing the nerve root is necessarily going to have the desired effect.

- Benyamin RM, Singh V, Parr AT, et al. Systematic review of the effectiveness of cervical epidurals in the management of chronic neck pain. Pain Physician. 2009;12(1):137–57. PubMed 19165300 ❐

- Busse JW, Genevay S, Agarwal A, et al. Commonly used interventional procedures for non-cancer chronic spine pain: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2025 Feb;388:e079970. PubMed 39971339 ❐

- Wang X, Martin G, Sadeghirad B, et al. Common interventional procedures for chronic non-cancer spine pain: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2025 Feb;388:e079971. PubMed 39971346 ❐

This review of the common "block and burn" treatments for neck and back pain was resoundingly bad news. All of the treatments studied were either radiofrequency ablation of nerves (“kill it with fire”) or some combination of injections of steroids or anaesthetics into muscles, joints, or epidural space. The abstract is a bit of a tangled mess of similar results for similar treatments, so I’ve tidied it up a bit for readability, and sorted roughly in order of descending certainty:

“Probably provide little to no difference in pain relief”:

- epidural injection of local anaesthetic and steroids

- radiofrequency ablation of dorsal root ganglion

“Little to no difference in pain relief (moderate certainty evidence)”:

- epidural injection of local anaesthetic

- epidural injection of local anaesthetic and steroids

“May provide little to no difference in pain relief (low certainty evidence)”:

- intramuscular injection of local anaesthetic

- epidural steroid injection

- joint-targeted injection of local anaesthetic

- joint-targeted injection of local anaesthetic with steroids

- epidural injection of local anaesthetic or steroids

“May increase pain (low certainty evidence)”:

- intramuscular injection of local anaesthetic with steroids may increase pain

“Very low certainty” evidence one way or the other:

- facet joint radiofrequency ablation

It’s amazing that ablation hasn’t been studied well enough to get a clearer result. This is one of those moments when I wonder if evidence-based medicine is ever going to get its shit together.

So that’s a mixture of decent evidence-of-absence and murky but suspicious absence-of-evidence. As always, when a lot of weak and likely biased evidence fails to produce a clear positive signal, it’s extremely unlikely that strong and unbiased research will be an improvement.

My less diplomatic translation of the response to the call for retraction:

“Nice try, but that’s not how this works. You’re all kidding yourselves if you think you can reliably identify the ‘right’ patients to use these treatments on, even assuming that they exist. But if they do and you actually can, then put on your big boy pants and try science, because you shouldn’t have any trouble proving your point under properly controlled conditions, now should you? Or does your voodoo break when there’s a statistician nearby? Wake us up when you’ve got actual evidence.”