Kneecap replacement: how bad an idea is it?

This is an excerpt, somewhat pruned, from a major update to my book about patellofemoral joint pain — kneecap pain, that is (and unexplained pain on the front of the knee more generally). I neglected this subject for years, because it’s rarely prescribed and mostly not a great idea. But a lot of readers have heard about it and wondered about it, and so it’s high time I provided some food for thought on the topic.

But this is not just for the knee pain folks!

I hope this is a good example of how to think about any orthopaedic surgery. For instance, it features a little snarky reaction to Elon Musk’s cringe-inducing recent tweet about spinal surgery — because what was wrong there applies to most “carpentry” surgeries, and I could include it in the main surgery chapter of all of my books, and I probably will.

TLDR: There’s not much of “the good” to report about patellofemoral joint replacement; it’s mostly just the bad and the ugly.

The patellofemoral joint is only one part of the much larger and more complicated knee joint, so “replacing” it a much smaller operation than a total knee replacement. The incision is way smaller, and all the ligaments are left intact, so the risk of complications is lower. The goal is to “resurface” the end of the femur where it contacts the back of the kneecap: that is, cut away the cartilage and bone and install a metal part in their place. This tends to be a more durable implant.

But just because patellofemoral joint replacement is tame relative to replacing other parts of the knee doesn’t means it’s a good idea.

One reader reported that his surgeon says it is “never done” and would be “considered malpractice”! That is probably overstating a little, but perhaps only a little. Certainly the procedure is performed, but my understanding is that it’s rare. I doubt it should be considered “malpractice” in every case, but perhaps most of them. And that’s probably what that surgeon meant: it’s so rarely a good idea that odds are that it’s medically irresponsible in most cases where it’s recommended or performed.

But it is, of course, defended by some professionals! And they might not even be wrong.

Musk on surgery 🙄

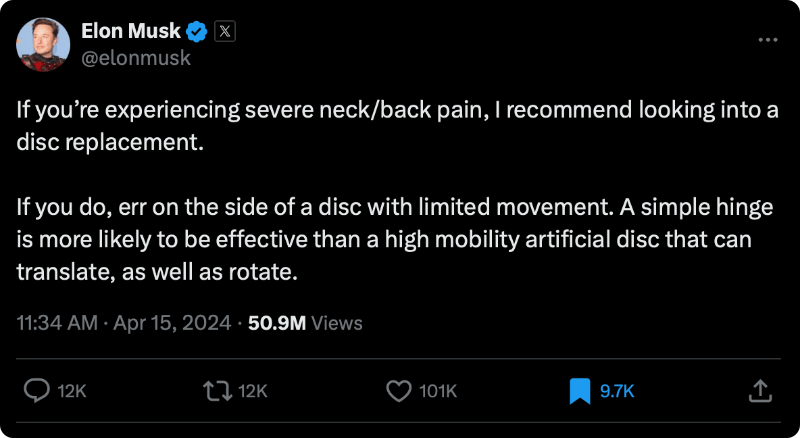

The main appeal of any joint replacement — arthoplasty, or “joint molding” — is the idea that you are replacing the “bad parts” with nice, sturdy titanium. This has a simplistic appeal to us, which was vividly promoted Elon Musk in early 2024:

Really bad, shallow advice. Fifty. Million. Views. Fifty million!

Omagerd, such an engineer thing to say! 🤦🏻♂️ You’re way out of your lane there, Musky! Hell, sir, you cannot even see your lane from there.

There were many exasperated and irate reactions from experts — hundreds? thousands? — but I never saw one that emphasized the most basic error: that hopelessly naive assumption that a nice metal part is better than biology. Simplistic structuralism at it’s finest!

And how many people were exposed to this wisdom? 51 million and counting after just a couple weeks. Mind-boggling. Depressing.

Are you even replacing the right thing?

The main problem with patellofemoral joint replacement is that it’s not clear that it’s even aimed at the actual problem. While it might seem like you are replacing the parts that hurt … that's not at all certain. No one can guarantee replacement of all the parts that are actually driving the pain. Even total knee replacements don’t replace all the knee’s tisses. In fact, many parts are left intact even in a “total” knee replacement... and some of them can absolutely hurt. But it’s more complicated even than that!

Nor even does “eliminating” actual sources of pain doesn’t guarantee success. Consider phantom limb syndrome, where the pain carries on despite the complete absence of a limb … because the brain continues to get nociceptive signals from the disturbed nerves in the stump (see Ilfeld). Which the brain dutifully assumes must have come from the limb that is no longer there! So much for getting rid of the source of pain — it just moves! It just keeps on coming from the edge of the injury. “Foiled again.” Which is how it often goes with pain.

But that is just one of the reasons why we see so much serious post-surgical pain.

It’s always more about the physiology than the biomechanics

The bigger reason for caution is just that surgery isn’t “tidy” and the body often struggles to recover. Consider how old injuries can hurt many years later, despite being apparently healed.

More sinister: the body may well struggle to recover from the surgical insult for the same reasons there was problem in the first place. That is, the same physiological vulnerability that resulted in developing the pain originally, and/or which made it severe and stubborn enough to become the kind of problem that makes you desperate enough for surgery … is the same physiological vulnerability that will make it hard to bounce back from that surgery.

For instance, it’s plausible that even minor surgeries might trigger a disproportionate and stubborn inflammatory response in some people — which could actually accelerate arthritic degeneration of whatever tissue remains. In other words, you could basically just adding more trauma to the equation, making a bad situation worse.

I am well aware that a citation is needed for that statement, and I’ve looked for one and failed. But I’m not surprised, because it’s not an easy thing to study … and this is in a field where even the most obviously needed and simple tests of efficacy still haven’t been done.

Which brings us to our next problem.

Not much science on this (or any orthopedic surgery)

Surprisingly, many orthopedic surgeries have never been tested properly, and it hasn’t gone well for many of those that have, demonstrating that much of the apparent benefit of those surgeries was always due to placebo (Louw et al). Although there’s plenty of research on knee replacement, almost none of it is the kind that we actually need to determine how well it actually works: that is, controlled trials. There’s just one trial that gets us halfway there! Just a single comparison of surgery to doing nothing (not a sham, which is why it only gets us halfway). Skou et al reported in 2015 that TKR got clearly better results, but it also had a lot more complications. That’s roughly a tie between the pros and the cons, which is not an encouraging outcome for people considering that more conventional surgery.

But my point here is not whether tibiofemoral replacement is effective, but just that we really still can’t know … because it has barely been studied. So it’s not surprising that a citation is still needed for anything more obscure, such as patellofemoral joint replacement. And it will probably still be needed in a decade.

Meanwhile, we know this much:

- Patellofemoral joint replacement is rare because it is widely considered a bit sketchy, even by orthopedic surgeons — a profession not exactly known for their restraint. 😜

- It’s doubtful that kneecap replacement can address the actual problem in many cases.

- Even when surgeries are much more clearly justified, they still have significant rates of complications and failures … and often quite possibly for the same biological reasons that made the problem serious enough to consider surgery in the first place!