Bone on Bone

How often are those dirty words about arthritis a harmful exaggeration? And should we ever use them, even when it’s accurate?

Is “bone on bone” a bad thing to tell patients? Is BOB a “nocebo”? That’s the opposite of a placebo — something that harms with fear, uncertainty, and doubt. More precisely: a nocebo is a grief rather than relief from belief — a poor health outcome from psychological mechanisms, mainly pessimistic expectations of treatment or prognosis.

So, can just saying BOB make things worse for arthritis patients? Do healthcare professionals even have that kind of power over patients? They do! Although not necessarily in a spooky mind-over-body way.

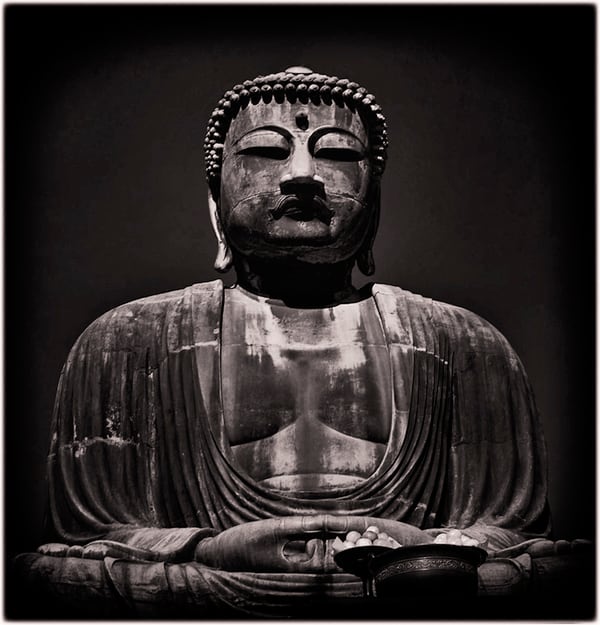

I have collected many collecting surprising examples of the discouraging and alarming things healthcare providers tell patients, and “bone on bone” is the most controversial one so far. Some people suggest that the truth cannot be nocebic, and sometimes BOB is true. But is truth really enough? There is a Buddhist tenet that before speaking you should ask yourself…

- Is it true?

- Is it helpful?

- Is it kind?1

This article is a deep dive into this notorious choice of words. Is it truly nocebic? Can it be true and nocebic? I tackle the problem in two parts:

- Part one addresses the question: how often is it actually true?

- Part two (for members only) moves on to examine the arguments for and against using the words “bone on bone” with patients, even when it is true.

•

Part I: How often is “bone on bone” bogus?

Bares bones touching bare bones

To start, let’s look at exactly what “bone on bone” means, and — in the absence of ideal data — how we can know how often this melodramatic pseudo-diagnosis is actually accurate.

“Bone on bone” can indeed be a bona fide accurate description. Sometimes severe cases of arthritis really do result in the loss of most or all cartilage, and BOB is literally true, not even an exaggeration. Cartilage can in fact go away. Naked joint surfaces can slide on each other.

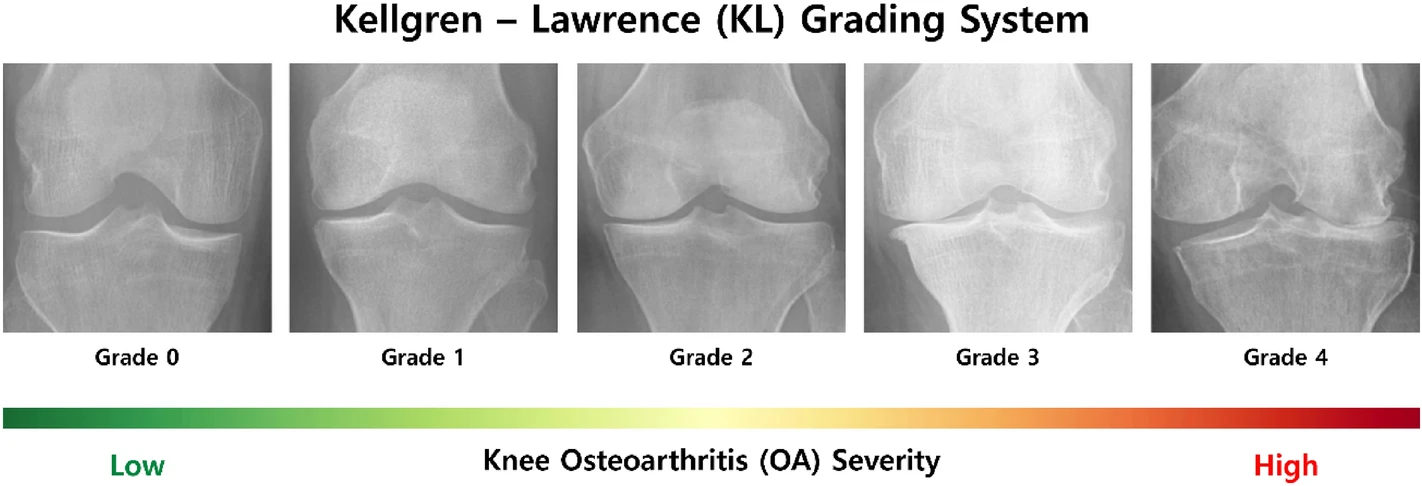

There are various grading/scoring systems for osteoarthritis, and they all have a “worst” tier that shows things like “marked narrowing of joint space, severe sclerosis [scarring, hardening of tissues], and definite deformity of bone ends.” The Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) system is probably the most common.

Knee joint X-rays for each KL grade according to OA severity. The KL grade system categorizes grades according to two aspects of OA: the extent of joint space narrowing, and the size of osteophytes (spurs). From Ensemble deep-learning networks for automated osteoarthritis grading in knee X-ray images, by Pi et al., CC BY 4.0.

Weirdly, cartilage may be a little more optional than we think, because not all of this severe osteoarthritis is painful, or not very. This is partly because the sclerosis can probably be effective, much like calluses on hard-working fingers. It’s also probably a function of complex metabolism and neurology, with some people being much less likely to hurt in exactly the same structural circumstances that are agonizing for others.

So wouldn’t it be tragic if “bone on bone” scared such a patient who’s actually mostly fine? More pain, and unnecessary surgery? If “imaging is not needed to diagnose osteoarthritis”2 — because it’s actually just pain and disability that matter, not the tissue state — then do we really need to say what the joint looks like? Why bother, when it’s apt to make their symptoms worse, or discourage exercise?

It’s important to consider the possibility that those words should never be said even to patients who actually do have severe osteoarthritis. Is it kind or helpful to describe these cases in that way? More about that in part 2. For now I just want to make it clear that the factual accuracy of BOB is not the only consideration here.

Sometimes, however, BOB is not even true. We need to consider that first.

“Bone on bone” also isn’t always accurate

How often do professionals exaggerate the severity of osteoarthritis by invoking “bone on bone” when it isn’t actually true? Or not nearly true enough for those dramatic words?

Unfortunately, we don’t know the “exaggeration rate” without some research that will probably never happen. But we can make an educated guess based on some clues:

- There’s plenty of expert and patient opinion about this.

- Not all BOB is created equal, so it can obviously be technically true without being true in spirit.

- Osteoarthritis grading is known to be error-prone and imperfect, and therefore vulnerable to bias and “spin.”

- There’s a clear profit-motive for exaggerating, and we know that many orthopaedic surgeries are over-prescribed and so likelier to be sold by inflating the need.

And now in more detail…

The anecdotal and soft evidence that BOB is overstated

- It’s a common clinical impression that BOB is often an exaggeration. “It happens far too often,” writes Dr. Howard Luks, an orthopedic surgeon, responding directly to my question about this. “If I had a dollar for every time an orthopedist told a patient it was the worst knee OA they ever saw I would be rich,” writes Jeffrey Fusilier, Doctor of Physical Therapy. (Of course, cynicism can also be exaggerated! But these clinical suspicions probably reflect at least some truth.)

- Patients often report that they have been told they were BOB only to substantially recover. An example I know well: my father. He refused surgery despite occasional episodes of severe pain. Since then, with regular exercise and some help from canes and scooters, his knees have been better — flare-ups are now rarer and milder! His original x-rays from don’t look like KL 4 knees to me: either he was not very BOB in the first place, or he adapted to it better than most people think is possible, or a little of both.

- The sheer variety of obviously nocebic statements of all kinds reported by patients is damning. It’s clear that melodramatic clinical communication happens. Exaggeration is something humans do quite a bit of for many reasons!

- Bunzli et al. reported that all of the 27 people in their study of beliefs about knee osteoarthritis were sure that their knee pain was “bone on bone,”3 which shows at least that it’s a near-universal mental image (in people headed for joint replacement). Most of that belief probably came from doctors, and it’s unlikely to be equally true in all cases. The more universal the idea, the more it probably differs from messy reality.

- We tend to talk about BOB like it’s all or nothing, but the cartilage might be gone only in a tiny spot, rather than a large area, like the difference between a little bald spot on the top of your head versus Vin Diesel bald. This is the main mechanism by which BOB can be an exaggeration without actually being a “lie”: that is, it can be technically true, but just not in the same league as the next patient. Surely formal, expert grading systems take care of all this? Um, about that…

Surgery isn’t always a bad option, but surgeons and patients alike reach for it too readily. “Pigs oink and surgeons cut!” The words “bone on bone” seem finely tuned to emphasize the putative necessity of surgery, and to teach patients to fear the very thing that we most need, even with severe osteoarthritis: exercise.

Harder evidence that BOB is often overstated

- Osteoarthritis grading is as much art as science. It “depends on the clinician’s subjective assessment” and the accuracy of that assessment “varies significantly depending on the clinician’s experience and can be particularly low”.4 A 2018 study showed lousy agreement between clinicians about the same images: “None of the studied OA grading scales showed acceptable reliability. The evaluation of patients with OA should not be dependent on radiographic findings alone; clinical findings should also guide the treatment and follow-up”.5

- Extremes are easier though, right? 100% of people would agree that Vin Diesel is bald, because he’s super bald. So surely arthritis grading is more reliable with severe osteoarthritis? Yes, but still well short of perfect. Klara et al. showed that even lowly medical students could usually see the same knee nastiness as an experienced surgeon. But not always.6

- Other joints are much harder to grade than knees. For instance, KL grading “is not applicable to the subtalar joint”.7

- If we “follow the money,” it’s obvious that there’s a profit motive for exaggeration. One of the best ways to sell treatments is to dramatize the seriousness of the need, to warn people. Many medical warnings are justified, of course — but the unjustified ones benefit from that legitimacy. Clinicians can easily rationalize getting overzealous with their warnings (“better safe than sorry”). And so it’s likelier that moderately severe arthritis probably gets “rounded up” to BOB. It’s probably just a matter of time before it becomes true, amiright? Or patients are “frankly” told that BOB is inevitable.

- Speaking of profitable procedures: surgeries for arthritis are definitely over-prescribed, particularly in the United States, where they are most likely to be profit-motivated. And if you’re recommending too many surgeries, you’re probably also trying to justify them… and a bit of BOB hyperbole is a handy way to do it. But is there good evidence of over-prescription? Whether surgery is “over” prescribed is relative to how much it should be prescribed, which is a squishy comparison! However, when good clinical trial evidence clearly shows that a procedure just doesn’t work, or not very well, and probably should only be prescribed quite rarely if it all, then we should see the industry respond by doing much less of that procedure — and if it doesn’t, that constitutes strong, direct evidence of over-prescription. And we do indeed see that kind of evidence for all arthroscopic procedures in general, because they are virtually all “disproven” for arthritis for years now.8 Persistently high rates of prescription are especially clear for meniscectomy,9 debridement,10 and “knee lube” injections (viscosupplementation).11 The most important surgical prescription for BOB is knee replacement, and we lack evidence of that kind for that specific procedure. That is probably just a matter of time, however …

- It’s much harder to know if a treatment is over-prescribed when we know that it is truly helpful for many patients, and that is probably the case for replacements. However — and this is subtle but important — many orthopaedic surgeries have never really been tested properly … and there’s a very strong pattern of such surgeries failing good clinical trials when they are finally conducted.12 Knee replacements do not actually rest on a foundation of controlled clinical trials, and the only major partially controlled trial to date, in 2015, was a mix of good and bad news.13 It’s a safe bet that proper testing of replacement, when it finally happens, will produce at least some bad news, showing that less helpful than many surgeons currently believe. And so some non-trivial amount of over-prescription also seems likely.

That’s a fair amount of indirect evidence. While we cannot know for sure, I do feel safe proceeding with the assume that BOB is “often” an exaggeration.

So now what about the value of BOB’ing when it is not an exaggeration? Does accuracy justify it?

•

Part II: Should we ever say “bone-on-bone”? Is it a nocebo if it’s true?

There are strong reasons to avoid the words “bone-on-bone,” and I’ll review those. This has been my bias for years — not a strong one, but clear.

But there are also reasons some why BOB should be spoken, sometimes — reasons I discovered as I explored this topic. I will even retract my attempt to bolster my bias with Buddhist wisdom above, because I got that wrong, and use it to argue the other way! To my surprise, I don’t think BOB deserves all the scorn that gets heaped on it.

And the scorn does get heaped!

It has become fashionable for healthcare professionals to virtue signal with their outrage about how often arthritis is described as “bone on bone.” In their zeal, they can end up minimizing severe arthritis itself, which is going too far… and then often brain-blaming instead, which strikes me as just replacing one nocebo with another.

For instance, a physiotherapist ranting about this on social media wrote that he “hates” BOB, and that the words are “simply referring to the presence of some degeneration.”

Some? Some?! That’s like saying a third degree burn is “simply referring to the presence of some discolouration.” BOB clearly doesn’t just mean “some” degeneration — it means a lot of degeneration!

Then he cited Culvenor et al. to prop up his point that BOB’s not so bad: “up to 43%” of older asymptomatic people had signs of arthritis.14 But those pain-free people had any sign, not signs of severe arthritis. BOB isn’t as bad as people think, but this isn’t the way to make that point. He needed a much different study, showing how many asymptomatic people have severe signs of arthritis!

But no such study exists.

Meanwhile, clearly severe arthritis does exist, and can be extremely painful, and bullshitting people about that isn’t helping anyone.

So how should severe arthritis be described? Well, a Buddhist would say “it depends”…

Part two is about 2200 words (7m read) for members-only for now. If you scroll down, there is a bit of a summing up free to all.

Part I of this article was originally released as a members-only blog post, but has now been let out of the pay-pen. Part II is just for members for now, but I’ll probably set it free in time. I don’t like to paywall my content! So come back in six months and the whole thing will likely be available. Or, better yet, sign-up now to support this kind of science journalism (before it goes extinct).

Most PainScience.com content is free and always will be.? Membership unlocks extra content like this for USD $5/month, and includes much more:

Almost everything on PainScience.com is free, including most blog posts, hundreds of articles, and large parts of articles that have member-areas. Member areas typically contain content that is interesting but less essential — dorky digressions, and extra detail that any keen reader would enjoy, but which the average visitor can take or leave.

PainScience.com is 100% reader-supported by memberships, book sales, and donations. That’s what keep the lights on and allow me to publish everything else (without ads).

- → access to many members-only sections of articles +

And more coming. This is a new program as of late 2021. I have created twelve large members-only areas so far — about 40,000 words, a small book’s worth. Articles with large chunks of exclusive content are:

- Does Epsom Salt Work?

- Quite a Stretch

- Heat for Pain and Rehab

- Your Back Is Not Out of Alignment

- Trigger Point Doubts

- Does Fascia Matter?

- Anxiety & Chronic Pain

- Does Massage Therapy Work?

- Does Posture Matter?

- A Deep Dive into Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness

- Does Ultrasound or Shockwave Therapy Work?

- A Painful Biological Glitch that Causes Pointless Inflammation

- Guide to Repetitive Strain Injuries

- Chronic, Subtle, Systemic Inflammation

- Vitamins, Minerals & Supplements for Pain & Healing

- Reviews of Pain Professions

- Articles with smaller members sections (more still being added):

- → audio versions of many articles +

There are audio versions of seven classic, big PainSci articles, which are available to both members and e-boxed set customers, or on request for visually impaired visitors, email me. See the Audio page. ❐

I also started recording audio versions of some blog posts for members in early 2022. These are shorter, and will soon greatly outnumber the audio versions of the featured articles.

- → premium subscription to the PainSci Updates newsletter +Sign-up to get the salamander in your inbox, 0–5 posts per week, mostly short, sometimes huge. You can sign-up for free and get most of them; members get more and their own RSS feed. The blog has existed for well over a decade now, and there are over a thousand posts in the library. ❐

Pause, cancel, or switch plans at any time. Payment data handled safely by Stripe.com. More about security & privacy. PainScience.com is a small publisher in Vancouver, Canada, since 2001. 🇨🇦

The salamander’s domain is for people who are serious about this subject matter. If you are serious — mostly professionals, of course, but many keen patients also sign-up — please support this kind of user-friendly, science-centric journalism. For more information, see the membership page. ❐

PREVIEW: Headings in the members-only area…

- Would the Buddha say “bone-on-bone”? A 2600-year-old lesson in medical ethics and communication

- Specifically, it depends on the symptoms

- Saying “bone-on-bone” can really spook people

- Bone-on-bone isn’t anywhere near as bad as it sounds — but being “scared still” is a disaster!

- The power of BOB spooks people into surgery they don’t need yet (and might never)

- Why might saying bone-on-bone be okay sometimes? (At the right time, in the right way.)

- The Brain Blamers: BOB-denial can be gaslighting

- What if the truth was reassuring?

Would the Buddha say “bone-on-bone”? A 2600-year-old lesson in medical ethics and communication

In the introduction, I wrote that there is a “Buddhist tenet” that you should ask yourself if what you have to say is true, helpful, and kind — implying that BOB probably doesn’t meet those criteria, and therefore Buddha has your back if you think BOB should bever be said. It’s nice to have a Buddhist endorsement for your position, isn’t it?

I got it wrong, though. I’m no Buddhist scholar. I didn't know that the true/helpful/kind version was greatly dumbed down until reader Paul O. pointed out that there are actually six rather complicated criteria for deciding what is worth saying … and the original, he writes, “makes your ‘kindness’ criterion on its own misleading.”15 So yeah… I used oversimplified ancient wisdom to score a cheap point, didn’t check my source, and got busted!

But I love getting schooled, and the actual citation is so much more interesting.

The Buddha mostly advises against speaking, but there’s specifically an exception for using words that are beneficial despite being hard to hear! Beneficial bad news is allowed! Maybe!

In such cases, the Buddha was indeed inclined to speak, but (and I love this) with “a proper sense of timing.”

Indeed.

And what if words are not beneficial, despite being true? Well, in that case, “he does not say them”! Kindness is beside the point. What counts is the benefit. Fascinating. And, somewhat hilariously, even six detailed tenets still basically boils down to it depends.

So is it beneficial to speak of “bone-on-bone”? Or not? (And what’s the right timing?)

This photo of the Great Buddha of Kamakura was taken by my father, Bob Ingraham, while he was stationed in Japan with the US Navy, before being shipped off to Vietnam, where a bullet destroyed his femur and set him up for knee arthritis in a big way … which I will bring up again below as a good BOB case study.

Specifically, it depends on the symptoms

Probably no one with minor symptoms should ever be told that their arthritis is severe, in any words, “bone-on-bone” or otherwise — it’s too discouraging for someone who still has too much cause to be optimistic.

It is possible to have minor symptoms with what looks like severe arthritis on an x-ray. These patients can have an excellent prognosis. Many will have rough patches, but — if you don’t tell them — some people will never even know that they have “severe” arthritis (or not for quite a long time).

Severe arthritis can be mild? Citation needed, but it’s missing. I’m afraid that there is no direct evidence of this to the best of my knowledge. It seems patently obvious from my own clinical experience, and talking to many experts over the years, but I can’t point to hard prognosis data to back it up. Strangely. As far as I can tell, no one's bothered to check. Maybe someday.

SO I believe there is plenty of hope for many people with BOB. And, for those who have only experienced minimal suffering so far, I don’t think that hope should be preemptively menaced with the melodrama of BOB.

Saying “bone-on-bone” can really spook people

There are also reasons to avoid saying BOB even when a patient is already suffering quite a lot. It’s hard to overstate the degree to which BOB intimidates people.

People cannot easily “un-see” anything that is revealed by any imaging, nor “un-hear” an intimidating interpretation of it. Once BOB has been shown/said, it is often just game-over for nuance. We are strongly prone to thinking, “Welp, that’s it for that joint! It’s just useless now, and there’s no hope, and I have to be super careful with it for the rest of my life. No more walks for me.”

That’s a bad take even for people in a lot of pain.

But that kind of thinking may still happen, even with a big effort to discourage it. People are easily misled in the direction of the fearful belief that their body is like a fragile machine that wears out and breaks down — because that simplistic model is amazingly prevalent in our world, familiar and seductive. It is essentially the only thing that most people think they know about musculoskeletal medicine.16

All our lives, we are inundated with ideas and advice and therapies and products that harmonize with that. We need to be stabilized, aligned, braced, balanced, adjusted! It’s wrong in so many ways … and yet still overwhelmingly dominant in orthopedics, sports medicine, and all the manual therapies.

In other words, BOB harmonizes powerfully with existing fears and misconceptions, making it a bit of a psychological wrecking ball.

Bone-on-bone isn’t anywhere near as bad as it sounds — but being “scared still” is a disaster!

The main argument against BOB-saying is that it doesn't just spook people, but specifically spooks them into sedentariness and disability that is going to make things worse, not better.

As mentioned, severe joint degeneration is not a death sentence for a joint. Advanced arthritis can have surprisingly mild symptoms, symptoms that come and go over the years. How it progresses has more to do with general health and fitness than wear and tear.

Not only are we not fragile, but fearful sedentariness discourages exactly what people need most: as much activity as pain reasonably allows! Bunzli et al.:17

“Common misconceptions about knee arthritis appear to influence patients’ acceptance of nonsurgical, evidence-based treatments such as exercise and weight loss. Once the participants in this study had been ‘diagnosed’ with ‘bone-on-bone’ changes, many disregarded exercise-based interventions which they believed would damage their joint, in favor of alternative and experimental treatments, which they believed would regenerate lost knee cartilage.”

Osteoarthritis is not a “wear-and-tear” disease. How do we know this? Many ways:

- Osteoarthritis is almost twice as common as it was before the industrial revolution, but not because of stress on joints.18

- It’s obviously not mainly about stress on joints, because it’s very prevalent in obese people … in the hands!19

- And walking and running don’t make it worse!20

- If it’s not the wear and tear, then what is it? Well, there’s a link between heart disease and osteoarthritis.21

- Summing all that up in broad strokes, a 2023 scientific review by Lynskey et al. compiled a pile of evidence showing that seemingly mechanical conditions like arthritis and tendinopathy are much more about metabolic health than physical stresses.22 Arthritis is basically an inflammatory disease.23

And so sedentariness and being out of shape is much more dangerous than overdoing it occasionally with your bum knee. Which means that it’s a terrible idea to unnecessarily scare people away from their well-known best option: staying active.24 It’s not that exercise is a miracle cure for arthritis, severe or otherwise — it’s definitely not25 — but it is vital for other well-established reasons,26 and so it’s a disaster if people avoid loading that isn’t the problem.

Here’s the same message in different words from Dr. Howard Luks, an orthopedic surgeon who admirably operates as little as possible:

Telling a patient that they have “bone on bone” X-rays or that they possess the knee of a 90-year-old is more harmful than informative. While attempting to convey the severity of the condition, these phrases can, and often do, inadvertently lead to a fear-driven cessation of all physical activities. Running does not cause arthritis to worsen. It just doesn’t. As I often tell people in my office who think that running led to the need for a knee replacement. Your running didn’t lead to your knee replacement; your running enabled you to keep your natural knee much longer than you would have otherwise.

When patients hear that their joints are severely deteriorated, they might believe the best course of action is to reduce or completely stop activities to “preserve” their knees. This belief is perhaps well-intentioned, but it is counterproductive and wrong. As mentioned earlier, OA is not primarily a result of mechanical stresses but a biological issue related to cartilage repair mechanisms and inflammation. Consequently, inactivity may worsen metabolic health, thereby increasing inflammation and exacerbating OA. The risks associated with inactivity are far more consequential than those associated with exercising.

Contrary to the notion of preserving joints through inactivity, staying active has numerous benefits for those with OA.

The power of BOB spooks people into surgery they don’t need yet (and might never)

Joint replacement is the right choice for some people, but I think it’s fair to say that it’s over-prescribed (see above, and see Knee Replacement Surgery Doubts). It’s just not as good a solution as we’d like, to a problem that is routinely not as bad as we think. Anything that inflames that over-prescription is best avoided.

Exaggerated claims of bone-on-bone are obviously a major culprit. Surgery would plummet if no one ever heard BOB when it was bullshit.

But even when BOB is true, it effortlessly moves the emotional needle towards more drastic solutions. Desperate times call for desperate measures, right? So maybe we should avoid strongly implying with the power of BOB that times are “desperate”!

Why might saying bone-on-bone be okay sometimes? (At the right time, in the right way.)

You can’t avoid it! There are clinical scenarios where it might make sense to talk about BOB judiciously.

Most obviously, patients talk about BOB. Often because some professional has already spilled the BOB beans. They'll bring it up!

The phrase is so unavoidable that maybe it’s just good proactive damage control to get out in front of it. Acknowledge and reassure! “BOB is often bullshit, so let’s talk about it. Yes, technically you have BOB … but … ”

The Brain Blamers: BOB-denial can be gaslighting

The refusal to say BOB often comes with a well-known way of pain gaslighting: attributing pain to something other than the state of the joint. If not the joint tissues, then what?

The mind, of course. Fearfulness. These clinicians are the Brain Blamers.

Many professionals are surprisingly keen to minimize the role of pathology and injury in pain (secondary pain), the better to overzealousy (and conveniently) blame it on the power of the mind/brain to “amplify” pain (primary pain, “nociplastic” pain, in which pain itself is the disease).27 When professionals talk about this in the office — maybe in a general way, or maybe as a more deliberate attempt to Explain Pain — the subtext is always “you’d be fine if you weren’t so scared of your knees.”

And sometimes it’s just the text. It sounds ridiculous, but I’ve heard it said in earnest with my own ears, in my own clinical situation — and I’ve heard from countless readers about being subjected to such bollocks. This is a phenomenon that more and more professionals are starting to push back against (like this very fresh example, a Facebook post).

The mind is involved in pain in a variety of ways, no doubt.28 But I doubt it’s responsible for most arthritis pain, and I think we should avoid implying that by scoffing too hard at BOB, like it doesn't matter. BOB matters a lot.

What if the truth was reassuring?

Patients are unanimous: “don’t bullshit me.” They want healthcare professionals to “tell it like it is.” The idea of minimizing the seriousness of a condition is appalling to most people in principle. We don’t necessarily know what’s good for us, and most of us like to think that we are tougher than we actually are … but we can smell comforting bullshit a mile away, and they will be annoyed by it, whether they should be or not.

Candidly “telling it like it is” also isn’t necessarily scary (or not only scary). There is another possible emotional reaction that’s quite valuable: the cold hard truth might also be validating and empathetic. When patients have severe pain, they like having a severe explanation. Paradoxical relief is a real thing. Uncertainty and frustration are a huge part of having chronic pain, even a common kind like arthritis. The clarity offered by a vivid explanation for pain can be a relief despite the bad news.

One of the principle qualities of pain is that it demands an explanation.

Plainwater, by Anne Carson

So frankness about BOB can really work well for a certain kind of patient.

But it should be followed by frankness about the fact that it is often not nearly as bad as it sounds, and strong encouragement to remain as active as possible.

↑ MEMBERS-ONLY AREA ↑

Bob has BOB

While I was working on this article, I had a long conversation with my father, who is named Bob, and has BOB — or so he has been told. Bob has BOB! Or does he?

Either way, he is not living very peacefully with his arthritis lately.

We talked about the highs and lows, about the capricious nature of it, and how to account for that. Despite being told he had BOB a long time ago, twenty years or something, he has now lived with his “severe” arthritis for many years … and it often doesn’t feel severe. But then it does again for a while. And then it stops. It comes and goes on the tides of unknown physiological variables. And probably emotional ones, too (the brain gets some blame).

So the conversation was all about how his pain is not “all in his mind” or “all in his joints.” It’s always a hybrid. Which often results in surprisingly low pain and high function despite what looks like cartilage carnage.

But it also often results in high pain and low function! Such is life. Many kinds of pain come and go and then come again.

BOB is complicated. And so there is no simple answer to whether or not to say it. It’s like the Buddha said: “It depends.”

So is BOB a nocebo or not?

It definitely can be. Without context and empathy, it probably is. In many cases, it probably does do real harm. It isn’t out of place on a list of noceboes.

But it’s probably a bad idea to demonize it as a terrible nocebo, without nuance. Because it is real sometimes, and because the term can’t be avoided anyway, and because it is often avoided for gaslighty reasons — excessive brain-blame — and because it can also be declawed and used to validate, empathize, and just, y’know, not bullshit.

About Paul Ingraham

I am a science writer in Vancouver, Canada. I was a Registered Massage Therapist for a decade and the assistant editor of ScienceBasedMedicine.org for several years. I’ve had many injuries as a runner and ultimate player, and I’ve been a chronic pain patient myself since 2015. Full bio. See you on Facebook or Twitter., or subscribe:

What’s new in this article?

Four updates have been logged for this article since publication (Jun 28th, 2024). All PainScience.com updates are logged to show a long term commitment to quality, accuracy, and currency. more

Like good footnotes, update logging sets PainScience.com apart from most other health websites and blogs. It’s fine print, but important fine print, in the same spirit of transparency as the editing history available for Wikipedia pages.

I log any change to articles that might be of interest to a keen reader. Complete update logging started in 2016. Prior to that, I only logged major updates for the most popular and controversial articles.

See the What’s New? page for updates to all recent site updates.

2024 — Miscellaneous minor improvements, added audio versions, integrated with other closely related articles, especially Knee Replacement Surgery Doubts.

2024 — Extensive minor improvements.

2024 — Publication.

2024 — First “draft” published as a blog post (actually it was quite a polished members-only post, but also destined to be the introduction to this longer article).

Notes

- Many popular quotations are pithier versions of a more nuanced original, or sometimes just wordier, but this is a particularly extreme case. The Buddha’s tenets for speech are much richer than this, and directly relevant. The dumbed-down version will do for the moment, but I’ll return to this later on where the full Buddhist is really useful.

- Hunter DJ, Bierma-Zeinstra S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2019 Apr;393(10182):1745–1759. PubMed 31034380 ❐

- Bunzli S, O’Brien BHealthSci P, Ayton D, et al. Misconceptions and the Acceptance of Evidence-based Nonsurgical Interventions for Knee Osteoarthritis. A Qualitative Study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019 Jun. PubMed 31192807 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 52253 ❐

- Pi SW, Lee BD, Lee MS, Lee HJ. Ensemble deep-learning networks for automated osteoarthritis grading in knee X-ray images. Sci Rep. 2023 Dec;13(1):22887. PubMed 38129653 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 51491 ❐

- Köse Ö, Acar B, Çay F, et al. Inter- and Intraobserver Reliabilities of Four Different Radiographic Grading Scales of Osteoarthritis of the Knee Joint. J Knee Surg. 2018 Mar;31(3):247–253. PubMed 28460407 ❐

- Klara K, Collins JE, Gurary E, et al. Reliability and Accuracy of Cross-sectional Radiographic Assessment of Severe Knee Osteoarthritis: Role of Training and Experience. J Rheumatol. 2016 Jul;43(7):1421–6. PubMed 27084912 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 51489 ❐

Surely arthritis grading is more reliable with severe osteoarthritis? Yes, but this test shows that it still well short of perfect, even with the most dramatic signs. Even lowly medical students could usually see the same knee nastiness as an experienced surgeon, but not always.

- Vier D, Louis T, Fuchs D, et al. Radiographic assessment of the subtalar joint: An evaluation of the Kellgren-Lawrence scale and proposal of a novel scale. Clin Imaging. 2020 Mar;60(1):62–66. PubMed 31864202 ❐

- Siemieniuk RAC, Harris IA, Agoritsas T, et al. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee arthritis and meniscal tears: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2017 May;357:j1982. PubMed 28490431 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 52778 ❐

These guidelines “make a strong recommendation against the use of arthroscopy in nearly all patients with degenerative knee disease … ” regardless of “imaging evidence of osteoarthritis, mechanical symptoms, or sudden symptom onset.” The authors believe this is the last word on the subject: “further research is unlikely to alter this recommendation.”

- Degen RM, Lebedeva Y, Birmingham TB, et al. Trends in knee arthroscopy utilization: a gap in knowledge translation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020 Feb;28(2):439–447. PubMed 31359100 ❐

- Wasserburger JN, Shultz CL, Hankins DA, et al. Long-term National Trends of Arthroscopic Meniscal Repair and Debridement. Am J Sports Med. 2021 May;49(6):1530–1537. PubMed 33797976 ❐

- Zhu KY, Acuña AJ, Samuel LT, Grits D, Kamath AF. Hyaluronic Acid Injections for Knee Osteoarthritis: Has Utilization Among Medicare Beneficiaries Changed Between 2012 and 2018? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2022 05;104(10):e43. PubMed 35580316 ❐

- Louw A, Diener I, Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Puentedura EJ. Sham Surgery in Orthopedics: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Pain Med. 2016 Jul. PubMed 27402957 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 53458 ❐

This review of a half dozen good quality tests of four popular orthopedic (“carpentry”) surgeries found that none of them were more effective than a placebo. It’s an eyebrow-raiser that Louw et al. could find only six good (controlled) trials of orthopedic surgeries at all — there should have been more — and all of them were bad news.

The surgeries that failed their tests were:

- vertebroplasty for osteoporotic compression fractures (stabilizing crushed verebtrae)

- intradiscal electrothermal therapy (burninating nerve fibres)

- arthroscopic debridement for osteoarthritis (“polishing” rough arthritic joint surfaces)

- open debridement of common extensor tendons for tennis elbow (scraping the tendon)

Surgeries have always been surprisingly based on tradition, authority, and educated guessing rather than good scientific trials; as they are tested properly, compared to a placebo (a sham surgery), many are failing. This review of the trend does a great job of explaining the problem. This is one of the best academic citations to support the claim that “sham surgery has shown to be just as effective as actual surgery in reducing pain and disability.” The need for placebo-controlled trials of surgeries (and the damning results) is explored in much greater detail — and very readably — in the excellent book, Surgery: The ultimate placebo, by Ian Harris.

- Skou ST, Roos EM, Laursen MB, et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Total Knee Replacement. N Engl J Med. 2015 Oct;373(17):1597–606. PubMed 26488691 ❐

(See also Skou 2018, a follow-up study that basically extended the trial, adding more data: “Combined reporting of the two trials allowed more in-depth comparison of available treatment options.”)

Skou et al. found a lots of people who weren’t eligible for surgery for various reasons. Some of those were virtually ignored (just given educational pamphlets, the “basically nothing” group), and the rest were given the best possible care, basically everything medicine could throw at them that wasn’t surgery: exercise, education, dietary advice, use of insoles, and pain medication, and all with regular guidance from physicians and physical therapists. And then those groups were compared to patients who did get TKR. The results of high quality non-surgical care were definitely better than nothing, literally, but nowhere near as good as the TKR results.

- Culvenor AG, Øiestad BE, Hart HF, et al. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis features on magnetic resonance imaging in asymptomatic uninjured adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2019 Oct;53(20):1268–1278. PubMed 29886437 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 51480 ❐

This systematic review and meta-analysis of dozens of studies of thousands of knees showed that signs of arthritis seen on MRI scans are common in people with no symptoms, and no history of injury. In young adults, asymptomatic signs of degeneration ranged from 4–14% in younger adults and 19–43% in adults over age 40.

This should not be overinterpreted as evidence that severe arthritis can be asymptomatic; that is possible, but this data doesn't show it.

Bodhi, B. (Trans.). (1995). The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Majjhima Nikāya. MN 58. Wisdom Publications.

The six criteria for deciding what is worth saying are as follows:

- “In the case of words that the Tathagata knows to be unfactual, untrue, unbeneficial (or: not connected with the goal), unendearing & disagreeable to others, he does not say them.

- “In the case of words that the Tathagata knows to be factual, true, unbeneficial, unendearing & disagreeable to others, he does not say them.

- “In the case of words that the Tathagata knows to be factual, true, beneficial, but unendearing & disagreeable to others, he has a sense of the proper time for saying them.

- “In the case of words that the Tathagata knows to be unfactual, untrue, unbeneficial, but endearing & agreeable to others, he does not say them.

- “In the case of words that the Tathagata knows to be factual, true, unbeneficial, but endearing & agreeable to others, he does not say them.

- “In the case of words that the Tathagata knows to be factual, true, beneficial, and endearing & agreeable to others, he has a sense of the proper time for saying them. Why is that? Because the Tathagata has sympathy for living beings.”

- “Structuralism” is the excessive focus on crookedness and “mechanical” problems as causes of pain. It has been the dominant way of thinking about how pain works for decades, and yet it is a source of much bogus diagnosis. Structuralism has been criticized by several experts, and many studies confirmed there are no clear connections between biomechanical problems and pain. Many fit, symmetrical people have severe pain problems! And many crooked people have little pain. Certainly there are some structural factors in pain, but they are generally much less important than messy physiology, neurology, psychology. Structuralism remains dominant because it offers comforting, marketable simplicity. For instance, “alignment” is the dubious goal of many major therapy methods, especially chiropractic adjustment and Rolfing. See Your Back Is Not Out of Alignment: Debunking the obsession with alignment, posture, and other biomechanical bogeymen as major causes of pain.

- Bunzli 2019, op. cit.

- Wallace IJ, Worthington S, Felson DT, et al. Knee osteoarthritis has doubled in prevalence since the mid-20th century. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Aug;114(35):9332–9336. PubMed 28808025 ❐ Knee osteoarthritis is thought of as a “wear-and-tear” problem aggravated by weight and age. In this experiment, this assumption was tested for the first time using “long-term historical or evolutionary data.” They looked at the skeletal remains of older people with a well-documented body mass index from the last two centuries (industrial and post-industrial); they also looked at prehistoric knees. The prevalence of osteoarthritis has roughly doubled in recent history (20th century) — and that number didn’t change when weight and age were factored out. The implications are clear: loading and longer lifespans are almost certainly not the cause of knee arthritis!

- Jiang L, Xie X, Wang Y, et al. Body mass index and hand osteoarthritis susceptibility: an updated meta-analysis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2016 Dec;19(12):1244–1254. PubMed 28371440 ❐

- Voinier D, White DK. Walking, running, and recreational sports for knee osteoarthritis: An overview of the evidence. Eur J Rheumatol. 2022 Aug. PubMed 35943452 ❐

Voiner and White reviewed a lot of reviews of the relationship between exercise and arthritis — an “overview of narrative reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses,” twenty of them. They also threw a dozen original trials into the mix. Their clear conclusion, based on “consistent evidence,” is that arthritis just has nothing to do with common kinds of physical activity and exercise, like walking and running and playing softball. Specifically, the “structural progression” is unrelated to physical activity in the general population.

- Mathieu S, Couderc M, Tournadre A, Soubrier M. Cardiovascular profile in osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis of cardiovascular events and risk factors. Joint Bone Spine. 2019 Nov;86(6):679–684. PubMed 31323333 ❐

- Lynskey SJ, Macaluso MJ, Gill SD, McGee SL, Page RS. Biomarkers of Osteoarthritis-A Narrative Review on Causal Links with Metabolic Syndrome. Life (Basel). 2023 Mar;13(3). PubMed 36983885 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 51282 ❐

Physiology and biochemistry more than anatomy and biomechanics. Take two people with the same physical stresses on the knee and it’ll probably be the borderline diabetic who gets the knee osteoarthritis first.

So what goes wrong with “metabolic health”? It’s a mash-up of what most people know as your risk of heart disease and diabetes — all familiar stuff. You know your metabolic health might be mangled when you are “out of shape” — high blood sugar, high blood pressure, lots of cholesterol in your blood and belly fat. You get out of breath taking a flight or two of stairs. All of this going on at once is known as “metabolic syndrome.”

With apologies to Indiana Jones, it’s not the years or the mileage — it’s the biological context!

- Robinson WH, Lepus CM, Wang Q, et al. Low-grade inflammation as a key mediator of the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016 10;12(10):580–92. PubMed 27539668 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 52712 ❐

- Weng Q, Goh SL, Wu J, et al. Comparative efficacy of exercise therapy and oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and paracetamol for knee or hip osteoarthritis: a network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. 2023 Jan;57(15):990–996. PubMed 36593092 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 51421 ❐

This enormous meta-analysis concludes that exercise is a modestly effective treatment for hip/knee arthritis in the short term:

Exercise has similar effects on pain and function to that of oral NSAIDs and paracetamol. Given its excellent safety profile, exercise should be given more prominence in clinical care, especially in older people with comorbidity or at higher risk of adverse events related to NSAIDs and paracetamol.

The data also shows diminishing returns over time, dwindling to a trivial benefit.

But this data shows that exercise is quite safe and somewhat helpful — and therefore also obviously not harmful.

This is not surprising science, of course. That conclusion is based on one-hundred and fifty-two trials. 😮 That is a whole bunch of trials! The effect of exercise on arthritis is one of the better studied questions in the science of pain. We have seen this result before, many times. But it’s nice to see the data synthesized in a mighty meta-analysis for the BJSM.

Nor is it especially exciting science: pain relief in the same league as the common pain meds isn’t exactly dazzling stuff. Last I checked, no one was claiming that their ibuprofen is a miracle cure for their arthritis. Also, your mileage may vary in a big way; not everyone is going to get a pain-relief benefit from a workout, and some will actually get the opposite (“exercise intolerance” is common in people with chronic pain). But ibuprofen can fail and backfire too… and, hoo boy, that stuff is a lot more dangerous than exercise (see Bally), and many people cannot take NSAIDs at all.

The important conclusion here is that exercise might actually help arthritis, and definitely doesn’t generally make it worse.

- Holden MA, Hattle M, Runhaar J, et al. Moderators of the effect of therapeutic exercise for knee and hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. The Lancet Rheumatology. 2023 Jul;5(7):e386––e400. PubMed 38251550 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 51623 ❐

This is a 2023 review of mostly the same data as past reviews of exercise for hip and knee osteoarthritis … but this one’s fancier, and maybe more valuable than the rest of them put together. It’s an analysis of “individual patient data,” which is a more hardcore kind of meta-analysis. Instead of studying the pooled results of trials, they get the original data and started from scratch. It’s a lot of work, and Melanie Holden and fifty-three colleagues did the IPD thing for 4200 participants in 31 trials.

The results seem nice at first, highlighting a “positive overall effect of therapeutic exercise on pain and physical function in individuals with knee or hip osteoarthritis, compared with non-exercise controls.” Sounds familiar.

But it’s a small effect. Very small.

“This effect is of questionable clinical importance, particularly in the medium and long term.”

And that’s the news here. They concluded that exercise moved the needle just 6 points on a 100-point pain scale (on average). That’s much less than what people can even detect! And you cannot care about what you can’t feel.

And then it got worse beyond three months. 😬

We’ve always known exercise for arthritis delivered only a modest benefit, but there have been ominous signs that even that much may have been overestimated. For instance, a clever 2022 trial that found that it was no better than a placebo. And now this!

But it’s worth emphasizing that the benefit is almost certainly real, albeit small, and it’s an average, so some people will do better. And there are still many other benefits to exercise, of course.

Another important caveat is that there could also still be a substantial very long-term benefit — this data simply doesn’t address that possibility. No data does!

![Photo of a set of indoor stairs. Each stair is labelled with a cumulative calorie-count in half calories increments: 0.5 calories, 1.0 calories, 1.5 calories, up to 6.5 at the top of the photo.]()

The calorie-counting stairs (click to zoom). Stairs are the most ubiquitous, accessible “gym equipment” in the world

It has been said that exercise is the closest thing there is to a miracle cure. “All the evidence suggests small amounts of regular exercise (five times a week for 30 minutes each time for adults) brings dramatic benefits,” we “age well” when we are active (Gopinath): less anxiety (Schuch), prevention of dementia (Smith) and a laundry list of other diseases (Pedersen), and as little as just 10 minutes per week might push back death itself (Zhao). It’s also superb for sleep quality (Giannaki). It may even be good medicine for musculoskeletal injuries (more info).

But why is it so awesome? Exertion mobilizes extensive networks of biological resources that are relatively dormant while we’re watching Netflix. It’s biologically “normalizing,” pushing systems to work the way they are supposed to work. Exercise cannot normalize everything, but it does stimulate an incredibly broad spectrum of biological function — way more than any medicine, supplement, or superfood.

- There are two main kinds of pain: nociceptive and neuropathic. Nociceptive pain is the most familiar because it arises from damaged tissue, like a cut or a burn. Neuropathic is more rare, because it is caused by damage to the damage-reporting system itself, the nervous system. Some pain, like fibromyalgia pain, doesn’t fit into either category, and was historically and poorly labelled “functional pain,” now most commonly called “nociplastic.” Pain is also either somatic (skin, muscle, joints) or visceral (organs). See The 3 Basic Types of Pain: Nociceptive, neuropathic, and “other” (and then some more).

- Pain is a volatile, unpredictable experience that might get amplified by an overprotective brain. If the brain produces all pain — and technically it does, just like everything else we experience — maybe that means we can think pain away? Probably not with pure willpower or an attitude adjustment. But perhaps we can influence pain, indirectly, if we understand it — a few Jedi pain tricks. This isn’t about treating the root causes of pain, but the potential to tinker with the perception of it. Pain is fundamentally an alarm, and maybe we can convince our brains that it doesn’t need to be so loud, with methods like increasing confidence through education about pathology and pain itself (“Explain Pain”), avoiding nocebo, limiting “pain talk,” and many more. These are not easy or proven paths to pain relief, but all of them have some potential. See Mind Over Pain: Pain can be profoundly warped by the brain, but does that mean we can think the pain away?