Healing Time

Can healing be hurried? Would we even notice if it was?

Healing speed is of great interest, and people often believe that treatment X helped them to heal faster. It’s a common marketing claim too, of course. A perfect current example is platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections, which are often branded as a “regenerative” treatment that accelerates the return of injured tissues to a normal tissue state.

Unfortunately, most patients have no basis of comparison, no idea what constitutes a normal healing time — because there is no such thing. Experienced clinicians don’t really know what a normal healing time is either.1 People often recover faster or slower than expected for reasons no one can ever know. We also seem to recover faster or slower depending on which psychological “goggles” we have on (optimistic, pessimistic, etc).

Even if natural variation in healing times didn’t obscure the effects of treatments, it still wouldn’t be possible to know if any treatment helped us heal “faster,” because we can never know in any given case how long healing would have taken without the treatment. You also don’t know what will happen the next time (it could be completely different). The only possible way to settle such questions and confirm a faster average recovery time — especially if it’s only a little bit faster — is with carefully designed scientific testing, and quite a bit of it.

Biology (mostly) cannot be rushed

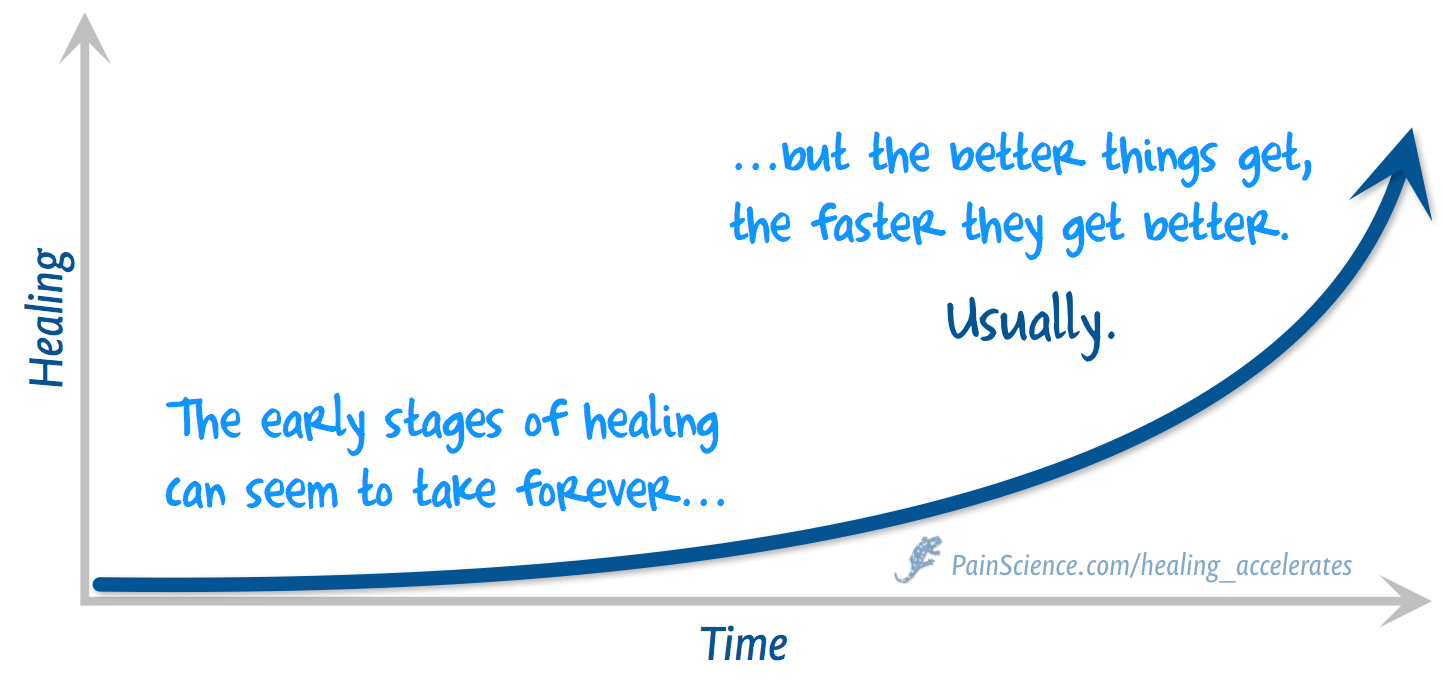

Healing mostly just takes what it takes. It usually starts slowly and then accelerates, as long as nothing gets in the way or goes wrong. A great deal of treatment and therapy are simply a matter of making sure nothing gets in the way or goes wrong — which can be worthwhile. They often get credit for that natural acceleration phase.

Healing in the broadest, subjective sense is recovery from any pathological state, which may have little or nothing to do with any tissue repair that can be sped up. For example, a patient with a tumour may be doomed but otherwise healthy. If the tumour is successfully surgically removed, the patient has “healed” — more or less instantly, just by taking out the cancerous trash.2 It’s certainly “healing” from the perspective of the patient! But almost none of medicine’s greatest hits have anything to do with speeding up the biology of healing.

The main kind of healing that can in principle be accelerated is wound healing, the most literal sort of healing, which is a mix of regeneration and repair: either growing new cells where possible, or patching the damaged area with scar tissue. The more and faster the regeneration, the better, of course … but we’re kind of stuck, for now, with our biological destiny as mediocre regenerators.3

There are also a lot of common problems, especially in musculoskeletal medicine, where there is literally nothing to regrow or patch — and therefore no “healing” to accelerate even in principle. Here’s a few simple examples …

- Nerve impingements, although not as common as people fear, certainly do happen. There’s a problem to solve, but no wound to heal at any speed. Nerve lesions involve damage that heal notoriously slowly, but there’s also no known method of speeding that up.

- Chronic low back pain is notoriously inexplicable — no known biological origin of pain (and many of the suspected ones are red herrings), no tissue to regrow or patch, no healing to accelerate.

- Fibromyalgia is an alarming common disease of just generally being too sensitive — lots of unexplained body pain. What’s to accelerate here? There’s probably no wound to heal at any speed.

- Osteoarthritis involves the degeneration of joints, but cartilage simply does not heal at all, and so again: no healing to accelerate.4 (Even high-tech cartilage regeneration methods don’t actually speed up cartilage healing, they just make it possible at all.)

- Repetitive strain injuries like iliotibial band syndrome or plantar fasciitis are caused not by frank tissue damage, but by a slow motion and very complex tissue fatigue. There are no dead cells to replace, and there may not even be any “fraying” connective tissue — the cells are exhausted from the strain of maintaining the connective tissue around them, and their strain causes pain. There’s little or no damage to repair. Recovery is possible, but mostly by finding the right balance between stimulation and stress on the tissue.5

And so on. The longer you look at it, the more obvious it becomes: “healing” is not one thing, but a thousand different things … most of which cannot be hurried.

Can you vibrate bones back to health? Unlikely

One of the most persistent hopes for accelerated healing is that the stimulation of vibration — delivered by high-frequency sound waves, ultrasound — has peculiar, beneficial effects on cellular behaviour. And one of the best specific examples of this hope is the idea that ultrasound might speed the healing of bone fractures, particularly low intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS). Such an effect, if proven, would certainly be a delightful bit of weird good news about biology. And it would have broad clinical implications: if LIPUS can help fractures heal, it might help any tissue in any kind distress.6

Alas, the effect is probably dis-proven. In 2017, the British Medical Journal published an excellent review with a very negative conclusion for fresh fractures.

What if healing doesn’t happen?

You may not have much control over it, but most healing does progress steadily and even accelerate: the better you get, the faster you get better, a “delicious cycle.” But … what if it doesn’t? Continue reading with Healing Usually Accelerates.

The false humility of “facilitating” healing

It’s a common idea that we heal ourselves and therapies like massage or acupuncture just help us along the way. Paradoxically, it also implies that we can’t do it on our own, or that it would be slower. If seeing a “healer” doesn’t speed up healing, what’s the point?

Facilitating self-healing is a cliché of alternative medicine: it’s sacharine, silly, inspirational-poster nonsense. More technically, it’s a “deepity,” an idea that is either profound but wrong, or true but trivial. If healing actually could be “facilitated,” that would be miraculous. And it’s asserting a claim of an impressive power over patients while also trying to sound like “it was nothing,” a classic humblebrag. Read more: The False Humility of “Facilitating” Healing.

About Paul Ingraham

I am a science writer in Vancouver, Canada. I was a Registered Massage Therapist for a decade and the assistant editor of ScienceBasedMedicine.org for several years. I’ve had many injuries as a runner and ultimate player, and I’ve been a chronic pain patient myself since 2015. Full bio. See you on Facebook or Twitter., or subscribe:

What’s new in this article?

2017 — Science update, cited Schandelmaier et al., an excellent (and completely negative) British Journal of Medicine review of LIPUS for acute fracture/osteotomy healing.

2012 — Publication.

Notes

- Witnessing hundreds or even thousands of cases of the effect of some treatments only confirms that healing time varies wildly depending on countless variables.

- Other good examples are killing infections with antibiotics, curing scurvy with vitamin C, surgically closing a large wound to facilitate healing, or even just putting a Band-Aid on a cut — destroying invaders, stocking up on vital chemicals, facilitating normal-speed wound healing and protecting it from interference, and so on and on.

- There are many critters that are better at regeneration in one way or another, so we know it’s probably possible to improve. However, there are still almost no examples of genuinely upgraded regeneration in medicine, and they are mostly rather exotic.

- Although there are plenty of heavily marketed supplements that claim to be able to stimulate recovery from osteoarthritis, it’s all bollocks.

- In worse cases, the connective tissue does begin to rot and crumble. In this context, “accelerated” healing might be more meaningful: giving a boost to cells, helping them do their job, so that they can catch up on their maintenance schedule without being so exhausted. But no one knows how to do this.

- Schandelmaier S, Kaushal A, Lytvyn L, et al. Low intensity pulsed ultrasound for bone healing: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMJ. 2017 Feb;356:j656. PubMed 28348110 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 52780 ❐ From the abstract: “trials at low risk of bias failed to show a benefit with LIPUS, while trials at high risk of bias suggested a benefit” and “LIPUS does not improve outcomes important to patients and probably has no effect on radiographic bone healing.”