Reluctantly Reconsidering RESTORE

An in-depth analysis of the RESTORE trial of Cognitive Functional Therapy for back pain

Wouldn’t it be amazing to finally start winning the war against low back pain? That bane of our species, our most inevitable misfortune after death and taxes? Imagine!

All you have to do is stop being afraid to move. Which might take some basic coaching. Or a lot of skilled coaching.

Cognitive Functional Therapy (CFT) is a “new” therapy for back pain, “an individualized approach that targets unhelpful pain-related cognitions, emotions, and behaviours that contribute to pain and disability.” It’s making waves and earning praise from the right kinds of people (for a pain nerd like me). This is no hologram bracelet or another spinal traction gadget, but Serious Health Care, the bleeding edge of complex care for a complex problem … and now based on evidence too? Pinch me!

The news about CFT for back pain seemed really great, a bit of a eureka moment, a strong ray of hope for millions of people with chronic back pain. And then I read it more carefully. Now it seems, I dunno… “fine” I guess?

Is the RESTORE trial of CFT what we’ve all been waiting for?1 Maybe. I initially described RESTORE as a “major good news study for back pain” which “validates my career.” I was a bit giddy from a megadose of sweet, sweet confirmation bias. Aahhh, refreshing!

My buzz didn’t last long, though. (Do they ever?) Before the ink was dry, I was already seeking more critical reactions to the paper — my own and from others — and finding them a little too easily for comfort. And so I knew I had to do the intellectually mature thing: nitpick an important study I truly want to love. And there are indeed nits to pick! We are talking about a single study with a high risk of bias that was poorly controlled, enitrely unmasked, relied on self-reported outcomes, and still produced only modest effect sizes. It needs more rigorous replication as badly as any study has ever needed it.

CFT is important because of the significant principles that it is built on. The stakes are high. This is a milestone in the field: RESTORE looks like an unusually good quality scientific experiment for physical medicine. It’s published in a good journal, and it’s about a modality that brings together a bunch of pieces that all the finest smartypants clinicians have been talking about for ages.

So how does it hold up to the baleful gaze of the salamander? This huge article examines CFT and RESTORE in skeptical detail.

Table of contents

- What is this is all about and why does it matter?

- Why did I initially think RESTORE “validates my career”?

- The RESTORE trial from 10,000 feet

- Cognitive Functional Therapy

- The RESTORE trial

- Testing CFT: the design of the trial

- Where’s the pain? Pain was measured, but (weirdly) it was not the focus

- Abundant bloopers and blemishes in RESTORE

- ☝🏻️ the skeptical heart of the article

- I’ve got bad news about the good news

- An even bigger section about the small effect size

- Packaging best practices: CFT for sale

- Lasting results? RESTORE 3 years later

- Summing it all up

- Notes

What is this is all about and why does it matter?

There’s a polished website from the CFT folks — RESTOREbackpain.com — that explains RESTORE … in rather glowing terms. Why not just read that? Why read this huge and informal review?

Because this is not from the CFT folks. This is my more curmudgeonly criticize-with-love version, and I will take the limitations and caveats quite seriously. That more peevish perspective is valuable because RESTORE is an important trial of an important thing — not just CFT, but the principles it rests on.

If you love an idea, don’t forget to criticize it occasionally.

So I did that … and RESTORE fell in my esteem from solid good news to merely mildly promising, I guess. It’s a good study in many ways, even very good in some ways, but it’s only one, and it has real flaws — and I’m not even sure that it was the study we actually needed for this. Much as I want to believe, the benefits did not seem all that impressive when I looked more closely.

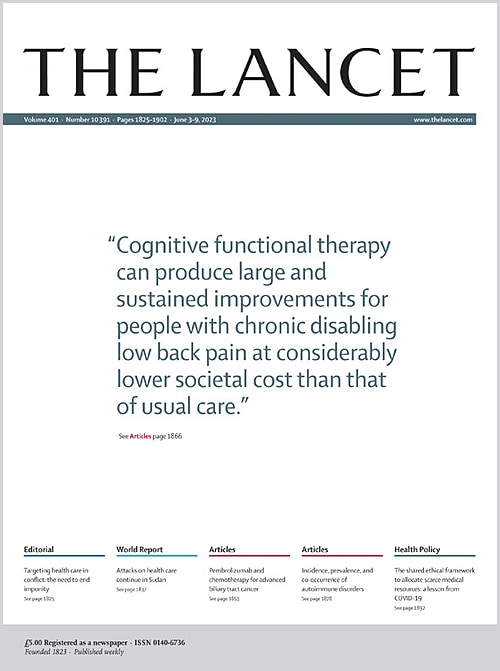

The Lancet editorial about RESTORE is an excellent source in its own right, and it probably deserves to be read as much as the study itself: it’s like a more formal and much shorter version of this post.2

The RESTORE trial didn’t just get published in The Lancet, it was actually FEATURED. The journal put the good-news conclusion right on the cover! Just think about how influential that is. 🤯

Why did I initially think RESTORE “validates my career”?

Cognitive functional therapy is a close match to the kind of care I myself would offer if I were still a clinician. It’s what many of my most respected therapist pals are actually doing.

From about 2008 through 2018, I was inventing something a lot like CFT — as were many others. I think anyone chasing the science in this field — and backing steadily away from obsolete physical therapy dogma, especially the obsession with biomechanics and scannable pathology — has ended up in a CFT-like place. Which is why RESTORE matters: because it’s a test of what an awful lot of progressive healthcare professionals have been up to for the last decade (if not longer).

(And indeed some of those people are exasperated that someone’s trying to “brand” and “package” what they consider to just be a smorgasbord of good science-based care. More on this later in the post.)

A thumbs-up trial of CFT sounds like an endorsement of my thinking for over a decade, so of course my first reaction to it was a nice warm glow. Who wouldn’t want to find that in the hallowed pages of the The Lancet?

But humble pie is always served after the proud appetizer and the excited entrée.

The RESTORE trial from 10,000 feet

This is the first trial of Cognitive Functional Therapy with some oomph.

There have been other promising trials of CFT that I have eagerly cited,34 but not enough to be considered strong evidence. RESTORE might get us there, but it’s still not much of a body of evidence — maybe just a leg of evidence.

It’s also worth noting that not every paper has harmonized with this one, most notably an important 2014 systematic review with a “meh” conclusion about CFT-ish therapies more generally.5

But RESTORE is much more substantive than its predecessors: big, complex, orchestrated by an experienced team, and (cherry on top) published in a top tier journal. These things are a great foundation, but they don’t guarantee an A+. Not everything that glitters in a fancy journal is gold.6

The RESTORE trial beams with good news.7 The authors seem to have declared “victory” in the paper and in the media, without major qualifications and caveats — just a single short paragraph acknowledging some technical limitations. I will give the limitations somewhat more attention. 😜

"Artifacts"

xkcd #1781 © xkcd.com by Randall Munroe I’m not saying this is the case about RESTORE. I’m not saying it isn’t. Mostly it’s just a funny and possibly relevant xkcd.

What actually happens in CFT? Coaching, not fixing

The purpose of the RESTORE trial was to test the effectiveness of Cognitive Functional Therapy. This article is about the trial, but ultimately I am going to have permanent featured article about CFT itself on PainScience.com, and that will go a little something like this…

CFT has three major components:

- Making sense of pain with personalized education, especially challenging common beliefs about pain that lead to fearful movement limitation and over-protection.8 (And, yes, this definitely involves a lot of "pain explaining" — with all the pros and cons that entails, such as the potential for gaslighting explored in summer post.)

- Building confidence. Exposure with ‘control’, graded exposure, challenging fearful expectations with “guided physical behavioural experiments.” Say what now? In better words: try moving like so, and it will probably work out better than you think.

- Lifestyle change, reducing systemic vulnerability to pain by improving health and fitness in general ways. This is valuable for almost any pain patient, and it’s something I’ve been yammering on about for years, and I still am, and I have no reservations about continuing to do so: it’s a terrific strategy that can never be a waste of time, even if it fails to treat pain.

So CFT is more focused on teaching and coaching than the traditional “fixing” style of physical therapy, where therapies are done to the patient.

You might be thinking that it sounds surprisingly basic, but it’s a case of “simple” and not “easy.” The devil is in the details.

About Cognitive Functional Therapy itself: the BPS-ification of back pain care

CFT aims to make something practical out of a fifty-year-old abstract idea: tough healthcare challenges, like chronic pain, require complex personalized care — imagine! mind blown! — rather than just one or two key points of (passive) intervention like a pill or a spinal adjustment.

I am talking about doing healthcare the BPS way, applying the famous “biopsychosocial” model of healthcare, which has been particularly “fashionable” (carefully chosen word there) for the last twenty years or so in musculoskeletal and pain medicine.9 BPS-style care boils down to treating people like people, with lives that matter, relevant to care… a.k.a. “nice” healthcare, which may be especially important in the treatment of pain, because pain is not just about the “bio,” but also about our psychological and social circumstances, our story.

We all sure do hope that BPS-ified care is more effective than passive therapies, but it’s extremely hard to standardize and study. And to the extent that it has, BPS-ification of care has not exactly been a resounding success. For instance, Cormack et al. argued persuasively in 2022 that the BPS model is generally “lost in translation” and chasing it has resulted in “suboptimal musculoskeletal care.”10

CFT involves a lot of working with people not just to encourage them to start moving again, but to do it ways that are a good fit for that individual: needful and/or fun. (Which is also just what you would see with good occupational therapy.)

But CFT is an attempt to make it work, to standardize BPS care (and the RESTORE trial is an attempt to study it).

CFT is BPS-ified care. It “puts into practice the contemporary recommendations for a biopsychosocial approach to care” (Kent).

But it also includes some important special sauce for encouraging movement. It “addresses pain-provocative movement patterns that contribute to low back pain, such as protective muscle guarding and movement avoidance.”

Is CFT a treatment for “psychosomatic” back pain?

Yes. But shhh, don’t say “psycho”! People get upset. And nothing curbs my enthusiasm about CFT more than this one critical detail: a major premise of CFT is that “thoughts and feelings” actually cause back pain. Straight from the science-horses’ mouths:

“CFT is an individualised approach that targets unhelpful pain-related cognitions, emotions, and behaviours that contribute to pain and disability.”

More:

“A key distinguishing feature of CFT, compared with other psychologically informed approaches such as cognitive behavioural therapy, is that CFT addresses pain-provocative movement patterns that contribute to low back pain, such as protective muscle guarding and movement avoidance. Wearable movement sensors enable clinicians to easily measure such movements and explore their relationship to pain, both in the clinical setting and during patients' normal activities at work and recreation.”

These thoughts, feelings, and behaviours that CFT “targets” are specifically fearful. It’s really all about the fighting the fear. This is not just saying “unhelpful thoughts, emotions, and behaviours” are the problem; it’s even an more aggressively psychological focus on “thoughts, emotions, and fears.”

You don’t have to boil that down any further. It’s clearly implied that anxiety is a major driver of back pain, and that is a psychosomatic hypothesis about how back pain works. If you’re spooked into stillness, your back pain experience will be worse. If you can master your fear, it’ll be better. Certainly sounds “psychosomatic” to me.

Sound familiar? Where have we heard that before? Just a slight rewording, and the inspiration for CFT sounds an awful lot like the ideas of Dr. John “Back Pain Is Psychological” Sarno.11 Although Sarno has always been extremely popular, many patients find his all-in-your-head focus to be offensive, and many back pain experts dismiss Sarno as a crank. So it’s not a flattering comparison. CFT is no clone of what Sarno was selling, but there is real overlap. Kent et al. seem to be careful not to say it too loudly and directly, but they definitely appear believe that the keys to back pain are between your ears. Much like Sarno. Who so obviously got rich by drinking his own Kool-Aid for an audience of millions.

I’m not saying they’re wrong, and I’m not saying CFT is bad because it’s pointing a finger at the mind. I have very mixed feelings/views on this. “It’s complicated” is a massive understatement. But CFT is rooted partly in a psychogenic pain hypothesis.12 But it sounds a lot more serious and professional to say “targeting unhelpful pain-related cognitions, emotions, and behaviours” than “you’re in serious chronic pain because you’ve put the fear-whammy on yourself and you’re too spooked to move.”

One of many expressions of the idea that fear causes pain via the mechanism of suppressing movement and activity (while making it seem “wise” by attributing it to Yoda, very crafty; hat tip to Lars Avemarie for inspiring this version, which I revised a bit). While this is not usually seen as an “all in your head” idea, it very clearly blames pain on “fear” with just one causal hop between them.

Going all the way back to the mid 2000s, I had this diagram in my back pain book. At the time, it seemed to be my own invention, and I felt very confident about it. Later that started to feel like overconfidence as I started to see how it’s really just a thinly veiled way to attribute back pain to being scared of it (“it’s all in your head”). But I kept it in there with some careful disclaimers, because it was strongly consistent with the larger CFT-ish story I am still telling to this day.

CFT versus crappy physical therapy business as usual

Some important perspective: even if CFT is much less impressive than advertised, it is probably still the lesser of evils. Maybe by a long shot.

It’s certainly much “less wrong” than the incumbent therapeutic paradigm for back pain. The depressing majority of therapy for back pain is still made of structuralist nonsense like “Your glutes aren’t activating” and “Your fragile and unstable spine is out of line” and “You stubbed your toe in 1994 and never learned to walk properly again and that’s why your back is a mess today.”13

Many professionals need and want some guidelines and clarity about how to move beyond those junky old meat-mechanic ideas. And CFT delivers a well-defined and reasonable alternative. It is something to pick up, rather than baggage to put down.

Structuralism and the medical model are still freakishly dominant, and CFT will have many advocates just because it is a rational alternative that produces care that is, if nothing else, not just stoking simplistic fears about spinal degeneration. Care that is compassionate and curious, and supports the pursuit of safe and enjoyable activities with rational reassurance, and debunking of harmful myths about pain, seems inherently valuable, and far superior to the old paradigm even if it isn’t actually curative.

Care like that should not be unusual. Weirdly, it definitely is.

Many people will defend and promote CFT even without a good study to back them up. They will do so not because it’s evidence-based medicine, but because it’s clearly an improvement over the old ways. And I’m okay with that.

But if professionals are also armed with a seemingly good-news citation about how well CFT works? Potent combo! CFT is probably going to be a big deal.

An illustration of how the old back pain therapy paradigm is “barking up the wrong tree” at things like posture. This is the kind of thing CFT could replace.

Testing CFT: the design of the trial

The RESTORE subjects — the restorees? — were five hundred people with very chronic back pain, four years of it on average; everyone had tried to get help for their back pain, and many had given up (probably in disgust). The study included some patients that usually don’t get included in back pain studies: older people, surgical patients, folks with other major health issues.

So this was quite a diverse group of people with nasty chronic back pain. Kent et al. used their science sorting hat to put them on three teams:

- Team CFT — 7 treatment sessions over 12 weeks, plus a CFT “booster” at 26 weeks.

- Team CFT with Biofeedback — CFT with movement tracking… because it seemed to be helpful in other trials. (The CFT-only group also wore sensors, but wasn’t used to enhance their therapy; it was just extra data.) There were two sensors on the spine, above and below the “low back,” to show low back positions and movement.

- Team Good-Luck-With-That — This “usual care” group just fended for themselves — they got whatever help they could get on their own out in the community. Like they weren’t even part of a study! (And they knew that, and it matters. More on this soon.)

And then the researchers waited until a full year had passed, and checked up on as many of the “restorees” as they could.

Where’s the pain? Pain was measured, but (weirdly) it was not the focus

What happened to the pain seems like the main thing anyone wants to hear from any study of a back pain treatment. But in the wacky world of pain research, pain itself often takes a back seat — it was only a “secondary outcome” here, along with changes in beliefs about pain, movement fear, and satisfaction. I am not a fan of this.

What was the focus, if not pain? The spotlight (the primary outcomes) was on:

- Disability, measured by activity limitation as reported by participants on a questionnaire.

- Bang-for-therapeutic-buck, measured in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) — a rather cryptic yardstick, and somewhat controversial too.

Okay, so then what happened to function and care efficiency? And pain, and changes in beliefs? Of course, you already know that it was reported as very good news. Reported and shouted from the rooftops — that’s the reason we’re gathered here today. So before digging into the specifics, let’s get a bit crazy and talk about the study’s limitations first — a break with scientific reporting tradition.

Abundant bloopers and blemishes in RESTORE

I don’t really think there are any true “bloopers” in the RESTORE trial — that’s just me having fun with heading hyperbole and alliteration. There are, however, copious candidate concerns. There are, arguably, poor trial design choices.

The paper itself barely acknowledges any limitations … which is another kind of limitation. I never want to see a token effort in this department; it’s not a good place for it. Dear researchers: skimp somewhere else! Seeing an awareness of what your study can’t do does wonders for my ability to trust your judgement about what it can do.

(Reminder: I am deliberately finding fault in a study I want to like.)

The potential concerns about the paper are, roughly in order of descending importance, and with quite a lot of elaboration in the footnotes:

- Most important of all — and yet not discussed in the paper, let alone highlighted — RESTORE was not a trial of “efficacy.” It was not sham-controlled trial, which means that it cannot actually show that CFT works, not even in theory (let alone in practice).14

- And how would it be placebo-controlled? A good question that needs a big footnote of an answer!15

- Even if RESTORE had demonstrated “efficacy,” that’s not the same thing as showing that it would also be “effective” in the real world.16 And I’m not saying that it should have been — effectiveness trials are another whole kettle of fish. But it wasn’t that, and it’s important context.

- And what did it show, if it didn't even show efficacy, let alone effectiveness? Good question! With no clear answer.

- RESTORE was also an unblinded (or unmasked) trial, which supercharges the risk of “performance bias,” more charmingly known as the frustrebo effect. The danger is that the results aren’t showing that the CFT recipients got better… but rather that people deprived of that opportunity got relatively worse, because they were frustrated not to be getting the good stuff.17

- The follow-up analysis three years later claimed the effects on disability and pain persisted unchanged for an (almost unbelievable) three years, the holy grail of “lasting results” … but almost 40% of their subjects failed to check-in, making the result even harder to believe. More on this below.

- Disability as a primary outcome is defensible, but I’ll never be entirely okay with it myself.

Finding ways to function better in spite of pain is important, obviously — and sometimes the only realistic goal — but it should never be confused with actually treating pain. - Significant risk of bias. RESTORE’s authors clearly have a dog in this fight, and they are vigorously promoting a point of view on how therapy should be done.18

- The null result for biofeedback is a red flag. Adding a theoretically sound, data-rich adjunct really should have added value to CFT — a good additional “active ingredient,” if the main one works the way it’s supposed to. That’s why they did it. But biofeedback did not boost the benefit of CFT, and so … maybe CFT isn’t so mechanistically precise after all. Maybe the specifics of sensorimotor retraining and cognitive reframing are less important than the non-specific ones!

- Quality-adjusted life years (QALYS) is a fishy instrument, long “criticised on technical and ethical grounds,”19 and perhaps not the best choice for a primary outcome.20

- Kent et al. picked people they thought would do well with CFT … and excluded plenty of very real kinds of back pain patients that they did not think would do well. This is a tricky one, and not a bad one as study flaws go, but it needs a mention.21 “Back pain” includes many kinds of patients who aren’t nearly as likely to respond to CFT.

That is quite a list of possible concerns … and I left out my biggest, about the magnitude of the effects, and how that data was presented. That needs its own section.

I’ve got bad news about the good news

You already know the results were strongly promoted as “good news” — that’s why we’re gathered here today. But what good news exactly? And how good?

- A 2-point improvement in pain on a 10-point scale, from 6-ish to 4-ish.

- An 8-point improvement in disability on a 24-scale, from 14-ish to 7-ish.

- Those improvements were sustained for a year.

- The “value” (bang for buck) of care was high.

- Biofeedback as a part of therapy had no effect.

- Nothing seemed to go badly.

The durability of the improvements is probably the major thing powering the “good news” vibe.

The magnitude of the benefit? The “effect size”? Not so much. Honestly, if this study hadn’t been loudly touted as a good-news win for CFT, I don’t think I would have been inspired by the data to call it “good news” at all.

And that’s bad.

“A ~2 point reduction in NPRS and ~15 points in Roland Moris is what you will get in almost any intervention under clinical trial.”

And I’ll repeat (because it’s really important): this was not an efficacy trial! I know it’s kind of an arcane distinction, but it’s important. So-called “pragmatic” trials like this produce “smoke” evidence, not proof of “fire.” You can only nail down efficacy with especially well-controlled trials, and this was not that. To me, the strong declaration of good news reads a bit like excessively celebrating a bronze medal.

If I were the CFT folks, I’d probably be offended by this meme, unless I had an unusually good sense of humour. 🙂 I actually put quite a bit of thought into making the meme fit here. I puzzled over how to label the gold and silver podiums, because the point is not actually that CFT is inferior… just that it’s probably (based on the effect size) in roughly the same league as many other mediocre contenders, rather than an obvious winner.

An even bigger section about the small effect size

Practically anything you do for almost any kind of pain patient will tend to produce benefits in the same ballpark as RESTORE’s results. It’s true that these results are a bit more robust than the usual, and in a couple noteworthy ways … but nothing that couldn’t easily evaporate in a do-over by other scientists, or even the same ones.22

The size of the effect in this case is in the sweet spot for arguing about:

- It’s big enough to look good to proponents and optimists.

- It’s small enough to be an easy target for critics and cynics.

These extremes are reflected in the contrast between RESTORE and a more sober take on similar data crunched in a 2014 review.23

It was a little disturbing to see RESTORE’s remarkably uncritical reception from all the therapy boffins on social media … the same folks who would be screaming “foul” if this was a trial showing small effect sizes for dirty rotten passive modalities (e.g. dry needling) and more obvious quackery (e.g. ozone therapy or acupuncture). Too many people happily found good news about CFT in this study… and then stopped thinking about it. Why risk spoiling a good thing?

The authors themselves are the most keen of them all. Senior author Peter Kent:

“These large, sustained effects are unusual.”

The word “unusual” is tricksy. How unusual they are is open to interpretation. They don’t seem all that unusual to me, frankly. Maybe just a little. But I’ve been looking at effect sizes like this for my whole career and called them “underwhelming” a kajillion times.

There is no simpler way of hyping the results of a scientific study than rounding up from “okay” to “good.” It’s a small leap with a disproportionate effect on the potency of the good news. The actual effect size here is not spelled out in the abstract, and no self-respecting abstract would ever leave out an impressive effect size. I hereby invoke The Salamander’s First Law of Abstract Interpretation:

If the effect size isn’t in the abstract, it’s underwhelming.

I’ll give the last word on the effect size to Bronnie Thompson (just to emphasize that I’m not the only one thinking “meh”):

“Let’s temper the enthusiasm with some realism, OK? … Although these are statistically significant and better than ‘usual care’ (whatever that means), people with low back pain continue to have ongoing pain at 4/10 on this (stupid) numeric rating scale.”

Packaging best practices: CFT for sale

Some people really don’t want to see the work they’re already doing “packaged” and sold for profit as a treatment system. Fair or not, CFT is going to face resistance from clinicians who feel that they were already doing something a lot like CFT — and they are very wary of its commercialization. For instance, despite differences from CBT, CFT is still very CBT-ish: its critical components have been a part of cognitive-behavioural management of pain for literally decades. The same approaches that haven’t exactly solved humanity’s big back pain problem.24 Do we really need a new branded variant of that? Even if it’s truly good?

“Something promising about to be ruined by the potential for reputational gains and training sales opportunities. … ”

Phil Greenfield, Facebook comment referring to CFT

“Of course the entire shebang is being monetised as is, BS and all.”

anonymous

“Unpopular opinion: Cognitive Functional Therapy (CFT) is ‘usual care’!”

Some of this resistance is relatively generic concern about the corrupting power of the almighty dollar, but I’m also talking about more specific and vehement objections to CFT specifically, like this one from Dr. Jim Eubanks via private message (quoted with permission):

“In light of this [failure to acknowledge that CFT is very similar to existing good quality care], it’s hard not to see it ultimately as an attempt to consolidate market share for the selling of courses. … I love the ingredients of CFT, which include sound principles of good care, but I’m concerned by the salesmanship that too often accompanies MSK therapies and interventions. … I don’t think those champions of a thing in the clinic who stand to make money from its success should ever hold the keys to the definitive stance on its evidentiary success.”

Or Bronnie Thompson:

“Don’t oversell and hype what isn’t terribly technical but is hard to do. If all we learn from the RESTORE trial is that when therapists get confident to listen well, and guide discovery in movement, people begin their own journey to wellbeing, then I’m perfectly happy. Let’s just not trademark this practice. It should be fundamental to practice.”

But is CFT is actually being branded, trademarked, marketed, etc? There is a spectrum of commercialization, and some modalities never go down that road, or not far, but CFT has indeed already begun its slide down that slippery slope.

There’s now a “Cognitive Functional Therapy tiered training program.” RESTORE is being competently “monetized,” albeit modestly and idealistically: founder Peter O’Sullivan says it’s non-profit, or at least low profit. That’s good to know, but “what could possibly go wrong” still applies, and “profit” is hardly the only concern here: any revenue at all, reputation, and investment are also all very powerful forces, and it’s common for healthcare brands to be virtuous (or seem that way), entirely independent of their medical and scientific merit. So this still looks like the general kind of thing that was so cynically predicted by many people when RESTORE was published. There is a serious risk that CFT will now become just another “modality empire,” prioritizing its reputation and revenue over good clinical science.

The branding and standardization of therapy methods is nearly impossible to do without “selling out,” thanks both to perverse incentives and overwhelming social pressures in the wrong direction. Most professionals and patients easily succumb to the allure of a branded methods and the assumption that “there must be something to it”… and are largely oblivious to their corrupting power and long-term consequences. Even the best of them seem doomed to turn into dumbed-down dogma, and to produce at least one or two generations of therapists still clinging to it — because of their literal investment in it — long after science has pointed out that their emperor has no clothes.

A method of therapy can truly be a good idea, founded by people who are smart and wise … and still become a simplistic parody of itself when it goes mainstream. That’s the danger. Even if CFT is actually great. Which is far from guaranteed.

Lasting results? RESTORE 3 years later

As of the summer of 2025, The Lancet has published a three-year follow-up report that says the original benefits of CFT just kept on trucking!25 For three years! Great news? The authors obviously think so! Unsurprisingly, they are now touting CFT as “the first treatment for chronic disabling low back pain with good evidence of large, long-term (>12 months) effects on disability.”

That quote could certainly help promote CFT training.

A sustained effect of CFT suggests that instilling a self-regulatory capacity — teaching a man to fish — might be the active ingredient that makes CFT special, accounting for any durable benefit. But this new follow-up evidence has all the same caveats as the original … and it adds some new limitations, including a major one.

This is classic survivorship bias territory! What would the three-year graphs for the dropouts alone look like? And what if the long-term graphs had included a bunch of poorer data points?26

These patients all still had pain and disability after three years, and at best their improvements were just 4 points on a 24-point disability scale and 1½ on a 10-point pain scale. I wouldn’t refuse improvements like that, but I can’t get excited about them either: they don’t impress me. And those numbers would almost certainly get even less impressive if all those people who didn’t phone home after three years were counted … which they clearly should be if we care about the true average effect of CFT over time.

The RESTORE follow-up is indeed “evidence” of a lasting CFT benefit, but I don’t think it’s the “good” evidence. Without more and better trials, we’ll never know if CFT truly works for a CFT-ish reason, or any reason, for any duration.

Summing up RESTORE + CFT as of 2025 (including the follow-up)

RESTORE was an impressive attempt to standardize and test the real-world effectiveness of a cocktail of education, encouragement, movement, and lifestyle changes — a lot of ingredients that have been popular with progressive healthcare professionals for many years. But CFT didn’t perform anywhere near as well as the headlines and social media buzz suggested: not all that impressive even for disability, and certainly not for pain itself, not originally, and not after three years.

And what benefit it did detect might be attributable to artifacts and confounders, like a frustrebo effect from not getting “the good stuff.” A replication attempt seems likely to fail.

RESTORE’s results are certainly not bad news, and they are consistent with CFT being good medicine, but even results twice this good still wouldn’t have “proved” anything. Not with that study design. Without comparing CFT to other high-intensity, psychologically informed exercise programs with similar therapist contact, the specificity of even a *modest* CFT effect is just *implied* by the data, and not actually demonstrated.

It was a meaningful step on the long road to CFT becoming an evidence-based therapy — a journey I hope continues. But I fear that it might never be completed, or even continue, because BPS-ified care is just too tricky to standardize. I think it’s a lot like trying to teach people to be good teachers (almost literally).

And now CFT is a “brand,” and healthcare brands tend to be impervious to criticism and negative trial results — and therefore impervious to improvement.

I am not convinced that bad beliefs and a fear of movement is the back problem that needs solving in the first place. I worry that CFT — for all its “less wrong” virtues, despite being so much better than what it aims to replace — could be mostly barking up the wrong tree, and earning its modest benefits thanks mostly to the non-specific effects of being treated nicely and being as active as possible.

•

An abridged version of this analysis is included in PainScience.com’s huge science-based guide to back pain, which is like a compilation of twenty years worth of blog posts like this, a 200,000-word beast … but more organized than just a pile of posts. It’s written for both patients and professionals, like all my content. Read the large, free introduction.

About Paul Ingraham

I am a science writer in Vancouver, Canada. I was a Registered Massage Therapist for a decade and the assistant editor of ScienceBasedMedicine.org for several years. I’ve had many injuries as a runner and ultimate player, and I’ve been a chronic pain patient myself since 2015. Full bio. See you on Facebook or Twitter., or subscribe:

What’s new in this article?

Five updates have been logged for this article since publication (2023). All PainScience.com updates are logged to show a long term commitment to quality, accuracy, and currency. more

Like good footnotes, update logging sets PainScience.com apart from most other health websites and blogs. It’s fine print, but important fine print, in the same spirit of transparency as the editing history available for Wikipedia pages.

I log any change to articles that might be of interest to a keen reader. Complete update logging started in 2016. Prior to that, I only logged major updates for the most popular and controversial articles.

See the What’s New? page for updates to all recent site updates.

Aug 18, 2025 — Added a section about the 3-year follow-up to RESTORE claiming “lasting results.” Improved list of flaws and limitations. Most notably, added to a key footnote about the quality of shams for CFT. Other minor improvements throughout.

May — Noted that CFT training is now for sale, and adjusted the conclusion summary.

March — Added a footnote about how a CFT trial could be placebo-controlled.

2024 — Added a footnote clarifying a potentially controversial point about the nature of CFT.

2024 — Conversion from a members-only blog post to a free article in the main PainSci library, with a variety of minor adjustments.

2023 — Publication.

Notes

- Kent P, Haines T, O'Sullivan P, et al. Cognitive functional therapy with or without movement sensor biofeedback versus usual care for chronic, disabling low back pain (RESTORE): a randomised, controlled, three-arm, parallel group, phase 3, clinical trial. Lancet. 2023 May. PubMed 37146623 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 51276 ❐

Curiously, I have no idea what “RESTORE” actually means. It’s used only a few times in the paper and never actually defined. It just sounds nice?

- Meziat-Filho N, Fernandez J, Castro J. Cognitive functional therapy for chronic disabling low back pain. Lancet. 2023 May. PubMed 37146624 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 51279 ❐

- Vibe-Fersum K, O’Sullivan P, Skouen JS, Smith A, Kvåle A. Efficacy of classification-based cognitive functional therapy in patients with non-specific chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Pain. 2013 Jul;17(6):916–28. PubMed 23208945 ❐

- O'Keeffe M, O'Sullivan P, Purtill H, Bargary N, O'Sullivan K. Cognitive functional therapy compared with a group-based exercise and education intervention for chronic low back pain: a multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT). Br J Sports Med. 2020 Jul;54(13):782–789. PubMed 31630089 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 51268 ❐

- Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Sep;(9):CD000963. PubMed 25180773 ❐

Kamper et al. studied the results of a variety of trials of back pain treatment done in a way that was consistent with the biopsychosocial model of health care, a humanistic and holistic vision of care that integrates more psychological and social considerations with the more bio-centric medical model. They concluded that “multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation” was modestly effective — a bit less pain, a smidgen less disability — but also required a lot of time and resources, and was not clearly an overall win compared to more accessible treatments. It’s a damned-with-faint-praise conclusion if I ever heard one. It’s the sound of scientists saying “meh.”

- Need a reminder? The Lancet has some major bloopers in its long history, like the odious Wakefield paper linking autism to vaccines, the abominable PACE trial, or more recently a trial of Trump’s COVID drug, hydroxychloroquine. Obviously I’m not saying RESTORE is anything like those! Just pointing out that The Lancet is clearly far from infallible.

- It occurs to me that I swallowed (hook, line, sinker) the “good news” slant in the paper and the media before I actually knew for myself that it was good news because of that powerful combination of being told it was good news and wanting to believe it.

- Peter O'Sullivan directly attributes pain to over-protection: “We have all these rules around, ‘sit up straight’, ‘brace your core’, ‘lift with a straight back’, which actually teaches people to over-protect their back, stop moving it normally and start over-protecting it, and that creates pain and distress.”

- Taylor AJ, Kerry R. When Chronic Pain Is Not "Chronic Pain": Lessons From 3 Decades of Pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017 Aug;47(8):515–517. PubMed 28760092 ❐

- Ben Cormack, Peter Stilwell, Sabrina Coninx, Jo Gibson. The biopsychosocial model is lost in translation: from misrepresentation to an enactive modernization. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2022:1–16. PubMed 35645164 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 52047 ❐

This thoughtful paper argues that Engel’s biopsychosocial model (“an important framework for musculoskeletal research and practice”) has been misapplied in 3 ways:

- biomedicalization — just paying lip service to humanism & holism, but still being really rather biomedical

- fragmentation — tendency to perceive patients' complaints as this or that (e.g. bio or psycho or social), instead of this AND that (it’s always all of the above)

- neuromania — it’s ALL about the 🧠!

Result? “Suboptimal musculoskeletal care,” in the opinion of the authors.

I explore this paper and topic in much more detail in BPS-ing badly! How the biopsychosocial model fails pain patients.

- Ingraham. A Cranky Review of Dr. John Sarno’s Books & Ideas: Sarno’s methods are historically important, based on a kernel of an important truth that has been blown waaaay out of proportion. PainScience.com. 2433 words.

- “Rooted in” is informal, of course, and does not exclude other roots. CFT is also rooted in biological mechanisms for pain, and the relationship between pain and psychology is messy (understatement). But CFT has at least one fat root that is seems like an obvious “psychogenic hypothesis,” namely that fear and perception of threat can “amplify” pain, pure top-down modulation. Arguably that is even the crown jewel of CFT (and more generally of “pain neuroscience education”), name. Psychology on one side of the equation, pain on the other! If that’s not a psychogenic hypothesis, I don’t know what would qualify.

I wish these examples were imaginary, but I encounter clinical reasoning like this on a daily basis. The first two are depressing clichés in the world of therapy and rehab, and the third is an example of disturbingly real beliefs adapted from a recent conversation with a professional.

“Structuralism” is the excessive focus on causes of pain like crookedness and biomechanical problems. It’s an old and inadequate view of how pain works, but it persists because it offers comforting, marketable simplicity that is the mainstay of entire styles of therapy. For more information, see Your Back Is Not Out of Alignment: Debunking the obsession with alignment, posture, and other biomechanical bogeymen as major causes of pain.“Efficacy” is how well a treatment works in ideal circumstances, such as in a carefully contrived scientic test. Unfortunately, real life is rarely ideal! (You may have noticed.)

“Effectiveness” is how well the same thing works in the real world, in typical clinical settings and patients’ lives. Which is what matters to most patients, of course.

A trial like RESTORE cannot even show efficacy, let alone effectiveness (more below). The goal of “controlling” trials is to show that an apparent benefit is due to an “active ingredient” and not some other confounding factor — and there very many tricksy confounding factors that are forever getting underestimated, especially in the life sciences. This trial was controlled, but it was not controlled by comparison with a sham (a placebo). But without a placebo control, you just cannot show efficacy clearly. Instead, you get something analogous to “circumstantial” evidence in law — evidence that “relies on an inference to connect it to a conclusion of fact.” Indirect evidence is not necessarily wrong, but it can also easily be misleading. That “inference” step can be a doozy, especially in medical research.

You would placebo-control a CFT trial by comparing CFT to a well-designed sham protocol: something that is plausible and engaging for the patient, with plenty of therapeutic attention on them, but which lacks CFT’s defining characteristics, philosophy, and presumably active ingredients.

Comparing something with as much therapeutic interaction as CFT to boring “usual care” is extremely prone to a frustrebo effect (“performance bias”). You solve that problem by making sure the control group participants don’t think they are being deprived of “the good stuff.” Which means you have to put on a bit of a show for them! You can see that at work in every good sham, whether it’s “stage dagger” acupuncture needles or a laser therapy device that just puts out a red light, the goal is to make the sham seem as real and good as the real them, but lacking its presumed active ingredient.

A specific example: de Lira et al. made exactly the same mistake as RESTORE in their 2025 trial of CFT, a putatively “sham-controlled” trial that was so poorly chosen that it seriously undermines their positive results. The problem is that the sham was “neutral talking” plus an unplugged photobiomodulation machine. Having a clinician supervise the application of a gadget while chatting about the weather is not a good sham of CFT, and no one should be surprised that is outperformed by CFT! Of course it will be, because it doesn’t seem like “the good stuff” at all. In fact, it’s almost the opposite: treatment like that is stereotypically rote, boring physical therapy. You can’t prove that CFT works better than high-quality clinical attention by comparing it to low quality clinical attention.

- CFT was administered by 18 highly trained, fidelity-monitored clinicians, working under trial conditions, with a booster session at 26 weeks. Would we see the same results in the messy, under-resourced reality of most healthcare systems? A skeptic could suggest this is just another “boutique trial” result: a proof of concept under optimal conditions (efficacy) that will fizzle when scaled (effectiveness), like those endless stories we here about amazing new technologies that never actually make it to market because there is some serious deal-breaker trying to turn it into a product.

RESTORE doesn’t even deliver “proof” of the concept, not by a long shot. But even if it did … CFT could well still be futile in real-world conditions.

- People with serious stubborn medical problems seek out clinical trials, hopeful that they will finally get some relief. So how do you feel when you join a trial… and get stuck in the “no hope” group? You don’t feel great. And that disappointment turns up in the numbers! Performance bias isn’t some cute technicality researchers can just wave away: it’s a potent force, a classic “confounder” that has been well studied. It’s one of the major reasons why blinding/masking is a thing in medical research.

Their bias is a given here — as it often is in science, because “ain’t nobody got time for that” without some skin in the game, some passion. To do science, you have to care! And so, as always, bias is noteworthy, but it’s not necessarily a deal-breaker, and I doubt that it is here. For what it’s worth, I think these researchers truly, madly, deeply care about CFT and helping people with back pain.

Their passion is not really worth much in scientific terms, of course, but it’s polite to acknowledge it. None of this means that they aren’t sincere and compassionate. But we all have trouble thinking outside of the boxes we put ourselves in, and CFT is now a very well-defined and fancy box.

Because it might go a little beyond “passion.” This team is also undeniably in a position to profit from a positive CFT trial, financially and/or reputationally (and both matter). And that kind of bias is deeper in conflict-of-interest territory. We should be aware of that.

- Prieto L, Sacristán JA. Problems and solutions in calculating quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003 Dec;1:80. PubMed 14687421 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 51286 ❐

- Fuzzy benefits like QALYS have often been used in junkier science to obscure the lack of more concrete benefits. If you can’t show that a treatment is efficacious, you can still declare “mission accomplished” with QALYS: a weird tangentially related outcome measure that only statisticians can really understand or debate! It’s also much more subject to p-hacking — like anything that requires a bigger spreadsheet. Cryptic measurements like this aren’t always abused, and I’m not saying it was abused here, but it is a bright red flag … especially in the absence of other kinds of outcomes. It is really problematic to lean on this one too heavily, which is why I never like to see it as a primary outcome.

- Kent et al. eliminated half a thousand people from their initial candidates. They did actually include some tougher cases than we usually see in back pain studies, but they still shut out a lot of people with serious back pain. How would those people have done with CFT? Was this really a study of CFT for “back pain” … or was it a study of CFT for “people with the kind of back pain that’s easier to treat”? This is an issue to some degree with all clinical trials: you can’t study everyone, so who do you leave out? It’s not wrong to select appropriate candidates for a study — patients you hope have a better chance of responding — and in this case it probably realistically reflects how clinicians would actually decide who to do CFT with. But it is important context.

- And it’s not like that would be some kind of aberration. The one-hit-wonder-ness of so many studies is such a common and serious problem that it has been called the “replication crisis.” Many influential good-news papers have reported big effects that suddenly get all scarce when someone else looks for them. And if that can happen to some genuinely impressive results, imagine how much easier it is for more modest ones to go poof!

- Kamper et al.’s (op. cit.) review makes for quite an interesting contrast with RESTORE, because they really had quite similar results … but RESTORE has a dramatically more positive interpretation. While RESTORE is a very good bit of science work in many, many ways … I have more trust in the objectivity of Kamper et al. about BPS-ified back pain care in general than Kent et al. about CFT in particular. In other words, Kent et al. strongly presented their findings as “good news,” but I strongly doubt that a re-do of Kamper et al.’s review would change their conclusion.

- Ingraham. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Chronic Pain: The science of CBT, ACT, and other mainstream psychotherapies for chronic pain. PainScience.com. 5511 words.

- Hancock M, Smith A, O'Sullivan P, et al. Cognitive functional therapy with or without movement sensor biofeedback versus usual care for chronic, disabling low back pain (RESTORE): 3-year follow-up of a randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet Rheumatology. 2025 2025/08/12.

This three-year follow-up to the RESTORE trial (Kent et al.) reports that cognitive functional therapy (CFT) produces durable and meaningful improvements in activity limitation and modest reductions in pain for people with chronic, disabling low back pain. The effect sizes for disability at 3 years are not large, but are nevertheless notable in a field where any lasting effects are notoriously rare (RMDQ mean difference vs usual care improved by 3.5 to 4.1 points out of 24). Pain intensity benefits were smaller (1½ out of 10 at most) but statistically robust.

These results support the hypothesis that RESTORE was always intended to test: targeting maladaptive pain beliefs, fear-driven movement avoidance, and lifestyle factors might alter the trajectory of chronic pain beyond symptom suppression.

Unfortunately, the results also aren't convincing, and never can be without independent replication. “Survivorship bias” was probably a particularly major confounder here, because only 63% of the original cohort provided 3-year data (and those retained were less impaired at baseline and had better 1-year outcomes).

Other significant limitations and flaws are shared with the original trial: uncontrolled, unmasked, self-reported outcomes, modest effects, risk of bias, sensors as a confounder (and more, all explored in my original analysis).

- The authors do address this concern: they “believe” that bias is “unlikely” to have been a factor, and that one-year difference wasn’t statistically significant. But that doesn’t mean there was no meaningful difference, and a belief is just a belief. So the concern stands. It still stands quite tall, I think.