Will exercising while sore help or harm?

We get sore when we work out, a phenomenon known as post-exercise soreness, or — because there’s usually a distinctive delay before it hits — delayed-onset muscle soreness DOMS). It’s also sometimes known as “muscle fever,” a wonderfully descriptive term.

DOMS is infamously poorly understood and nearly impossible to treat, despite many beliefs to the contrary (ice baths, massage, and so on). I cover all of that elsewhere. In this post, I tackle just two popular questions:

- Should you exercise while sore? Will it do any harm?

- Can exercising while sore actually help?

“Rest” is the only thing that is guaranteed to “work” for DOMS — if you wait, you will feel better. But you can’t rest harder or better to get it over with quicker. It takes as long as it takes.

But we are impatient animals, and “working through it” is a popular way to try to get to the far side of DOMS quicker. Going back to the scene of the crime, fighting fire with fire, hair of the dog that bit you. This is sometimes called “active recovery.”

Depending on how sore you are and how hard you try, exercise may help or harm. Harm is possible and even likely at the extremes. Help is just a speculative long-shot.

Should you exercise while sore? Will it do any harm?

We usually start asking ourselves these questions in exactly the situation where they of greatest concern: when we are really quite sore and considering about doing the same workout again. That specific scenario is rarely a good idea.

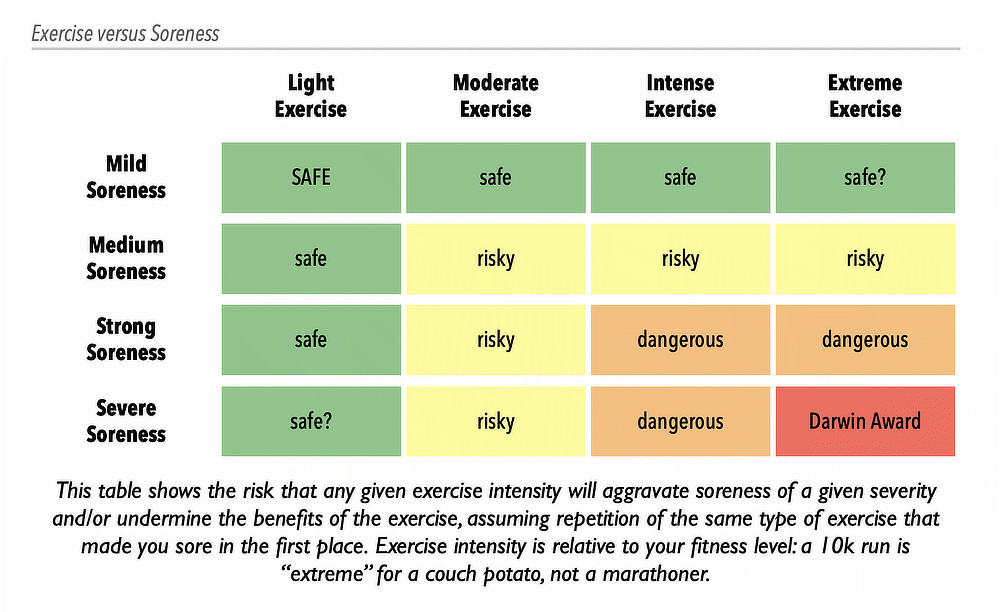

But it depends, of course. The risk is a function of both the severity of the soreness and the intensity of the exercise. Here’s a rule of thumb: your caution should increase with your soreness. But only a chart will do here:

You can overdose on literally anything, including exercise, and the more sore you are, the easier it is to overdose. Our tolerance for exercise drops while we are still recovering from the last dose.

At best, pushing through the pain is just probably harmless at lower intensities and severities. More likely, you risk no harm, but you do waste your time by sabotaging the body’s adaptive response to exercise. At worst? Serious injury is possible!

The biggest risk is “rhabdomyolysis,” a kind of poisoning from muscle trauma. Historically it was best known as a consequence of literally crushing muscles, but you can get from figuratively “crushing” your muscles too, with exercise (Knochel). It’s usually caused by manual labor, extreme endurance exercise, or lifting weights while super sore (Luetmer). It is no laughing matter, and can be dangerous (Hopkins) — or at least super unpleasant and counter-productive.

Unfortunately, knowing exactly “how much is too much” is impossible to know: it’s a moving target, dancing to the tune of many complex variables. This is the rabbit hole of what constitutes safe/optimal “recovery time,” the Holy Grail of elite athletics. Trying to do a deep dive into the science of load management this is like diving into a 3-foot deep pool: you’re going to hit bottom. There are just too many unknowns (Soligard).

Can exercising while sore actually help?

It may be safe to exercise with mild enough soreness and/or light enough exercise… but could it actually help? Is it an optimization? Can light exercise make DOMS tamer and briefer? Can it reduce the risk of other injuries?

Probably not, but no one actually knows.

Really and truly, this one is just unanswered: if it has ever been studied properly, I cannot find the science. To date, I am aware of just a single relevant study: a 2003 experiment that showed that a session of yoga modestly reduced soreness up to a day later compared to no yoga. But it’s such a small signal from a tiny study, just 24 people, that it really isn’t worth anything on its own (Boyle).

The research clearly shows that exercise relieves soreness while you are doing it, but there is just no data at all on how it changes the next day or two of soreness. Many experts assert that the pain-killing effect of exercise is temporary, but I cannot find any data that actually supports that belief one way or the other.

Read lots more about DOMS: