Does anxiety cause back pain?

Three weeks ago I had the tiniest of car accidents: I was waiting for a light, and there was a small squeal and a crunch and a bit of rocking as another car drove gently into my driver-side door. I’ve hit potholes significantly more jarring. A hockey player could easily have moved my car more than that with a good hip check. Injury was impossible.

But stress was not. Weirdly.

The other driver was a mild-mannered middle-aged guy who amiably took full responsibility. As accidents go, it could hardly have been more low-key. And yet I was surprised to find myself feeling anxious about it for days afterward, my mind cooking up weird worst-case scenarios. I don’t really get why I was worrying about this, but I was.

And I have been suffering through a flare-up of back pain ever since.

Coincidence? I think … I think …

I think I still don’t know. After all these years studying back pain, and writing my second longest book about it, I just still don’t know. I guess I need to keep writing.

Muscular hypoxia driven by stress-induced muscle clenching: still the king of popular ideas about anxiety and back pain

Many people specifically believe that stress makes us clench our muscles … and that cuts of circulation and makes them ache … and this happens more in the back and butt than anywhere else, and that is the root cause of a large percentage of back pain and sciatica … but also, of course, the shoulders, neck, and head.

Dr. John Sarno's extremely influential books are probably the main thing responsible for the popularity of the idea that stress/anxiety causes back pain.

People believe this because it comes straight from the books of the late Dr. John Sarno, which were read by millions starting in the late 80s and continuing to this day (though probably finally in decline now). He was truly famous for this claim. It is one of the most influential ideas in all of musculoskeletal medicine, and there are many modern riffs on it.

And it was almost certainly wrong in all of the particulars, and — although it’s not my goal today — I could probably convince many people that Sarno was wrong about the mechanism. But good luck convincing anyone that stress doesn't contribute to back pain. Almost everyone believes it happens somehow.

It’s just unclear exactly how. Suspiciously unclear.

Do we have more than speculation?

It has always seemed like back pain must surely be at least partially caused by anxiety, stress, depression, and other kinds of psychological distress. (I will just say “anxiety” for the rest of the post, but I will mean “all of the above” every time.) Most of us suspect that anxiety causes back pain to some degree, somehow — maybe conjuring it out of nothing, like a direct sensory amplification. Or perhaps it gets other physiology to do its dirty work, like Sarno’s “tension myositis.” Or maybe it’s mostly just good old fashioned cramping — perhaps like a tension headache.

Or maybe the relationship is even more roundabout, like the popular vicious cycle hypothesis: pain … fear … immobility … more pain … more fear… more immobility … rinse and repeat. Anxiety would be like gasoline on that fire. I have a diagram of this in my back pain book:

I made this diagram in about 2009. I still don’t know if back pain actually works like this. I can cite some science to back it up a little, but nothing remotely definitive.

I embraced the pain-aggravating power of anxiety for many years, because that belief was shared by plenty of actual experts,1 and that was good enough for this science journalist for a long time. Who the hell am I to contradict them? Plus there’s plentiful “circumstantial” evidence: indirect evidence of many kinds, a lot of clues, a whole bunch of where-there’s-smoke-there’s-fire evidence.

But then one day — not too long ago and maybe many years late — I asked a question I am really starting to regret: what’s the direct, compelling evidence that psychological distress of various kinds can fan the flames of back pain?

And I can’t find it! And I am a competent looker-upper of things. I can search PubMed like a boss. But I cannot find the good evidence that anxiety causes back pain.

What do we know for sure about back pain and anxiety? Based on good evidence, not just speculation?

As far as I can tell, the only thing we can really back up with good citations is that back pain is quite strongly linked to anxiety. They truly do go together. But a “link” is a far cry from strong evidence that distress is truly an engine of back pain misery. There are many problems with that hypothesis, starting with the fact that there are other perfectly good explanations for why they would go together. Such as?

- Anxiety-causes-back pain could just be bass ackwards! Maybe back pain causes anxiety … and that’s the whole story. Maybe back pain makes people nervous and unhappy.

- Both back pain and various kinds of psychological distress share a common origin. That is, they could both be symptoms of an even deeper root cause. Which is a bit freaky. (This possibility has probably not gotten enough air time, and I need to learn more about it and write about it.)

All the link means for sure is that anxiety and back pain tend to occur in the same people, but we don’t know why, and we specifically do not have any solid evidence showing a causal relationship in either direction: the right studies have just never been done.2

Quick summaries of some highlights from the literature on pain and anxiety

- Holmes 1952 — This ancient paper speculated about the relationship between “Life Situations, Emotions and Backache” … and it directly inspired Dr. John Sarno to write Mind Over Back Pain (1984), which became extremely influential and substantially accounts for the modern faith that stress causes back pain. From one old paper that didn't even pretend to have serious evidence of causality. Oy vey.

- Raspe 2008 — This papers asks: what if back pain was a “communicable disease”?! Meaning, what if it was caused by communication? “If information can be protective why can’t it be virulent and noxious?” They basically just looked at the dark implications of data showing that reassurance seems to help back pain patients. If that’s true, then maybe bullshit misinformation does the opposite. Interesting! But a bit dramatic and light on the evidence.

- Gerrits 2014 — Reported that anxiety and depression are more likely to develop after pain — especially pain in multiple locations. Definitely seems like a worrisome bummer!

- Gerrits 2014 — Later that year, Gerrits et al. reported something even more obvious: worse pain in more locations increases the risk of depression recurrence! But, curiously, they did not see the same with anxiety — which is a bit of a head-scratcher.

- Gerrits 2015 — We got yet more from Gerrits et cetera: a big longitudinal study of changes in anxiety, depression, and pain, concluding that they are “reciprocally linked.” That is, they tend to wax and wane together, and pain is worse in people with the most depression and anxiety. When anxiety backed off, pain improved but remained “significantly higher than healthy controls.” The study “largely confirms synchrony of change between depression, anxiety and pain.” They specifically talk about the possibility of a vicious cycle. This paper does not prove a causal relationship, but it probably comes closer than any other single citation can.

- Burke 2015 — Maybe people with pain are anxious about the pain itself — not life in general. That’s what this meta-analysis reported. People with pain are anxious, but they’re not just “anxious people.” Their confidence in performing activities despite pain (self-efficacy) was not “intrinsically tied to the chronic pain experience.”

- Stubbs 2016 — This study showed that back pain is robustly associated with mental health issues — just a good clear correlation. It doesn’t show causality, but contributes some dose-response data to the case for causality. (Causality is more likely when more cause produces more effect. But they could still both be amped up by something else.)

- Cremers 2021 — This paper over-interpreted moderator/mediator analysis of cross-sectional data, “concluding” what such data cannot actually support: that fearful misconceptions increase back-pain-related disability, and more so with greater symptoms of depression or anxiety.

Causality is tricky

Somewhat infamously, it has never been technically “proven” that smoking causes cancer — a shortcoming exploited for many years by the tobacco industry’s PR thugs, the original “merchants of doubt.” That smoking does indeed cause cancer has been established not through technically rigorous data, like a mathematical proof, but through the weight of many kinds of imperfect evidence.

Oddly enough, this is always how it goes with causality: it’s nearly impossible to be 100% sure of it, especially in messy fields like the life sciences. If you want proof of causality, stick to physics! There are lots of complex causal relationships we cannot “prove,” or just haven’t bothered to, but … meh, close enough! Such examples are like puzzles with a few missing pieces: we can still tell what the picture is.

There are three major things you must suss out to know if one thing truly causes another:

- Correlation — The correlation that is so famously not, in itself, evidence of causation. But this is all we can get from 95% of the back pain and anxiety research. (Even correlations can be hard to find if there’s a long delay, which is one of the big problems of epidemiology.)

- Time ordered — The cause precedes the effect in time. This can only be established by the right kind of research, and it tends to be expensive and difficult to do, and so we get very little of it — hardly at all in the case of most topics in musculoskeletal and pain medicine.

- Non-spuriousness — The appearance of causation can’t be a fluke or have some other sneaky explanation. But other explanations can be very sneaky indeed. It’s hard to prove a negative, and there are a lot of “unknown unknowns” in medicine. In the case of back pain and anxiety, the appearance of anxiety causing back pain could be spurious because of that possible deeper cause for both back pain and anxiety.

We have lots of the first major kind of evidence, almost none of the second, and at least one big reason to think the correlation might be spurious.3 So a score of about 1.1 out of 3.

The hypothesis that anxiety causes back pain is in scientific limbo. But humans hate knowledge limbo. We would rather be confidently wrong than uncertain.

But it smells like causality!

Which is just another way of saying Meaning there’s just an awful lot of clues that feel like they add up to an almost-obvious casual relationship.

Famously, correlation is not causation, but “it sure is a hint” (Tufte), and we take that hint: most of us accept that the correlation between pain and anxiety is probably not a coincidence. We reckon that they correlate because they have some kind of casual relationship. Probably a messy one — direct and indirect, probably a little of one way and some of the other way — but definitely causal somehow.

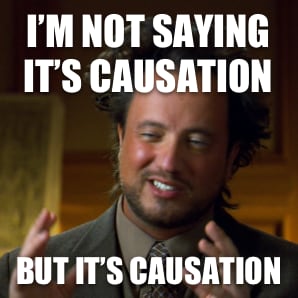

That assumption is both plausible and wildly popular. It is made by patients, clinicians, and researchers alike. Many scientific papers strongly imply that these things do indeed cause each other without saying it directly, and without supporting data.4

But we need to remember that it’s just an assumption.

There’s really a LOT of this going on when it comes to the role of the mind in pain. Including from many people who should know better.

Maybe let’s not blame psychology for back pain when we have no way of knowing if it’s really true

It is reasonable to speculate that there is a casual relationship? In an academic way, sure. We can get dorky about it and chase the truth. But we’re also talking about real people in pain, and in that context…

Dear professionals: Please do not tell patients with back pain that their mental state is responsible for their pain when you cannot possibly know that.

Dear patients: If a professional (or a book) seems to be convincingly blaming your pain on your psychology, please know that they cannot possibly know that.

We might know someday. We do not know yet.

Considering buying the PainSci guide to low back pain, which is like a compilation of twenty years worth of blog posts like this, a 200,000-word beast … but more organized than just a pile of posts. It’s written for both patients and professionals, like all my content. Read the large, free introduction.

Notes

- Turns out that there are also some credible experts that do not agree that back pain is significantly driven by psychological distress by any mechanism. It’s not like there were never any dissenting voices… they just mostly weren’t voices I was hearing in my social media “echo chamber” these last few years. A hazard I have been slowly growing wise to.

- All we do have is a lot of cross-sectional data — slice of time data — about risk factors. And note that “risk factors” are not “causes”! A risk factor is something that is known to co-exist with a bad outcome. Many risk factors do not actually cause the bad outcome: they merely tend to occur in the vicinity of bad outcomes, usually because they share underlying causes. You see a lot of conflation of “risk factors” with “casual relationship,” because “risk factors” just sounds like it must be causal — but in fact a risk factor is closer to an uninterpretable correlation.

- There are much more detailed criteria, like the famous Hill’s criteria for causation. In 1965, Dr. Bradford Hill, an English epidemiologist, proposed nine requirements for causality: strength, consistency, specificity, temporality, biological gradient, plausibility, coherence, experiment, and analogy. A tenth often proposed by others is “reversibility”: when you take away the cause, the effect should also go poof.

- For instance, Cremers et al specifically mention that their data cannot show causality… but then they wave that limitation away and get to work speculating about causality! “I’m not saying it’s causation, but …” They *should* have been deterred by that limitation, but they weren’t. This is so common it’s almost standard, so it’s no wonder everyone is confused about this: the evidence that we are supposed to base medicine upon is not just thin, but over-interpreted by scientists themselves.