A Bizarre Case of Mouth Pain (Member Post)

Today I have a story for you from my own experience with a strange and nasty mouth pain … and it’s surprisingly obvious explanation … and the easy solution.

Strange, nasty pains aren’t normally so tractable! This is a genuinely intriguing and happy treatment success story. It is of particular interest to massage therapists, and to anyone who has ever had a “strange and nasty pain.”

So that probably means you. It means most people. Although the cure part is quite unusual, I think an awful lot of people have had the same kind of problem I had.

I will begin the story for all readers today — a substantial free introduction — but the “reveal” will be for members only. This is the first members only post in quite a while, and it’s also a re-run, although just barely: it’s about 3× more post than the original, which was the very first members-only post I ever did, back in 2021. But most members haven’t seen the original, and no one has seen it like this — with much more discussion, especially of a certain room elephant. 🐘 I have always wanted to return to this story to try to make more sense of my experience, and now I have.

Blog posting has been a bit thin lately due to a family emergency. A month ago, my wife slipped on ice, injuring her back quite badly — and, sigh, not for the first time. Injuries multiply!1 Hopefully things will soon be getting back to normal at the Salamander’s World HQ. Meanwhile, thanks for your patience and patronage, PainSci members — this is exactly when your financial support of a small business matters the most!

The setup: ominous maybe-Covid throat soreness

My wife and I were binging the last season of the show “Vikings” — a good show in many ways, but now all tangled up with pandemic memories. It was the spring of 2021, peak pandemic, so naturally that throat weirdness made me worry that I might be getting my first case of Covid.2

(Heads up: this post is quite rich in chatty footnotes. I digress a lot.)

I was even more suspicious because I’d been in a crowded restaurant for the first time since pre-pandemic, only a couple days before — just enough time for incubation (although, interestingly, incubation can be much slower3). So I went to bed with the Covid fear clinging to me like a stink.

But the Covid fear didn’t last the night.

I finally got the Covid in the summer of 2023, and it started with a sore throat much like the one this story is about — which turned out to be something else entirely.

The weirding: from sore throat to sore face

The symptom grew and changed fast, like a xenomorph — a great analogy, but only if you know what in hell a xenomorph is.4 Soon after my head hit the pillow, it started to become more of a sore mouth, dominating the right side of my soft palate. And that didn’t seem much like any cold/flu I’d ever had.

Every time I started to drift off, painful swallowing jolted me awake. I took some ibuprofen at 1AM, which did nothing. By 3AM the pain had spread to my teeth, jaw, and cheek on that side, and the fear of Covid was replaced by fear of … what? A jaw infection? Soft palate cancer? I was in that dark place where so many chronic pains have begun, thinking: What could possibly cause THAT pain?

My own chronic pain story (since 2015), has featured a kaleidoscopic variety of aches and pains — so much that the variety is like a symptom unto itself. So I’m used to disconcerting sensations, but this was one of the worst on record: fast, fierce, and bizarre.

By morning I was an exhausted, nervous wreck. My soft palate felt like it had been punched. The whole right side of my face throbbed, and I couldn’t move my jaw properly. I was freaked out. As the sun rose, it was time, finally, to take a peak into my pie hole. What was going on in there?

The surprising explanation and solution

I might have saved my night if I’d looked sooner. When I finally got a flashlight and took a look, I was quite startled by what I found in my mouth:

- The problem couldn’t have been more obvious if there’d been a little devil with a pitchfork in there. There was a blatant, unmistakable, holy-crap-look-at-that, “well there’s you’re problem” sign. Objective evidence of what was wrong. Nothing was bleeding or inflamed. There was no foreign object. But it was still obvious.

- And it was a sign that suggested an easy fix! Which actually worked. The pain was gone less than a minute later. And it didn’t come back.

And … that is the end of the free introduction to this members-only post. Sorry for the cliff-hanger.

PainSci members are finding out what the hell was in there right now, but the post stops for everyone else right here. Join to unlock the rest of the story.

Pause, cancel, or switch plans at any time. Payment data handled safely by Stripe.com. More about security & privacy. PainScience.com is a small publisher in Vancouver, Canada, since 2001. 🇨🇦

The salamander’s domain is for people who are serious about this subject matter. If you are serious — mostly professionals, of course, but many keen patients also sign-up — please support this kind of user-friendly, science-centric journalism.

So that’s where I cut off non-members — a real cliff-hanger! But members get to find out right now…

So what on Earth did I see in my dang mouth?!

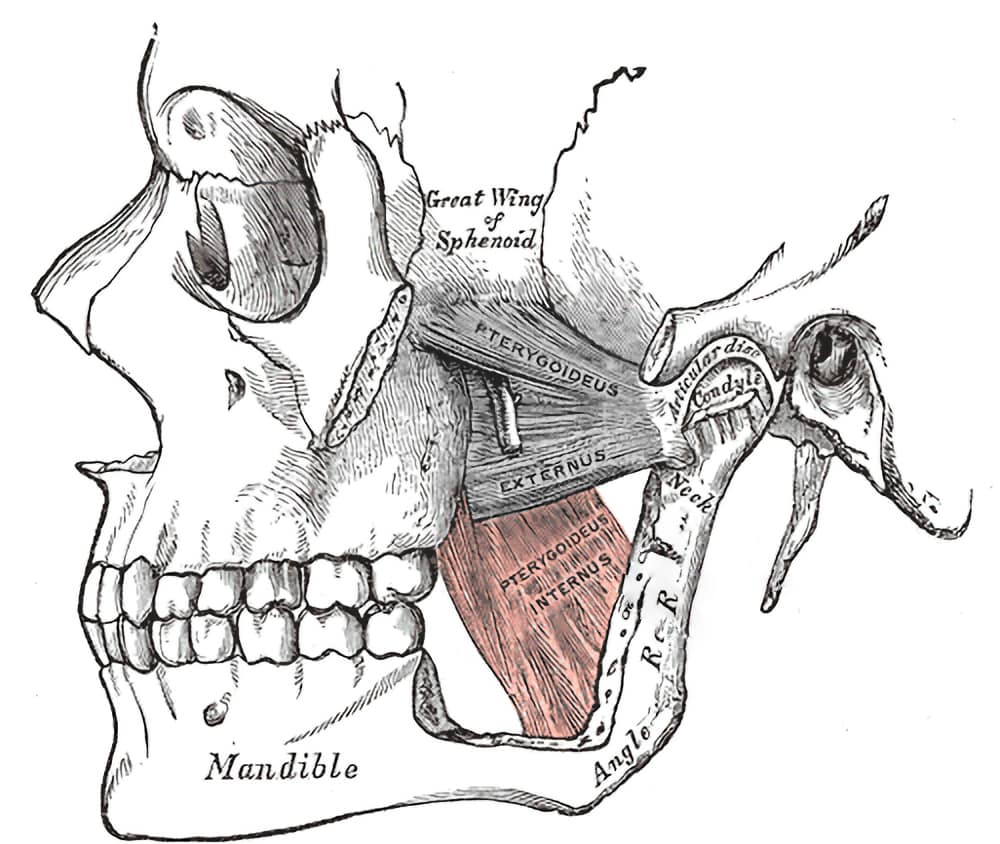

I saw … my right medial pterygoid muscle. It was standing out in sharp relief. The medial pterygoid is much like the masseter muscle, but smaller and on the inside of the temporomandibular joint, instead of the outside. You can see where it is normally — under the mucosa behind the molars — but you cannot normally see the muscle itself, bulging conspicuously.

Mine was impossible not to see: a hard cord standing well out from the normal contours of the area, as obvious as flexed biceps. It looked thoroughly different from the other side, which was an easy comparison.

It looked obviously contracted. It was cramping — and presumably it had been cramping like that all night. Cramping is an all-too familiar problem for me, which made me even more confident about what I was seeing. But I think that this would have looked like a cramp to anyone who can point to the pterygoid.

My first thought: cause or symptom? Maybe it was just cramping as a reaction to something else! Seeing the state it was in was certainly surprising and intriguing, but not instantly reassuring. Such problems usually can’t be resolved in a minute, which is why what happened next was even more surprising.

The pterygoid muscle is a tricky one to visualize from a 2-dimensional diagram. The way the head is wrapped around this one, you really need a model to wrap your head around it. But the simple way to think of it is that it’s just an “internal masseter.”

Rubbing it out

I reached in with an index finger and gave my pterygoid a gentle poke. It felt like a taught rubber band — but painful. That slight pressure made my soft palate light up with the same pain that had been driving me nuts all night. The pain also spread — less dramatically — to the teeth, jaw, and cheek.

Interestingly, I had never once been conscious of pain at the location of the muscle itself — only the “referred” pain.5

I rubbed the poor thing cautiously for about 30 seconds. And I must have magic hands, because that gave me immediate and great relief, as obviously helpful as stretching out a cramping calf muscle. It visibly softened as I worked, fading into the mucosa like Homer simpson backing into the hedge.

The cramp was gone. The pain was gone. They did not come back. That was simply the end of the ordeal — like I’d flipped a switch.

Some initial reactions to this odd experience

- How common are less severe and obvious examples of this kind of thing? How often do we suffer from strange aches and pains that are just some damn little muscle cramping, but we just can’t see it, or reach it? More generally, how many pains have relatively simple but invisible causes, making them seem mysterious? I suspect this it’s extremely common.

- The proximate cause of this pain appeared to be badly behaved muscle tissue. It is unclear why the muscle was in that state. There could be any number of deeper explanations, some of them quite ominous (e.g. neuropathy). But the tissue that actually hurt certainly seemed to be muscle. And muscle can certainly be a source of pain, although that is an oddly controversial point.6

- The cramp was clearly not a response to any continuing, significant provocation … or it would have come back. It was self-sustaining. Regardless of what got it going in the first place, it had become its own clinically significant phenomenon, capable of continuing to cause trouble all by itself. Like the Ship of Theseus paradox, the pain was both some original problem and a new one.

- This story is a win for massage. There was so little massage it barely even qualifies; it was so effective that it almost seemed like cheating. But I think “massage” still deserves the credit: what put a stop to the pain was definitely applying pressure to soft tissue. Brief but powerful. I’ve been brewing a “less is more” point about massage for quite a while now: I think surprisingly small doses of massage can be helpful, and this is a great example.

And now for the tricky one, that elephant in the room …

“Trigger points” have entered the chat

I don’t know if this is a story about a “trigger point” or not — and I mean that, I truly do not know. Maybe I shouldn’t even care! But the resemblance is so obvious that it would be weird not to talk about it.

Quick review: Trigger points are the common name given to unexplained sore spots in muscle, and it’s a controversial idea.7 But the conventional wisdom about trigger points is that they are “micro cramps.” Which is an awful lot like what I saw!

More specifically, my terrible pterygoid may have been a fine example of the infamous “taught band” reputed to house many trigger points.

Also, the decisive relief from only a bit of rubbing harmonizes nicely with a widely held belief that “fresh” trigger points are easier to ease.

My anecdote sure sounds like a trigger point anecdote.

The fallibility of anecdotes about trigger points

Or maybe that’s all nonsense! Maybe this was clearly more of a “macro cramp” — the whole muscle, not just the “taut band.” And maybe the treatment wasn’t a “trigger point release,” but just gentle stretch of a spasm, no more exotic than stretching out your foot when it cramps. Is there a need to speak of trigger points, other than noting the resemblance? Maybe not.

Many would argue that “anecdotes” are all that trigger points have ever had, and most of them are extremely unreliable. But not all anecdotes are created equal, and most people telling stories about trigger points aren’t particularly skeptical about them.8 But I am.

I’ve had my own strong doubts about trigger point therapy since near the end of my career in massage therapy in 2010.9

So let me take you much further back in time, all the way to 1997, in my first year of my massage therapy training …

*flashback harp*

A “toothache” that was actually probably a trigger point maybe

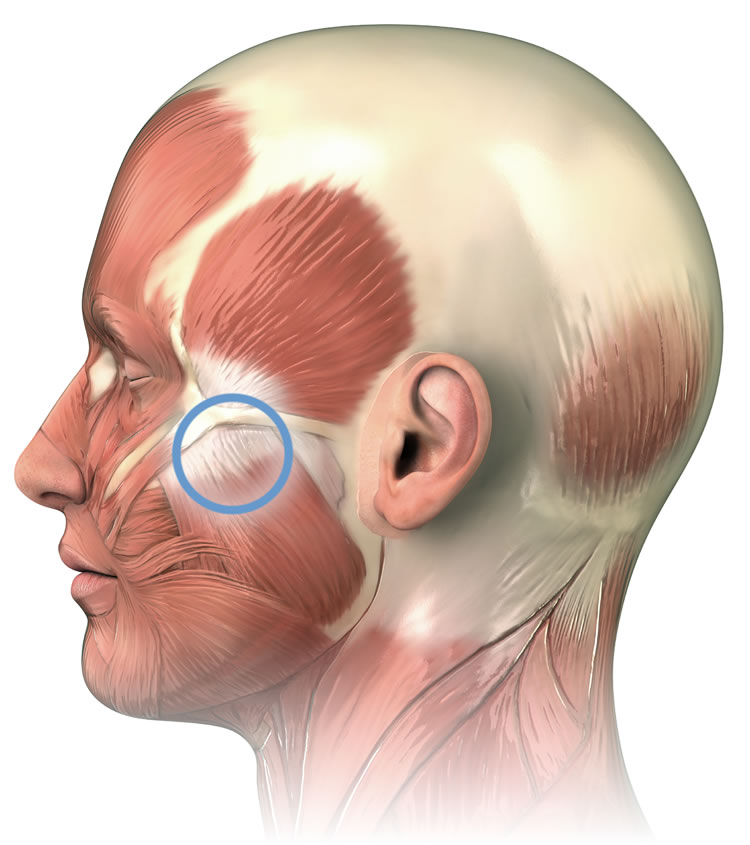

My tooth had been throbbing for days, and I had a dentist appointment the next day, where I expected a diagnosis of “rotting tooth.” But first? By sheer chance, I had a massage therapy appointment first … and my massage therapist fixed my toothache completely, just by briefly rubbing my jaw muscle.

The spot she found in my masseter muscle was exquisitely sensitive. Pushing it made my tooth light up with pain like it was an LED. It was the damndest thing! That “reproduces the pain” thing can be an amazing sensory phenomenon. But it was gone after just a little rubbing — more than my pterygoid took, but really not very long, a few minutes at most.

And quite gentle, I should add. (Again, “less is often more” with massage.)

I cancelled my dental appointment, and that tooth never ached again. Wow, right?

That experience was my original inspiration for embracing trigger point therapy early in my career, and that therapist was a mentor to me for a few years.

But then I slowly became a hardened skeptic, keen to question my own “reality,” and I began to doubt my own best anecdote. It couldn’t possibly have been as miraculous as it seemed at the time! Maybe I missed an alternative explanation that I wouldn’t miss these days. Or maybe it was just a fluke.

And so that 1997 anecdote, once one of the pillars of my career, eventually faded into a dubious legend, that I didn’t take seriously, even though it was my very own success story.

The masseter muscle descends from the cheekbone to the back, bottom edge of the jaw. I don’t clearly remember exactly where the toothache-causing spot was, but — based on lots of clinical experience since then — there’s a good chance it was in “the notch” under the zygomatic arch, which is a classic “perfect spot” for massage. But it could have been anywhere in that muscle.

Where’s your skepticism now, pal?

The credibility of that old mouth-pain story seems partially restored by my much fresher one. It may have really meant what it seemed to mean to me originally.

Many years into my identity as a curmudgeonly skeptic, my mind is armed with a full suite of critical analysis tools that I didn’t even know existed in 1997 — thinking critically is truly a skill that takes time to learn. There are a great many ways to explain how ineffective treatments can seem to work.10 But none of that seems to be helpful here.

I certainly can’t just dismiss what happened on either occasion as a coincidence: it was too sudden and dramatic in both cases. You can’t “regress to the mean” in a the few second or minutes it takes to rub an obviously spasming muscle. I was nowhere close to a “darkest before dawn” effect.11

There were no “non-specific effects of the therapeutic encounter” to blame it on in 2021, no relevant “contextual effects.”12 There might well have been some “therapy theatre” in the 1997 experience, but not in 2021 — and yet they both had the same outcome.13

Perhaps I benefitted from an optimism-powered placebo? Ha! The sight of that cramping muscle made me miserable and alarmed, not reassured and optimistic — and I didn’t feel happier for at least an hour, because I thought it was all too likely to come back! I was only retroactively confident about it. (Not that placebo is anywhere near as potent for pain as reputed in the first place.14)

Nothing I have ever used to explain these experiences to myself is particularly implausible or absurd, certainly not compared to the worst ideas in this business.15

The informal fallacy of “post hoc ergo propter hoc” is like catnip for the human mind (and maybe the canine mind as well). We are absurdly keen on inferring causation from simple B-follows-A correlations. But as often as humans are wrong to infer causality just because one thing followed another … causes do, in fact, precede their effects! It’s not an informal fallacy to assume, for instance, that you got an electric shock because you stuck a fork in a power socket. Read more.

It’s not a coincidence that I decided to re-run this post in early 2025

Every once in a while the topic of trigger points blows up on social media again, and it did again in late February 2025, triggered by a new paper by Chad Cook et al.16

The paper takes the idea of myofascial pain syndrome (“too many trigger points”) seriously, which annoys skeptics. But it also impugns the scientific credibility of trigger points, which upsets the believers. You know it’s a good compromise when no one is happy.17

I didn’t participate in this kerfuffle. I am sick of the low quality of the “debate.”18 I had a very “I’m getting too old for this shit” reaction to the debate this time. Not today, Satan! Maybe another time.

So what am I taking away from this experience?

I’m not fool enough to think that I “know” what happened, but my confidence level is fairly high: although I don’t know why I had a pterygoid cramp like that, it seems clear that I did. And it obviously behaved much like I think “trigger points” behave — based on my deep knowledge of the lore and literature.

On the other hand, I also don’t think it’s obviously necessary or useful to invoke “trigger points.” I could just as happily call it a weird little cramp.

But that may be a distinction without a difference, since “weird little cramp” is, after all, basically the main hypothesis for what a trigger point actually is. It has always been clear to me that “trigger points” is just an over-interpreted label for that clinical phenomenon. I don’t much care what we call it, but I care about understanding it, and the trigger point “model” probably isn’t accurate, but it might be useful.

In any case, I strongly suspect that various kinds of cramping account for a lot of otherwise unexplained aches and pains. The direct evidence for this broad hypothesis is weak at best, virtually nonexistent at worst. But the indirect and partial evidence is extensive, and the plausibility is high … and my pterygoid terrorism was a superb example.

•

This post is now a big new chapter in my trigger points e-book — like it wasn’t big enough already. It’s an exhaustive exploration of the topic, all with my weird agnostic approach. Like all my books, it’s for both patients and pros, and it’s a “forever” book that gets updated slowly but steadily over the years, and customers always have access to the current version.

Notes

She was in a nasty accident in Laos in 2010, which crushed a vertebra (among other things). Although she recovered surprisingly well from that (a case study in resilience), she has had escalating pain and scoliosis ever since (a case study in long-term consequences of injury). Unfortunately, she fell more or less right on on that old fracture site, and the pain was … big. Rehab is going poorly so far, many struggles. Our sleep has been severely disrupted.

I told this story in a bit more detail on Facebook [Facebook].

I had just been vaccinated a few weeks earlier, but even then I knew to expect “breakthrough” cases. It was a terrible term: the vaccines were always built to blunt the symptoms, not to stop infection, a distinction that never really got through to most people. I also knew the protection of vaccination was strong but not perfect, and the threat of Covid has always been significantly greater than influenza even for the fully vaccinated. It’s an intimidating infection even when it doesn’t maim and kill.

For instance, my wife — getting a lot of mentions in this post! — had a case of COVID two years later, in 2023 … which caused a hair-trigger cough that has never gone away, still a thing in early 2025. It’s not full-blown long Covid, but it’s some kind of lasting damage. She may have a Covid-caused cough for the rest of her life — and also a vulnerability to all future respiratory tract infections. That is not “minor”! And even in 2021, it was clear that Covid was dangerous even for the vaccinated.

- Fun fact: viral incubation periods can be shockingly long. According to Lauer et al, the mean for Covid is five days, and almost everyone shows symptoms within ten days, but the longest confirmed incubation period is fourteen friggin’ days! Many times someone has told me they can’t possibly have Covid, or be at risk, because “it’s been more than a week since I was exposed to it” … and I have to decide whether or not to be that guy and crush their naive optimism with facts. Rarely worth it.

This is an absurd aside, a very different kind of footnote about incubation periods…

“Xenomorph” [Wikipedia] is the “formal” term for the alien monster in the Alien franchise of movies, which has always been sloppy with the details of how quickly the alien monster develops. In the original 1979 classic, the alien incubates for at least a couple days in John Hurt’s chest before the famous dinner scene when it bursts through his ribs … and then the weasel-sized larva grows into a huge adult over another few days. It’s fast, but maybe possible for exotic biology.

But in the more recent films, alien development is accelerated to the point of physics-defying nonsense. For instance, in 2024’s Alien: Romulus, the foot-long baby alien grows into a 10-foot monster faster than you can boil an egg. It’s just silly.

So that is what I mean when I say that my symptom grew and changed “like a xenomorph” — a fast and radical transformation.

- The brain is somewhat inept at precisely locating internal pain and so sometimes we experience pain in a broad area around or near the cause, or even further afield. This is the same phenomenon as heart attack pain felt mainly in the arm: the brain just can’t figure out where the pain is coming from, and the arm pain is a bad “guess.” Patterns of referral from the musculoskeletal system are somewhat predictable, and most referred pain spreads away from the centre and the head (laterally, distally). By contrast, visceral referral is much more erratic.

- Graven-Nielsen T, Mense S, Arendt-Nielsen L. Painful and non-painful pressure sensations from human skeletal muscle. Experimental Brain Research. 2004 Dec;159(3):273–83. PubMed 15480607 ❐

This study attempted to determine if painful and non-painful pressure sensations from muscles actually exist. That may seem like an odd research question to ask, but it is possible that much of what seems like “deep” muscle sensation could in fact come an illusion of depth inferred from pressure on the skin, like a “3D” image projected on a flat screen. Sensation and perception are full of oddities like this, so we cannot actually take it for granted that muscle itself is sensitive.

The authors put it this way: “Painful and non-painful pressure sensations from muscle are generally accepted to exist but the peripheral neural correlate has not been clarified.”

This is a challenging question to study, because it’s difficult to eliminate skin sensation as a factor! So these researchers went to rather a lot of trouble to do just that, with “anaesthetised skin combined with a block of large diameter muscle afferents.” And it turns out that people can still feel pressure and pain even with anaesthetized skin. Although not conclusive in itself, this evidence does strongly suggest that muscle tissue proper knows when it’s being poked!

- No one doubts that people do have weird sore spots that need explaining, but the explanations — and solutions — are hotly debated. Skeptics don’t think they are a “thing,” not a palpable or treatable “lesion” in muscle tissue. 1000 × more information here.

- Skeptics are supposed to sneer at all “anecdotal evidence” or “anecdata” equally, even though obviously there’s actually a great range of quality and value. There is a world of difference between some brainwashed grifter telling stories about the supplement their pyramid scheme is built on, versus a self-aware expert thoughtfully reporting their experience and exploring different possible interpretations, including “no idea.”

I was a Registered Massage Therapist with a busy practice in Vancouver, Canada, from 2000–2010. I quit the profession in disgust before I could be “fired” for being critical of pseudoscience and alternative medicine. I changed my professional focus to science journalism and anti-quackery activism, writing mostly about massage-adjacent topics in the early years, but then spreading out into anything relevant to any kind of chronic pain or injury rehab — an effectively infinite list of topics. See my bio.

The profession of massage therapy, alas, is rotten with myths and bullshit. If that statement gets your back up, or if it paralyzes you with professional angst because you agree with it — please read this short article: Reassurance for Massage Therapists: How ethical, progressive, science-respecting massage therapists can thrive in a profession badly polluted with nonsense.

- Ingraham. The Power of Barking: Correlation, causation, and how we decide what treatments work: A silly metaphor for a serious point about the confounding power of coincidental and inevitable healing, and why we struggle to interpret our own recovery experiences. PainScience.com. 2393 words.

- That’s where we finally start to enjoy natural recovery right just as we get desperate enough to seek treatment, a really common way for bogus therapies to get the credit for healing.

- Contextual effects are the effects of the context in which treatment happens, the messy halo of variables that surround and influence it. Coincidentally, this is the subject of my last small blog post, actually.

Therapy theatre is therapy that is optimized for contextual effects with an emotionally engaging narrative about what’s actually going on. The most pure examples of therapy theatre are faith healing, and healing rituals in a folk medicine context. The theatrics are not generally deceptive or misleading, but well-intentioned exaggerations of partial truths. In manual therapy, sensory input is often a critical part of the show, using strong and novel sensations to “demonstrate” the power of the treatment.

In the context of trigger point therapy, the seed of truth is that pressure on specific spots certainly can cause strong and interesting sensations, but it gets theatrical when therapists start to explain. The theatrical version tells a story of wisdom in finding the spot, it’s clinical significance, and the power in being able to manipulate it — most of which is speculative at best, and some of it is often just self-aggrandizing garbage, e.g. “I’ve seen people recover from an ulcer after treating a trigger point like this. Just sayin’.” A non-theatrical version would simply tell no story at all, no magic hands to be amazed by.

- Placebo is fascinating, but its “power” isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, even for relief of purely subjective symptoms like pain: the power of belief is strictly limited and accounts for only a little of what we think of as “the” placebo effect, which is actually a collection of diverse nonspecific effects and research artifacts. For more information, see Placebo Power Hype: The placebo effect is fascinating, but its “power” isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

- There are many examples of ideas that are much more implausible, but I’ll highlight the most blatantly obvious one: acupuncture points are way more implausible than trigger points. Acupuncture points (and meridians) are quite literally “magical,” requiring a childish, pseudo-religious faith in a life force unknown to physics. They certainly have a superficial resemblance to “trigger” points, nestled inside their “taught bands” just like acupuncture points are embedded in meridians … but the resemblance ends there. The idea of trigger points as a “micro cramp,” or any other kind of lesion, even if it’s dead wrong, is at least a coherent and testable hypothesis about physiology and pathology. In terms of scientific plausibility, they aren’t even in the same league.

- Cook CE, Degenhardt B, Chiro SAB, et al. Myofascial Pain Syndromes: Controversies and Suggestions for Improving Diagnosis and Treatment. JOSPT Open. 2025;(ja):1–13.

- Ironically, Cook et al. took an approach that is similar to my own — relatively agnostic, aiming for a balance where both sides are taken seriously. But somehow I’ve mostly managed to make everyone happy instead of no one! Skeptics cheerfully cite my work, assuming that I am on Team Skeptic … but many trigger point therapists also lay claim to my allegiance! The truth is that I’m a dirty rotten fence sitter. I guess people see what they want to see.

- It’s badly polarized, everyone picked their “team” years ago, and discussions are dominated by the militant. Simple rhetorical bloopers are made *ad nauseam* by people who should have known better all along. And meanwhile I’ve already written down everything I have to say on the topic: hundreds of thousands of words, no stone unturned, every detail of the topic examined earnestly.