The Mind Game in Low Back Pain

How back pain is powered by fear and loathing, and greatly helped by rational confidence

One of my chronic low back pain patients reported that he’d had a brief relapse after a hard fall on his tailbone. He was playing hockey and got slew footed (tripped). Over the course of the evening, his back seized up into a nasty imitation of previous episodes. Fortunately, by the next morning he had recovered — a testament to his progress.

Many people with back pain are essentially living in that over-reactive, seized-up state — their back reacts to just about everything like that. What was a temporary setback for my client is a continuous reality for someone who has a more serious chronic low back problem. Either that, or they have a “hair trigger” back that may be fine most days, but gets set off by nearly any provocation.

Two key underestimated factors in low back pain

There are two key differences between someone whose back reacts to everything like this, and someone who only reacts to more serious stresses and also recovers more quickly:

- The number and severity of muscular trigger points in the region.

- The confidence of the victim that they are not really fragile and that there is nothing serious wrong.

Time and time again, it is the people who buy into the idea that their back is structurally unsound who get a case of “fraidy cat back” and react to every challenging stimulus as though it were a lumbar emergency — they fear and loathe their own backs.1 It is likely that, to some extent, pain can be a learned behaviour, and the twitchiness of many back pain patients is a related phenomenon.2

It is those who have some confidence that their spine is basically a sturdy structure who are relatively immune to stressful incidents.3

It can take an enormous amount of de-programming to convince people that their backs aren’t actually fragile, disaster-prone structures. Mental habits are incredibly strong, and all the more so under stress. When we are in pain, we are likely to revert to the most familiar thought patterns. This is why I place such a strong emphasis on the “mind game” in low back pain treatment. It’s not that back pain is “all in your head” — it’s not; there absolutely is pain in your back — but it is very much affected by what’s in your head.

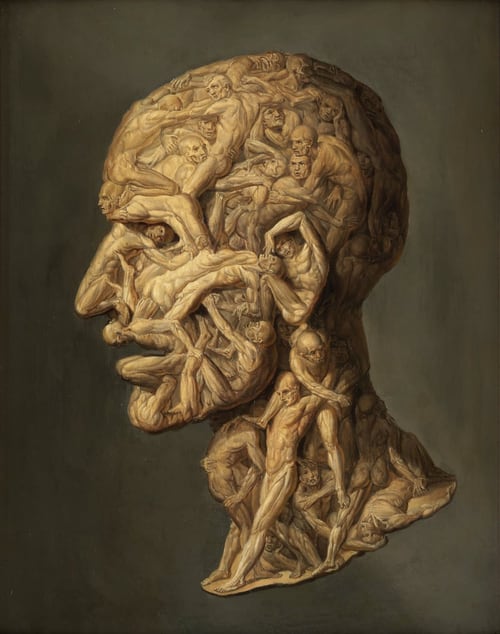

Model of doom and gloom

Lumbar spine models like this almost all show a herniated disc. Some go a step further and show discs slipped so far they’ve completely left the spine!

Here’s pain researcher Lorimer Moseley making this point in a great TED talk. He’s talking about how pain is always worsened when you believe that there is danger … and plastic models of slipped discs are much too persuasive.

Any piece of credible evidence that they are in danger should change their pain … And they are all walking into a hospital department with models like this on the desk: what does your brain say when it sees a disc that’s slipped so far out it’s sitting on its own? If you’ve ever seen a disc in a cadaver, you can’t slip the suckers — they’re immobile, you can’t slip a disc — but that’s our language, and it messes with your brain. It cannot not mess with your brain.

Lorimer Moseley, from his surprisingly funny TED talk, Why Things Hurt

14:33

Don’t miss that video. So good.

Greg House on false positives

It is almost impossible emotionally to see anything that looks “bad” on an X-ray or MRI and not worry about it. It’s also almost impossible to get a reliable MRI report4 or a completely healthy-looking scan of anyone. TV’s Dr. Greg House has commented on this …

House: Give him a whole body scan.

Cameron: You hate whole body scans.

House: Because they’re useless. You could probably scan every one of us and find five different doodads that look like cancer.

House, Season 1, Episode 17, Role Model, written by Matt Whitten

Or low back pain. And yet most visible defects are clinical red herrings, about as worrisome as a birthmark, and signify nothing at all except the power of modern medical technology to scare you silly if you aren’t armed to the teeth with confident knowledge to the contrary.

I provide numerous examples from the scientific literature elsewhere, but one of the best examples is the most personal: my wife suffered an extraordinary fracture of her spine, and has a lot of titanium and unevenly healed bone in her back today … but minimal back pain. If you can be more or less pain free with that going on your back, you can rest assured that a little joint degeneration is not the cause of severe back pain.

The science has your back

Time and time again, the most respected medical experts in low back pain have emphasized the importance of psychological factors in low back pain, instead of the scary-looking things that show up on scans.

For instance, consider the case of Dr. Nikolai Bogduk, a mainstream physician, a man who is much more inclined to criticize a fringe theory than to champion one: and yet Dr. Bogduk believes that the most important thing a health care professional can do to stop acute back pain from becoming chronic is to “treat the patient nice and convincing him that there is nothing so horribly wrong.”5

In 2009, the American Pain Society published new guidelines for low back pain interventions, and their first recommendation — top of the list — was that “rehabilitation emphasizing cognitive-behavioral approaches should be considered”6 — and “cognitive-behavioral approaches” is basically doctor talk for “treat the patient nice and convince him that there is nothing so horribly wrong.”

Low back pain is not all in your head … but it is affected by your head

The mind game in low back pain is so important not because it’s a psychosomatic condition, but because the psychological element is a powerful lever. The mind game is a way to break vicious cycles — just as it has the power to negatively influence back pain, what you think and feel also has the power to help back pain.

You are much likelier to feel better if you know that:

- there is no structural problem (or no serious one)

- the “bark” of low back pain is almost invariably worse than its “bite”

- you probably won’t need surgery

- stress is a root cause of low back pain and affects it, but doesn’t have to be “eliminated” (which is unrealistic) but can be mitigated

- you probably don’t have to give up playing tennis (or squash, or golf, or whatever it may be)

Tip of the low back pain iceberg!

This has been a brief introduction — the tip of an iceberg — to a central idea in low back pain therapy. There is a great deal more to learn. Most back pain patients can’t begin to really assimilate and make use of this perspective without much more persuasion. You need a mountain of persuasive evidence. That mountain of evidence exists in the form of my extremely detailed low back pain tutorial. One of the only criticisms I’ve ever received about this tutorial was, “It’s overwhelming. It’s overkill. You had me in the first few sections.” I can live with that criticism!

About Paul Ingraham

I am a science writer in Vancouver, Canada. I was a Registered Massage Therapist for a decade and the assistant editor of ScienceBasedMedicine.org for several years. I’ve had many injuries as a runner and ultimate player, and I’ve been a chronic pain patient myself since 2015. Full bio. See you on Facebook or Twitter., or subscribe:

More articles about back pain

- Neuropathies Are Overdiagnosed — Our cultural fear of neuropathy, and a story about nerve pain that wasn’t

- Don’t Worry About Lifting Technique — The importance of “lift with your legs, not your back” to prevent back pain and injury has been exaggerated

- Chronic Low Back Pain Is Not So Chronic — The prognosis for chronic low back pain is better than you think

- The Tyranny of Yoga and Meditation — Do you really need to try them? How much do they matter for recovery from conditions like low back pain?

- 6 Main Causes of Morning Back Pain — Why is back pain worst first thing in the morning, and what can you do about it?

- Back Pain & Trigger Points — A quick introduction to the role of trigger points and massage therapy in back pain

- MRI and X-Ray Often Worse than Useless for Back Pain — Medical guidelines “strongly” discourage the use of MRI and X-ray in diagnosing low back pain, because they produce so many false alarms

- When to Worry About Low Back Pain — And when not to! What’s bark and what’s bite? Checklists and red flags for the scary causes of back pain

- Your Back Is Not Out of Alignment — Debunking the obsession with alignment, posture, and other biomechanical bogeymen as major causes of pain

Notes

- Zusman M. Belief reinforcement: one reason why costs for low back pain have not decreased. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2013;6:197–204. PubMed 23717046 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 54554 ❐

Why is back pain still a huge problem? Maybe this: “It is extremely difficult to alter the potentially disabling belief among the lay public that low back pain has a structural mechanical cause. An important reason for this is that this belief continues to be regularly reinforced by the conditions of care of a range of ‘hands-on’ providers, for whom idiosyncratic variations of that view are fundamental to their professional existence.”

Well said. If only I could edit it, though, I would say that it is difficult to alter that belief in anyone, patient or professional. The belief isn’t just reinforced by the practices of manual therapists, it’s the reason for them.

- Can chronic pain be a “learned response” (classical conditioning) to things that shouldn’t hurt, like Pavlov’s dogs salivating to the ring of a bell? It’s an interesting idea, with obviously optimistic implications, because what is learned might also be un-learned. If so, it’s a bit of a brain hack, a clever and surprising solution around one of the hardest problems there is. It’s a bit unlikely, but so interesting that it’s worth discussing and exploring. See Chronic Pain as a Conditioned Behaviour: If pain can be learned, perhaps it can be unlearned.

- Vibe-Fersum K, O’Sullivan P, Skouen JS, Smith A, Kvåle A. Efficacy of classification-based cognitive functional therapy in patients with non-specific chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Pain. 2013 Jul;17(6):916–28. PubMed 23208945 ❐

The big idea of classification-based cognitive functional therapy (CB-CFT or just CFT) is that most back pain has nothing to do with scary spinal problems and so the cycle of pain and disability can be broken by easing patient fears and anxieties. For this study, CFT was tried with 62 patients and compared to 59 who were treated with manual therapy and exercise. The CFT group did better: a 13-point boost on a 100-point disability scale, and 3 points on a 10-point pain scale. As the authors put it for BodyInMind.org, “Disabling back pain can change for the better with a different narrative and coping strategies.” These results aren’t proof that the confidence cure works, but they are genuinely promising.

- Herzog R, Elgort DR, Flanders AE, Moley PJ. Variability in diagnostic error rates of 10 MRI centers performing lumbar spine MRI examinations on the same patient within a 3-week period. Spine J. 2016 Nov. PubMed 27867079 ❐

In this study, one patient with sciatica was sent for ten MRIs, which produced 49 distinct “findings,” 16 of them unique, none of which occurred in all ten reports. On average, each radiologist made about a dozen errors, seeing one or two things that weren’t there and missing about ten things that were. Yikes. Read a more detailed and informal description of this study.

- Jackson M. Pain: The science and culture of why we hurt. Trade paperback ed. Random House; 2003. p. 120–1.

Although [Nikolai] Bogduk has a reputation for having all the answers and being a bit of a ‘needle jockey’ who travels everywhere with his little vial of painkilling bivucaine, his presentation in Vienna surprised his colleagues. Instead of talking up the latest surgical intervention, he spoke about addressing the patients’ fears and anxieties, and ‘getting inside their heads.’ He emphasized that what was most important was to first eliminate ‘red-flag conditions’ that might be (but probably weren’t) causing the back pain, and then to reassure the patient that the back would most probably get better and not worse. He still believed in judicious painkilling, but what was more important in treating back pain, he had found, was communication and reassurance. Preventing acute [back] pain from turning into chronic pain was often a matter of ‘treating the patient nice and convincing him that there is nothing so horribly wrong.’

- Chou R, Loeser JD, Owens DK, et al. Interventional therapies, surgery, and interdisciplinary rehabilitation for low back pain: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society. Spine. 2009 May;34(10):1066–1077. PubMed 19363457 ❐ PainSci Bibliography 55429 ❐

This is a particularly exhaustive and useful review of back pain treatments, by the American Pain Society. They looked at 161 good studies, all randomized and controlled trials, picked from 3348 candidates. They came up with eight recommendations, such as emphasizing cognitive-behavioral approaches, and avoiding a bunch of historically popular interventions (including provocative discography, facet joint corticosteroid injection, prolotherapy, intradiscal corticosteroid injection, or vertebral disc replacement). For patients with persistent radiculopathy (sciatica), the APS recommends considering epidural steroid injection, surgery, and spinal cord stimulation.