Should you exercise when you’re still sore from the last workout?

We get sore when we work out, as you may have noticed. This phenomenon is known as post-exercise soreness, or — because there’s usually a distinctive delay before it hits — delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS). It’s also sometimes known as “muscle fever,” a wonderfully descriptive term.

DOMS is infamously poorly understood and nearly impossible to treat, despite many beliefs to the contrary (ice baths, massage, and so on). I cover all of that in a detailed DOMS guide. In this post, I tackle just two popular questions:

- Will exercising while sore do any harm?

- Or will it maybe even help?

“Rest” is the only thing that is guaranteed to “work” for DOMS — if you wait, you will feel better. But you can’t rest harder or better to get it over with quicker. It takes as long as it takes.

Unless it doesn’t. Maybe more exercise is medicine. We are impatient animals, and “working through it” is a popular way to try to get to the far side of DOMS quicker. Going back to the scene of the crime, fighting fire with fire, hair of the dog that bit you. This is sometimes called “active recovery.”1

Depending on how sore you are and how hard you try, exercise may help or harm. Harm is absolutely possible: usually just more soreness, but it can be disturbingly severe in rare cases. As for whether it can help? It is possible, but it’s mostly a speculative long-shot.

Will exercising while sore do any harm?

We usually start asking ourselves this question in exactly the situation where it is of greatest concern: when we are really quite sore and considering doing another workout. That specific scenario is rarely a good idea.

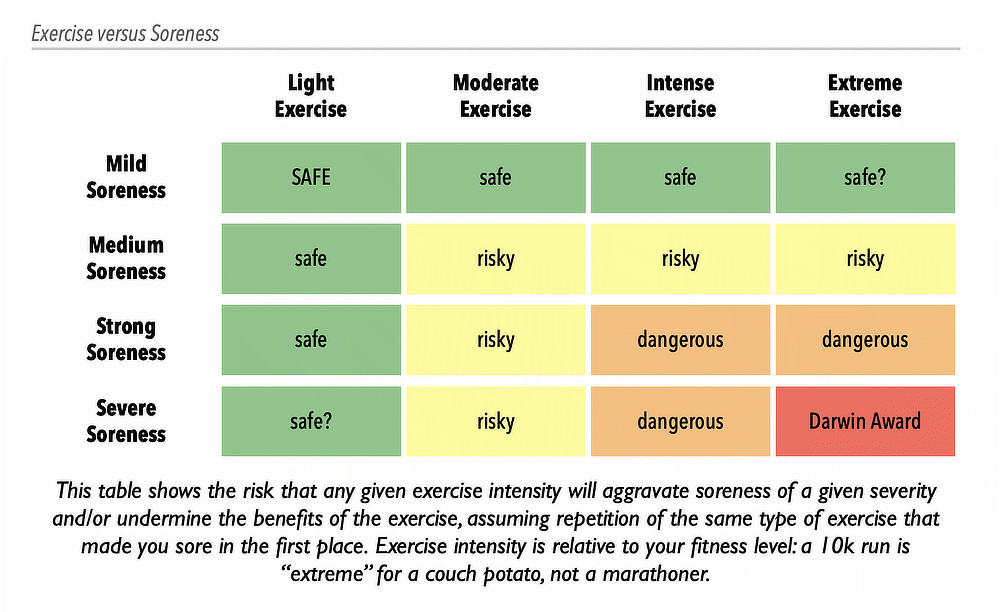

But it depends, of course. The risk is a function of both the severity of the soreness and the intensity of the exercise. Here’s a rule of thumb: your caution should increase with your soreness. But only a chart will do here:

You can overdose on literally anything, including exercise. The more sore you are, the easier it is to overdose. Our tolerance for exercise drops while we are in recovery from the last dose.

At best, pushing through the pain is just probably harmless at lower intensities and severities. More likely, you risk no harm, but you do waste your time by sabotaging the body’s adaptive response to exercise. At worst? Serious injury is possible!

The greatest risk is rhabdo

Rhabdomyolysis is a kind of poisoning from muscle trauma.

Historically, rhabdo was best known as a consequence of literally crushing muscles. But you can get rhabdo from figuratively “crushing” your muscles too, with the metabolic stress of intense exercise.2 It’s usually caused by manual labor, extreme endurance exercise … or lifting weights when already extremely sore.3

Rhabdo is no laughing matter, and can be quite dangerous4 — but milder versions are probably fairly common, and very unpleasant and counter-productive. People in this state don’t just feel extremely sore, but also gross. In the context of exercise recovery, people often interpret these symptoms positively — a badge of pride, an indicator of progress — but it’s truly not.

That is the feeling of your kidneys struggling to function properly!

Unfortunately, knowing exactly “how much is too much” is impossible to know: it’s a moving target, dancing to the tune of many complex variables. This is the rabbit hole of what constitutes safe/optimal “recovery time,” the Holy Grail of elite athletics. Trying to do a deep dive into the science of load management is like diving into a 3-foot deep pool: you’re going to hit the bottom. There are just too many unknowns.5

Can exercising while sore actually help?

Moderate active recovery may be safe … but can it actually help? Is it a fitness optimization? Can light exercise make DOMS tamer and briefer, enhancing your recovery? Can it reduce the risk of other injuries?

Probably not. But no one really knows, because active recovery is much less studied than hangover cures! It’s one those widely held beliefs that exists in a near perfect scientific vacuum. There are a few trials in the context of recovery from elite team sports like football (soccer) that are fairly relevant, but they aren’t anywhere near enough to truly answer the question … and they are are discouraging. Querido et al in 2022:6

…the effects of exercise in the recovery of physical, physiological, and perceptive outcomes have been reported as not significant,which is in agreement with the findings of the present study.

(And it’s not like Querido et al. had unreasonably high standards: they endorsed two other recovery methods despite mediocre evidence of efficacy.7)

I know of just one relevant study outside the context of professional sports: a 2003 experiment that showed that a session of yoga modestly reduced soreness up to a day later compared to no yoga. But it’s such a small signal from a tiny study, just 24 people, that it really isn’t worth anything on its own.8

The research clearly shows that exercise relieves soreness while you are doing it, but there is very little data on how it changes the next day or two of soreness. Many experts assert that the pain-killing effect of exercise is temporary, but I cannot find any data that actually supports that belief one way or the other.

What is the effect of chronic pain and illness on active recovery?

The effect of exercise on people with chronic pain is much more complicated.9 DOMS is often exaggerated in this population — more easily triggered, worse, with slower recovery — and that makes recovery trickier and riskier. But it’s still the same challenge in principle.

But many people may struggle with a truly different, dysfunctional responses to exercise: “exercise intolerance” involves physiologically wonky consequences, probably in addition to exaggerated DOMS. Famously, just advancing more carefully does not solve this problem.10 For these patients, all bets are off, all rules of thumb are on probation, and considerable caution is advisable. It is still possible that load management basically works the same way with some cases exercise intolerance (albeit with a much lower threshold and worse consequences for training errors). But it’s also possible that it is doomed to failure — as you’d expect from trying to exercise while sick.

Notes

- Confusingly, “active recovery” also refers to lighter exercise between bursts of really intense exertion (high-intensity interval exercise). Although not settled science, the evidence on that may lean towards passive recovery (see Perrier-Melo et al.) — just catch your breath, that’s it.

- Knochel JP. Catastrophic medical events with exhaustive exercise: "white collar rhabdomyolysis". Kidney International. 1990 Oct;38(4):709–19. PubMed 2232508 ❐

- Luetmer MT, Boettcher BJ, Franco JM, et al. Exertional Rhabdomyolysis: A Retrospective Population-based Study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2020 03;52(3):608–615. PubMed 31652234 ❐

- Hopkins BS, Li D, Svet M, Kesavabhotla K, Dahdaleh NS. CrossFit and rhabdomyolysis: A case series of 11 patients presenting at a single academic institution. J Sci Med Sport. 2019 Jul;22(7):758–762. PubMed 30846355 ❐

- Soligard T, Schwellnus M, Alonso JM, et al. How much is too much? (Part 1) International Olympic Committee consensus statement on load in sport and risk of injury. Br J Sports Med. 2016 Sep;50(17):1030–41. PubMed 27535989 ❐

This is the first of a pair of papers (with Schwellnus) about the risks of athletic training and competition intensity (load). Is load a risk for injury and illness? How much is too much? Is too little a problem? These papers were prepared by a panel of experts for the International Olympic Committee, and both them use many words to say the same things formally — but they are good points. Here they are in plain English:

- There’s not enough research, surprise surprise, and what we do know is mostly from limited data about a few specific sports. But there’s enough to be confident that “load management” overall is definitely important.

- Both illness and injury seem to have a similar relationship to load — lots of overlap.

- Too much and not enough load probably increase the risk of both injury and illness. You want to be in the goldilocks zone! But the devil is in the details …

- Not everyone is vulnerable to high load, and elite athletes are the most notable exception: they are relatively immune to the risks of overload, probably because of genetic gifts. Everyone else gets weeded out!

- Big load changes — dialing intensity up or down too fast — are much bigger risks than absolute load. If you methodically work your way up to a high load, it may even be protective.

- “Load” can also refer to non-sport stressors and “internal” loads, which are legion. Psychology, for instance, probably does matter: anything from daily hassles to major emotional challenges, as well as stresses related to sport itself.

- Querido SM, Radaelli R, Brito J, Vaz JR, Freitas SR. Analysis of Recovery Methods' Efficacy Applied up to 72 Hours Postmatch in Professional Football: A Systematic Review With Graded Recommendations. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2022 Sep;17(9):1326–1342. PubMed 35961644 ❐

- What methods? Massage and cold water immersion. Both of these are currently damned with faint praise by a bunch of “promising” trials that mostly aren’t very good quality, and have yet to smacked down by better trials. Ideas can persist in this semi-justified “promising” state practically forever.

- Boyle CA, Sayers SP, Jensen BE, Headley SA, Manos TM. The effects of yoga training and a single bout of yoga on delayed onset muscle soreness in the lower extremity. J Strength Cond Res. 2004 Nov;18(4):723–9. PubMed 15574074 ❐

- Nijs J, Kosek E, Van Oosterwijck J, Meeus M. Dysfunctional endogenous analgesia during exercise in patients with chronic pain: to exercise or not to exercise? Pain Physician. 2012 Jul;15(3 Suppl):ES205–13. PubMed 22786458 ❐

Exercise is great medicine for many chronic pain conditions, but there is an important “but”: it’s unclear if it’s a Band-Aid or if it actually “has positive effects on the processes involved in chronic pain (e.g. central pain modulation).” This narrative review concludes that it’s complicated and it depends, and some patients definitely have a “dysfunctional response” to exercise, and thus “exercise therapy should be individually tailored with emphasis on prevention of symptom flares.”

- www.nytimes.com [Internet]. Rehmeyer J, Tuller D. Getting It Wrong on Chronic Fatigue Syndrome; 2021 November 18 [cited 23 Aug 30]. PainSci Bibliography 52219 ❐

The huge but notoriously flawed PACE trial seemed to support the idea that chronic fatigue syndrome patients are just de-conditioned and therefore need to suck it up and exercise, slowly building themselves back up again. This was evidence-based medicine at its very worst: one low quality but influential study drowning out both contradictory evidence and patient voices. It has become the most extreme example of telling sick people that their illness is “all in your head.” Julie Rehmeyer and David Tuller’s NYT piece is the canonical summary of the whole debacle.